NGO collaboration will help fishery managers ensure transfer of catch is both legal and verifiable

The transfer of fresh catch from fishing vessels to refrigerated cargo ships is an important but often opaque part of the industrial fishing sector. A new public global monitoring portal is a turning point in efforts to manage this activity.

Fulfilling the world’s demand for wild-caught seafood would not be possible without a large fleet of refrigerated cargo vessels, known as reefers or carriers, traversing the globe. These vessels often collect catch from fishing vessels far from shore, making it hard to monitor and control their activities. But things just got a whole lot easier.

Combining resources and technical expertise, Global Fishing Watch (GFW) and The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) have created the world’s first public searchable monitoring portal of carrier vessel activity, complete with vessel identity and authorization status. Accessible to anyone via GFW’s online platform, the portal provides important data to fishery managers and policymakers, which can help guide the reform of transshipment policies.

Transshipment – moving fishing catch from one vessel to another – is a vital but traditionally largely hidden part of the global commercial fishing industry. It can happen at sea or in port. Transshipment at sea enables fishing vessels to skip a trip to port so they can stay on the fishing grounds to fish longer without interruption. When it occurs beyond the horizon, outside of the jurisdiction of a port or coastal State, it is often out of sight and control of authorities. But even in port, limited inspection capacity or inadequate procedures mean that proper oversight cannot be guaranteed.

Transshipment touches a wide range of seafood products, including salmon, mackerel, crab, and especially tuna. A recent study estimated that in the western and central Pacific Ocean alone, more than US$142 million worth of tuna and tuna-like product is lost in illegal transshipments each year.

Moving catch from fishing vessels to carrier vessels is an economic choice aimed to reduce cost and preserve the freshness of the catch sent to market. But because of the lack of effective monitoring and control, bad actors can obscure or manipulate data relating to their fishing practices, the species or amounts caught, and catch locations. This undermines the ability to make supply chains more sustainable, and enables the laundering of billions of dollars of seafood from illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing. The lack of oversight undercuts conservation and management efforts and also opens the door for transnational crimes such as the trafficking of weapons, drugs, and people, and the perpetuation of poor working conditions for fishing vessel crew. Transshipment has to be better governed, and transparency in operations will help.

About the portal

Global Fishing Watch and Pew have been working to cast light on transshipment activities for several years. Previously, no public global database of transshipment activities even existed. Data on transshipments come in official reports from governments to the regional fisheries management organizations they are party to, generally in summary form, often a year or more after the fact. Our joint analyses have shown that official reports are often incomplete and thousands of possible transshipments on the high seas go unreported.

Developed collaboratively by GFW and Pew, the portal layers several datasets to build a picture of carrier vessel activities. It’s based primarily on the automatic identification system (AIS) signals transmitted by carrier vessels. AIS is a GPS-like device that large ships are legally obliged to use in order to broadcast their position and avoid collisions. Unlike fishing vessels, the vast majority of cargo vessels have AIS because it is mandated by the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea.

By combining data from public vessel registries and machine learning techniques, the portal will provide greater transparency and insights on transshipment activity.

Free to access, users – including regulators, policymakers and researchers – can pinpoint encounters between carrier vessels and fishing vessels, analyze the vessels’ tracks and identify the ports that carrier vessels use and frequent. The portal also includes a carrier vessel database with information on vessel authorizations and licenses, where publicly available.

The portal is a particularly powerful tool for port officials, who are on the frontline when it comes to identifying and sanctioning suspected illicit operations. With the use of the portal, a port official who has been notified that a given carrier vessel is headed their way will now be able to crosscheck and verify the vessel’s recent activity – both ‘official’ (declared) and ‘observed’ (tracked via the GFW system) – and its history of compliance elsewhere. This will enable the official to prioritize which vessels require further inspection, especially when they have limited inspection resources or capacity.

Below are some examples of how the portal can shed light on potential transshipment operations within the major tuna management regions.

Verifying carrier vessel activity

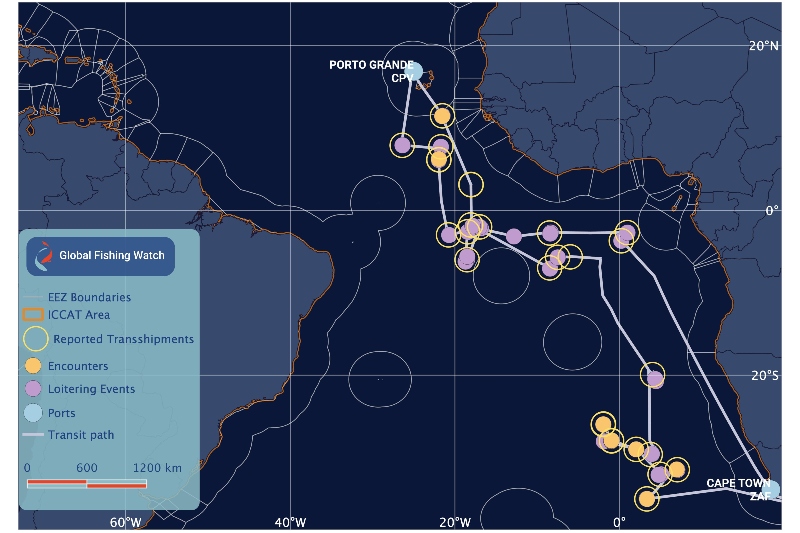

The carrier vessel portal can be utilized to identify vessels conducting transshipments in a transparent manner, authorized within a tuna RFMO, complying with the transshipment regulations, and consistently transmitting AIS.

The above image shows the track of an authorized Liberian carrier vessel voyage and the associated potential transshipment events. To explain this visualization, an encounter (yellow dot) is recorded when a carrier vessel and a fishing vessel are detected on AIS data as within 500 meters of each other for at least two hours and traveling at a median speed of less than 2 knots, while at least 10 kilometers from a coastal anchorage. This suggests a transshipment occurred. A loitering event (purple dot) also indicates a potential transshipment, but in this case only AIS data for the carrier vessel was provided. A loitering event is recorded when a carrier vessel travels at speeds of less than an average of 2 knots, while at least an average of 20 nautical miles from shore.

Overlaid with the AIS data are the reported transshipment locations (yellow circles) provided by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Regional Observer Programme. The high match rates on this map between reported transshipments and both encounters and loitering events indicate the effectiveness of using AIS data to detect and identify potential transshipments at sea. This can help management authorities monitor the activities of carrier vessels and ensure they comply with transshipment regulations. The data can also be used to crosscheck and verify activity reported by observers on carrier vessels.

Revealing suspicious behavior

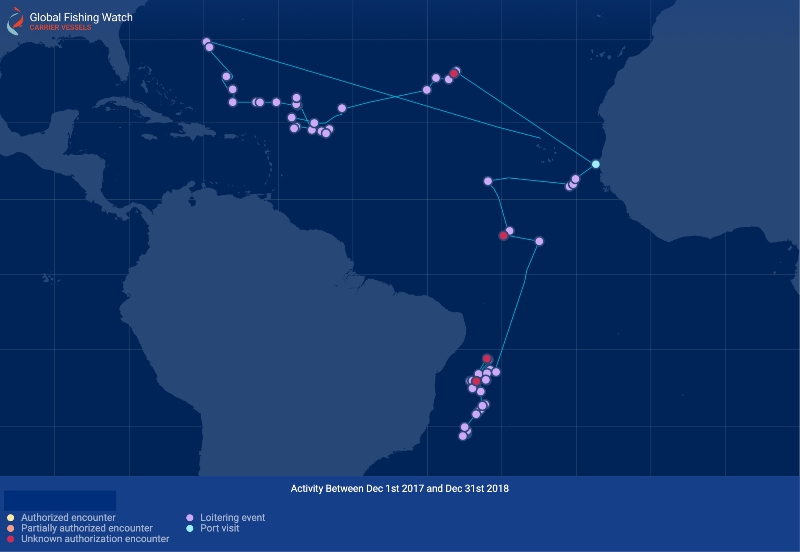

In the previous example, the close correlation between reported transshipments and transshipment events indicated by AIS data suggests the carrier vessel was operating in compliance with transshipment regulations and the observer system is working well. But the portal can also reveal potentially noncompliant activity.

In the above image, we see the track of a carrier vessel considered ‘inactive’ on the ICCAT registry list – a carrier vessel which did not appear to be registered at the time to transship ICCAT-managed species according to public ICCAT historical registry records. It had four encounters (red dot) and 58 loitering events (purple dot). We know from the ICCAT observer program that other reported transshipments between carrier vessels and fishing vessels took place in these waters around the same time. While it’s unclear what went on during these encounters and loitering events, these events were not reported in the ICCAT observer program. It’s possible that these AIS-detected encounters and loitering events involved transshipment of catch that went unreported to ICCAT.

Using AIS data in this way can highlight possible reporting anomalies, or even detect potential noncompliant behavior that may warrant further investigation or follow up.

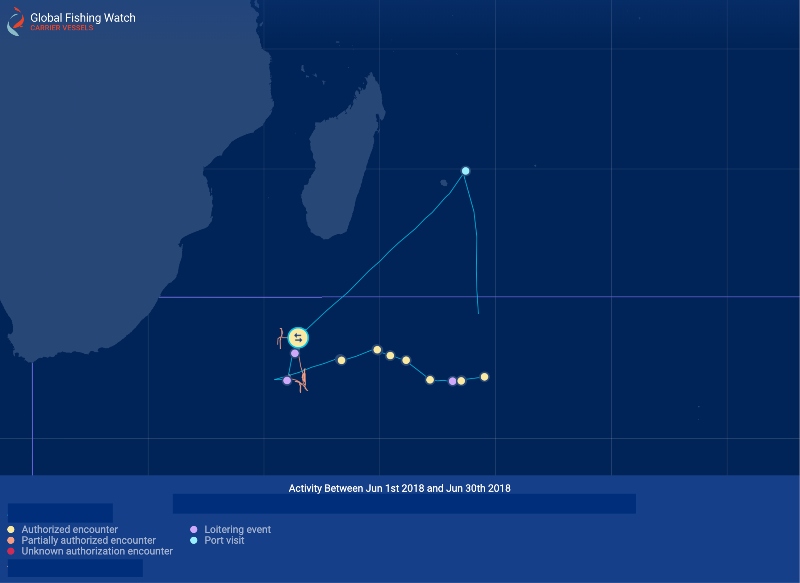

Tracking vessel activity between regional fisheries management organizations

The image above shows an encounter between a fishing vessel (orange track) and carrier vessel (blue track), in the Indian Ocean. This encounter (yellow dot) occurred after the fishing vessel fished in an overlapping regional fisheries management organization (RFMO) Convention Areas – the fishing and transshipment occurred in an overlap area between the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission. The movement of fishing vessels across and between different Convention Areas can make accurate monitoring and management of tuna species all the more difficult. By providing a clear history of a vessel’s fishing activity prior to a transshipment, the portal can help RFMOs exchange information effectively, and ensure the catch, and transshipment, is legal and correctly reported in line with each RFMO’s regulations to the relevant authorities.

A powerful tool to help guide reform

Reforming transshipment is integral to ensuring complete traceability and transparency in the seafood supply chain. Ensuring that all transshipment activities – regardless of where they occur – are legal and verifiable would significantly reduce opportunities for illegal practices, resulting in positive incentives for those in the fishing industry who do the right thing. Transparency of information helps generate self-correcting behavior, and this portal can be combined with other emerging solutions such as electronic monitoring (or electronic observer) programs.

Regulations across the many RFMOS differ greatly; these inconsistencies are exploited by unscrupulous operators. Establishing clear and consistent rules and monitoring requirements for transshipment, both globally and across RFMOs, is essential in ensuring a strong, legal, and verifiable seafood supply chain, as well as reducing the likelihood of other associated illicit activities. Analysis of carrier vessel activity arms policymakers with the evidence they need to reform transshipment. The often-hidden nature of transshipment has historically hindered policy reform globally, which is why it is a key focus for Global Fishing Watch and Pew.

While more data and transparency are needed, the carrier vessel portal is a giant leap forward in our ability to monitor and address the transnational challenge of transshipment.

Hannah Linder is a fisheries analyst for Global Fishing Watch.