Nuno Queiroz and a team of over 150 scientists recently published “Global spatial risk assessment of sharks under the footprint of fisheries” in the journal Nature. Tim White, Global Fishing Watch Fisheries Scientist, was a co-author of this study.

Nuno Queiroz and a team of over 150 scientists recently published “Global spatial risk assessment of sharks under the footprint of fisheries” in the journal Nature. Tim White, Global Fishing Watch Fisheries Scientist, was a co-author of this study.

Sharks of the open-ocean are some of the most threatened fish in the sea; around 75% of open-ocean shark species are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It’s incredibly difficult to improve the health of any species without knowing where it faces the greatest threats, yet clear information on where sharks are captured by fisheries doesn’t exist for most species.

In a new study, an international team of over 150 researchers used satellite tracking and Global Fishing Watch data to reveal where sharks and ships overlap at sea. Led by Nuno Queiroz and David Sims’ Lab at the Marine Biological Association Laboratory in Plymouth, UK, researchers from 26 countries took a big-data approach to shark conservation.

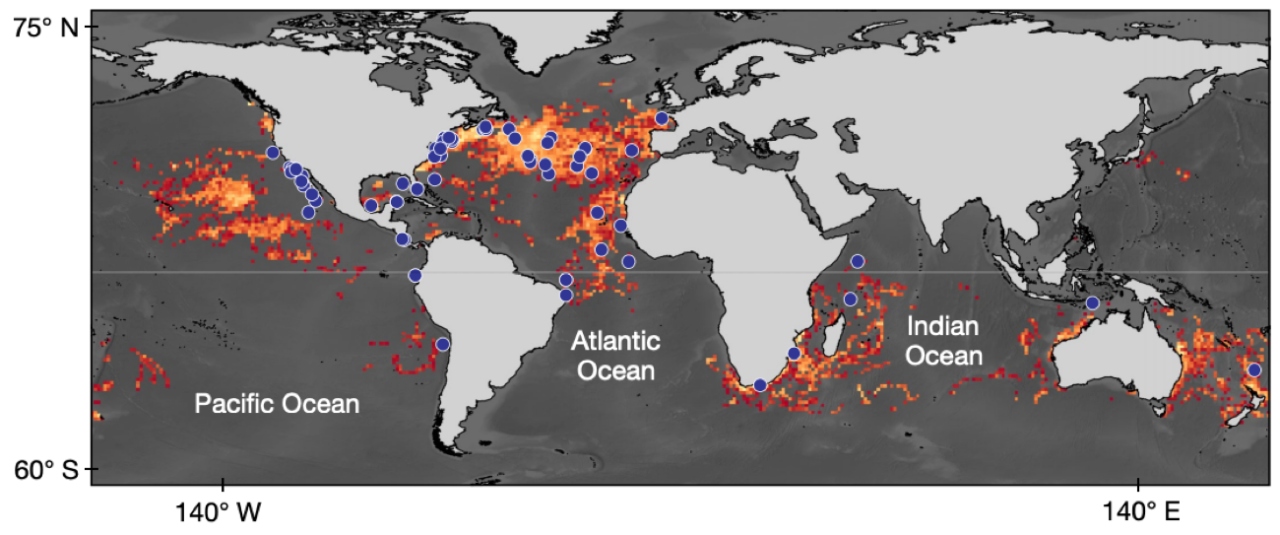

To identify the key shark habitat hotspots globally, the team compiled tracks from approximately 1,800 satellite tags on 23 different shark species including white sharks, whale sharks and hammerhead sharks.

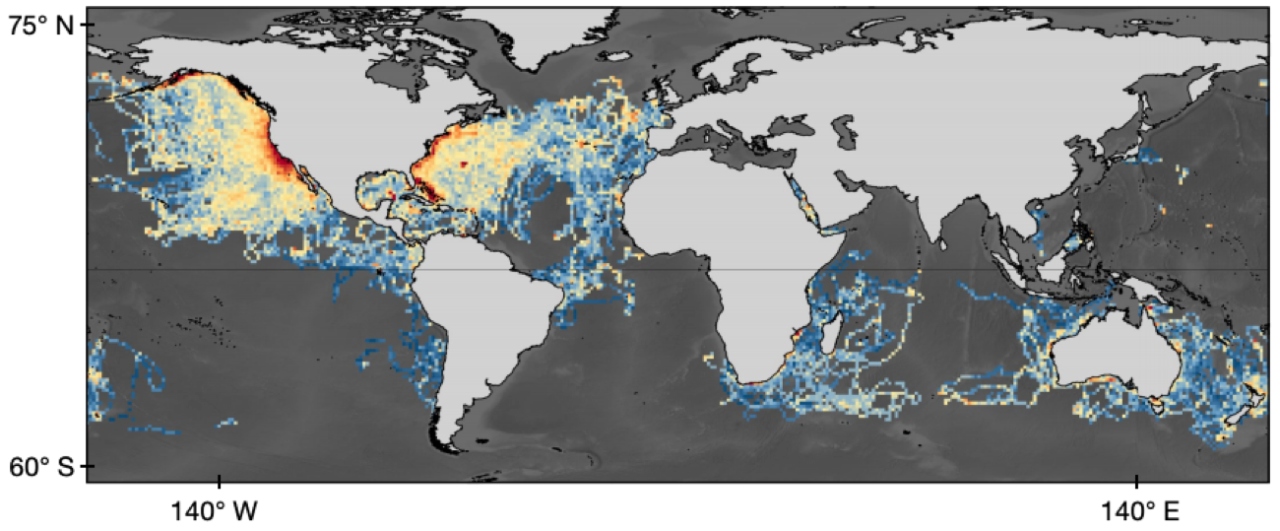

Next, the team downloaded Global Fishing Watch data on global longline fishing effort, which is publicly available on our website. Longliners catch the most open-ocean sharks globally and have relatively low rates of fisheries observers onboard to monitor bycatch, so vessel tracking provided valuable insights into where and when longliner hotspots may overlap with shark hotspots.

Combining shark movements and fishing effort produced a unique, global view of how sharks and fishing vessels overlap. On average, nearly one-quarter of the monthly space used by sharks overlapped with longliners, indicating that sharks have relatively few remaining refuges from fishing. The results are even more stark for some threatened species. Porbeagle sharks are listed as Vulnerable globally on the IUCN Red List, with the Northeast Atlantic subpopulation classified as Critically Endangered, yet over half of porbeagle shark space use overlapped with longliners in the North Atlantic.

Tracking sharks and ships is a crucial step towards understanding where sharks face the greatest threats and where we should focus our limited conservation resources. For instance, data-driven approaches like this can be used to figure out where large marine protected areas for sharks may be placed.

This study also exemplifies that an era of transparency and open data sharing is decisively underway in efforts to protect our oceans. Data on how sharks use the ocean – critical for their sustainable management and conservation – are being shared more openly than ever before. This mirrors the increasing transparency that we see in fisheries data, as more countries than ever before are publically releasing vessel tracking data to contribute to collective ocean health and reduce illegal fishing. A continued increase in data transparency will help us better understand how human activity at sea impacts species like sharks, and in turn, how we can best protect them.