After just over a year at the helm, Global Fishing Watch CEO, Tony Long, reflects on how a freely accessible and near real-time digital map of the global ocean is exposing illegal fishing and changing the rules of the game, and calls on all governments to contribute data and join the movement for universal transparency.

Chasing poachers

In April this year, after an incredible three-week trans-Indian Ocean chase involving Sea Shepherd and INTERPOL, the Indonesian navy intercepted F/V STS-50, a notorious fugitive toothfish poacher recently escaped from detention in Maputo Bay, Mozambique.

This was an impressive operation demonstrating new levels of collaboration between governmental, non-governmental and international organisations in the fight against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Yet this sort of operation is expensive, not always successful, and not easily replicable at the scale needed to eliminate IUU fishing globally.

As an experienced naval officer and surveillance expert, I believe that the resources required to apprehend vessels in this way are a good investment but only when they are used to target and bring to justice the very worst offenders.

Beyond national jurisdiction, the high seas are vast, remote and lawless. Policing nearly half the surface of the globe is an impossible challenge, and illegal fishers find it easy to cross borders, unload stolen goods in port, and slip away over the horizon and out of sight.

An insidious scandal

Accounting for one-in-five fish, IUU fishing produces seafood worth up to $23.5 billion each year, and poor enforcement, lack of science-based management and inadequate global governance reduce global fisheries production by $83 billion annually.

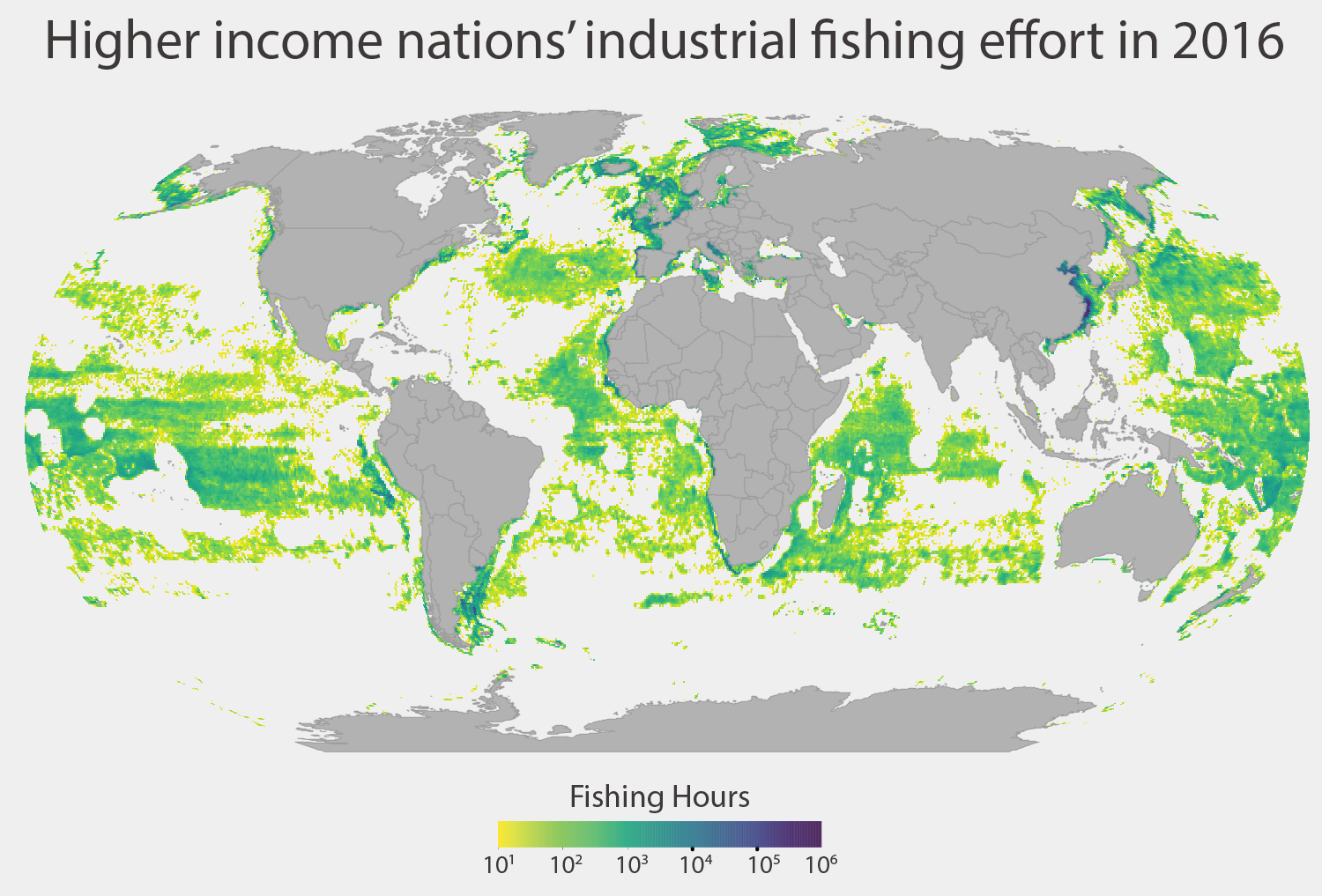

The numbers are big but belie the insidiousness of the scandal. Largely unseen, a handful of wealthy nations are over-exploiting a vital and valuable resource on an industrial scale, and the food security of 3.2 billion people who depend on fish for protein is at stake, not to mention the livelihoods of millions of artisanal coastal fishers.

IUU fishing is a highly profitable multi-billion-dollar organized crime that robs poorer countries of rich natural resources, undermines the sector’s social license to operate and deceives us all.

Changing the rules of the game

Rather than physically chasing every pirate fisher across the ocean, we need to play smart.

At Global Fishing Watch, our proposition is a simple one – through transparency, reward compliance rather than trying to police the impossible.

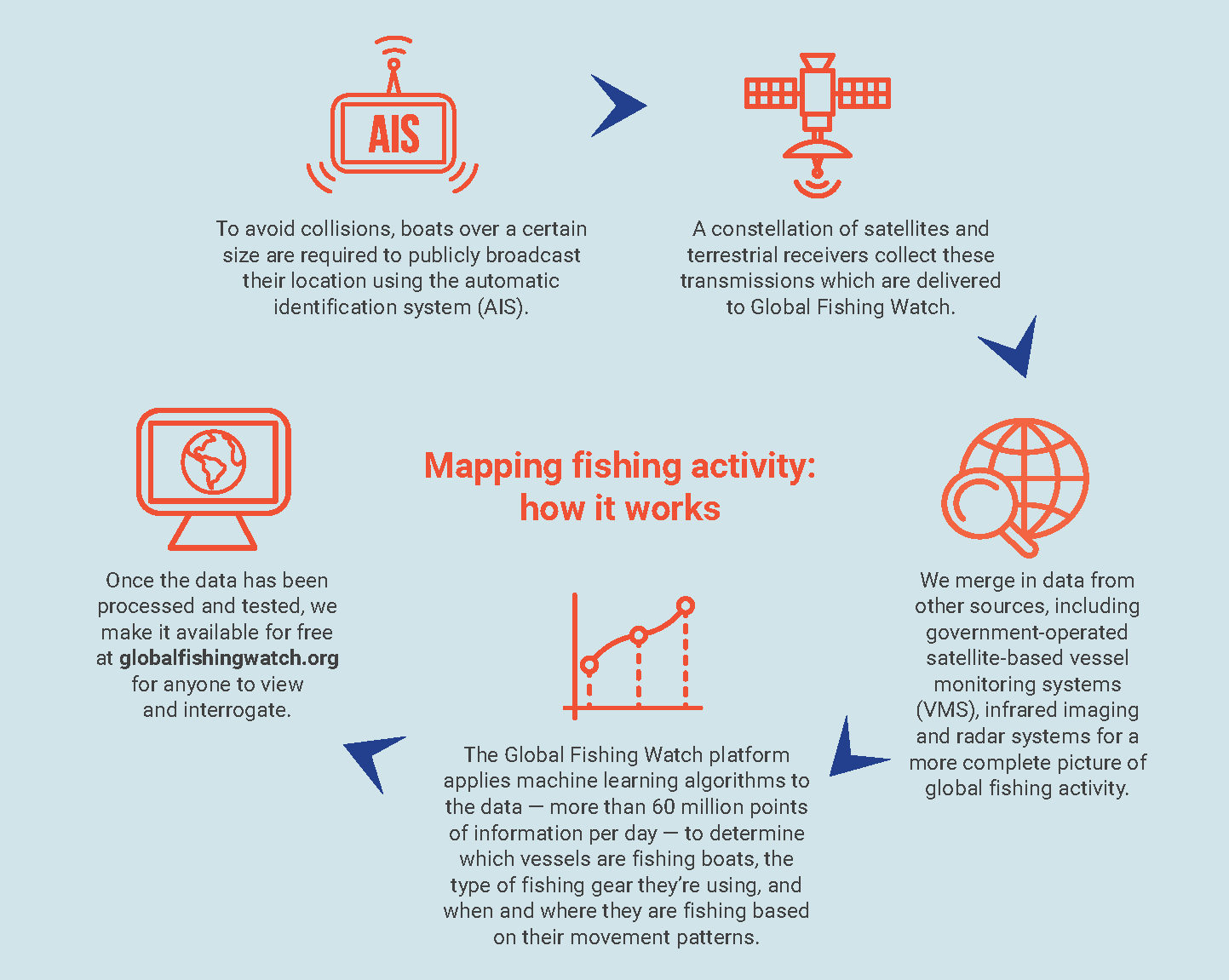

Our platform applies machine learning to vessel data – more than 60 million points of information per day – to determine which vessels are fishing, when and where, and what gear they’re using, allowing us to flag suspicious activity.

Anyone with an internet connection can use our freely available map to track more than 65,000 fishing vessels and download data about past and present activities, unlocking unprecedented opportunities to improve fisheries science and management.

And within the next ten years, we aim to track all large-scale fishing – some 300,000 boats responsible for about three-quarters of the global marine catch – and increase our ability to track small-scale fishing vessels.

Thanks to new technology powered by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, our ability to detect and track fishing activity globally continues to undergo an extraordinary transformation, putting us within reach of a real-time digital ocean and universal transparency.

If we get it right, it will revolutionize both understanding and governance of our blue planet.

Life in the fast lane

Transparency can help ports rapidly understand a vessel’s activity and could reward compliant vessels by creating a ‘fast lane’ that offers swift landings and minimal delays. And vessels with patchy tracking data, or that have gone ‘dark’ by turning off tracking devices, could be quickly identified and prioritized for further inspection.

As an individual, if you travel and try to enter a country without the right papers, you don’t get in. Fishing vessels should be no different.

Putting the burden of proof on fishers to demonstrate good practice and compliance, rather than on a country to prove illegality, is an easier and more cost-effective way to monitor fishing activity and protected areas than on-water policing, especially for countries with limited resources.

And if countries publicly share fishing vessel monitoring data, we can create a more complete picture of global fishing activity from which governments, fishers, retailers, communities and consumers all stand to gain.

Becoming a player

SDG 14 calls for the sustainable management of resources, an end to IUU fishing and harmful subsidies, science-based fisheries management and conservation of at least 10% of the world’s coastal and marine areas by 2020.

Alongside, negotiations for a new high seas treaty have begun, and the prospect of a ‘new deal for nature’ in 2020, create an unmissable opportunity for ocean stewardship and improved fisheries management that could tame the ‘wild west’ of the high seas.

By pushing the boundaries of transparency and accountability, incentivizing good stewardship, and exposing those taking advantage of poor governance, Global Fishing Watch is uniquely placed to help governments deliver sustainability, bridging the gap between our collective ambition and reality on the water.

And in this mission, 2018 has been a significant and transformational year for us. Building on and further developing our digital ocean platform, we’ve also become an influential global player, engaging the highest levels of government and driving change.

Through ground-breaking research, cutting edge technology and agile partnerships, we are building momentum for a paradigm shift in ocean stewardship that will see transparency becoming the new global norm.

To boldly go

Our priority remains making our map and data as powerful and useful as possible so that it becomes the ‘go-to’ platform for surveying and understanding global fishing activity.

In June 2017, Indonesia became the first country to openly publish its proprietary Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) tracking data via Global Fishing Watch. This instantly put 5,000 smaller commercial fishing vessels that don’t use Automatic Identification System (AIS) anti-collision system – the original foundation of our platform – on our map.

More importantly, it set a vital precedent, and in October this year, Peru followed suit, also making its proprietary data public. And Costa Rica, Panama and Namibia have now all committed in principle to publish their VMS data on our platform.

Our ambition that in total 20 country partners make their data public over the next four years, creating an unstoppable movement toward universal transparency.

A light in the dark

This year, working with partners like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), we’ve also introduced two powerful new data layers: a Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) layer that allows us to detect the lights of brightly-lit vessels and thus spot vessels not sharing their position by AIS or VMS; and an ‘encounters layer’ which provides a very good indication of where likely at-sea trans-shipment exchange of catch, fuel, stores or people are taking place.

We then plan to add data on refrigerated cargo ships involved in trans-shipment of tuna and layers that help integrate fishing activity with data on physical oceanography, biodiversity and human stressors, such as coastal population.

Breaking new ground

Putting this new flow of data to use, probing the complex challenges, and generating new evidence and insight through our Research Partners program is at the heart of our mission to improve fisheries management and ocean stewardship.

And this year, we’ve supported some of the world’s leading marine science institutes to publish over a dozen ground-breaking peer-reviewed research papers in as many months.

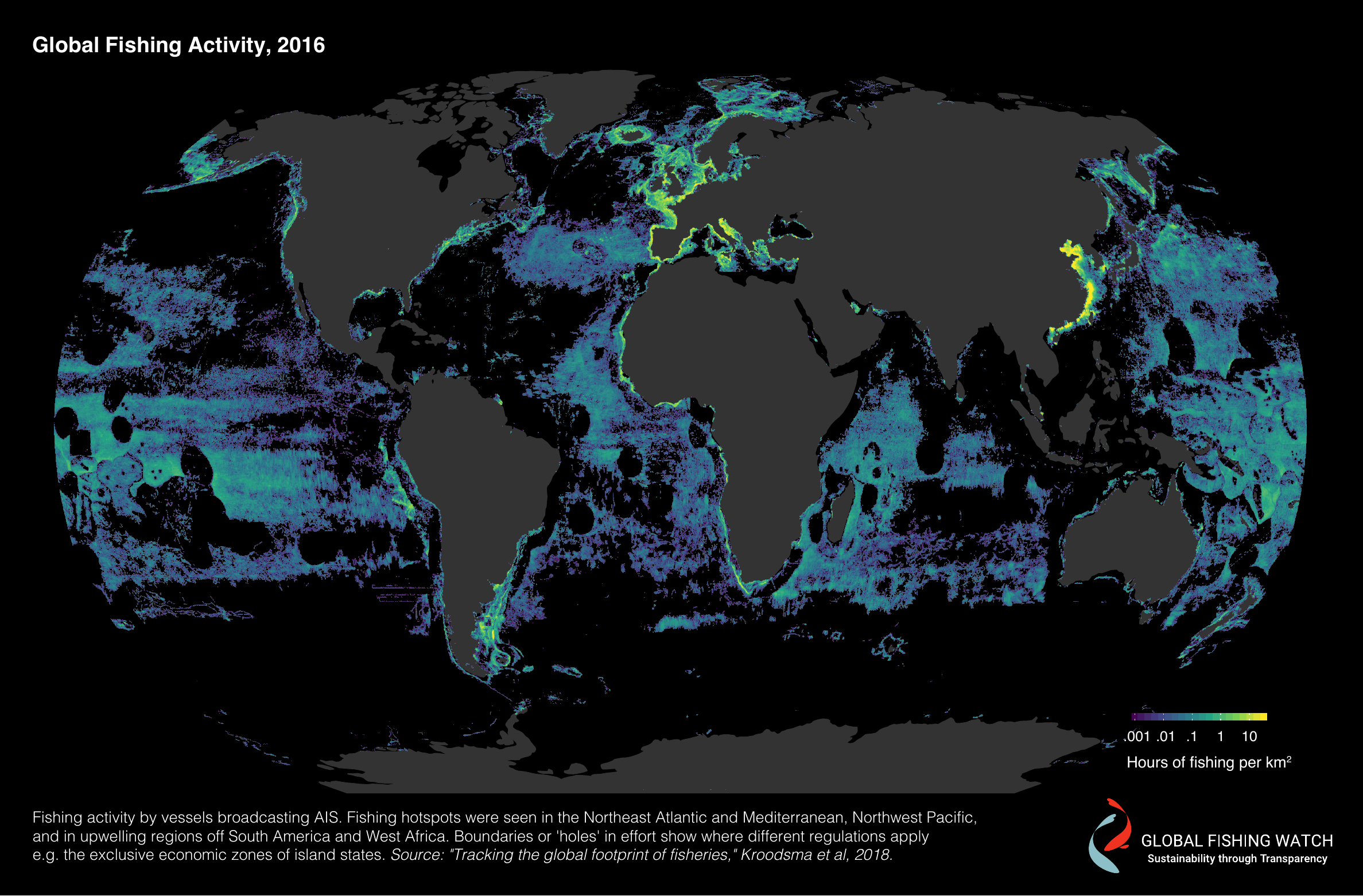

In February, we published the first-ever dataset of global fishing in Science. The study reveals that industrial fishing extends over more than half of the global ocean – making fishing’s footprint by area over four times that of agriculture.

Longline fishing for species such as tuna, shark and billfish, is the most widespread activity globally, detected in 45% of the ocean. And most remarkably, just five countries – China, Japan, Spain, South Korea and Chinese Taipei – account for 85% of all high seas fishing.

Further studies in 2018 have revealed that wealthy countries dominate industrial fishing at the expense of poorer nations; that without government subsidies and low labor costs, in some cases amounting to slavery, more than half of high seas fishing activity would be unprofitable; and that paradoxically, vessels may fish harder in anticipation of the creation of an MPA. And others model global patterns and hotspots of trans-shipment at sea; and the global footprint of pelagic longline fleets, showing that the ranges of tuna and other pelagic species may have contracted due to overfishing.

All this research draws on and would not have been possible without the novel data made publicly available through the Global Fishing Watch platform.

We plan to collaborate with more research partners in Europe, South America and Asia-Pacific to generate further science on fishing and its impacts.

Yet what’s most exciting to me is what comes next. We can now ask questions such as what parts of the ocean need more protection, or where different species are most at risk from bycatch, and we have the data to answer them.

Underpinning our work with sound science gives us the credibility we need to engage funders as well as national and international authorities, and again, 2018 has seen significant support for our work.

In the company of partners

This year, our founders have renewed their support – underpinning our ten-year vision – and new funders are helping ensure the technology behind Global Fishing Watch is making a difference on the water, allowing us to build for the long-term and engage governments.

At the G7 Summit in Halifax, we forged a relationship with Canada, leading to a Ministerial statement of support for our work as part of their commitment to invest $11.6 million to combat IUU fishing, and encourage better science and data sharing.

We also began working closely with Japan, and shortly before the G7 Summit, entered into an MOU with the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency (FRA), the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS) at the University of Wollongong to examine IUU fishing in the North Pacific.

The three-year collaboration will generate a much clearer picture of fishing activity in the North Pacific, including patterns of trans-shipment activity, and findings will inform decision-making by regional fisheries management organizations.

As early adopters, Canada and Japan have shown vision and quickly grasped the power and potential of our program. And with the G7 Charlevoix Blueprint for Healthy Oceans, Seas and Resilient Coastal Communities strongly reflecting our own vision and mission, the Summit saw the emergence of a powerful state-to-state dialogue on transparency. Global Fishing Watch offers a unique mechanism for the G7 to make data available and take practical action for ocean transparency.

We are also teaming up with the United States Coast Guard Research & Development Center (CGRDC) to conduct research on IUU fishing. The collaboration will be the first within our forthcoming Data and Analytical Cell and share findings with countries who might not otherwise have access to such information.

I am also keen that Global Fishing Watch becomes the first choice for NGOs looking for fishing activity analysis. This year we became a new member of the High Seas Alliance and we look forward to supporting high seas treaty negotiations – irrespective of the treaty’s approach to governance, transparency will be a major factor in its success.

We finished the year on a high note, finalising a significant program grant with Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Commonwealth Secretariat to collaborate on innovation, analysis and ocean sustainability.

Just add data

As we look to support governments, businesses and civil society in delivering SDG 14 and ending IUU fishing, our ambition is to catalyze transparency in global fishing by visualizing the fishing activity accounting for 75% of the world’s marine catch.

We are entering the age of transparency and it will transform ocean business as we know it.

We must exploit all possible means to better understand what is happening in our ocean. And we must strive to do this openly and publicly, ensuring the results are freely accessible.

Working together, we can combat illegal activity, reward responsible fishers, manage fisheries sustainably, protect marine life, and ensure ocean resources are available for generations to come.

Global Fishing Watch is committed to being part of the solution. We have the means to deliver near universal transparency, in a way that engenders trust and defeats corruption, and that minimizes the need for resource-intensive policing.

All we need to do now is add data – it’s a small step for governments but a giant leap for transparency and ocean stewardship.