This post originally appeared on our Data Blog

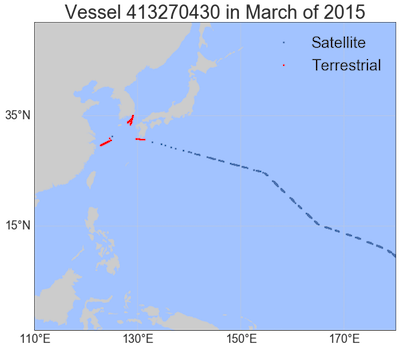

The sample vessel track below shows position broadcasts of the Jin Sheng No.2, a Chinese fishing vessel with mmsi number 413270430. Over three weeks in March of 2015, this vessel steamed from the central Pacific to the coast of Japan, Korea, and China.

While moving, a vessel broadcasts its position via AIS every 2 to 10 seconds, meaning that this vessel was likely broadcasting thousands of messages per day. These messages can be received either by satellites (the blue dots on the map), or by antennas on the shoreline (the red dots, labeled “terrestrial”).

On the map above, you will see that the blue dots are clustered with sizeable gaps between these clusters. These gaps occur because the satellites aren’t always overhead. You’ll also notice that the frequency of blue dots decreases as the vessel approaches the coast of Asia.

The red dots show where terrestrial antennas recorded the movement of this vessel. You can see that these antennas have a limited reception range and can only “see” so far from shore.

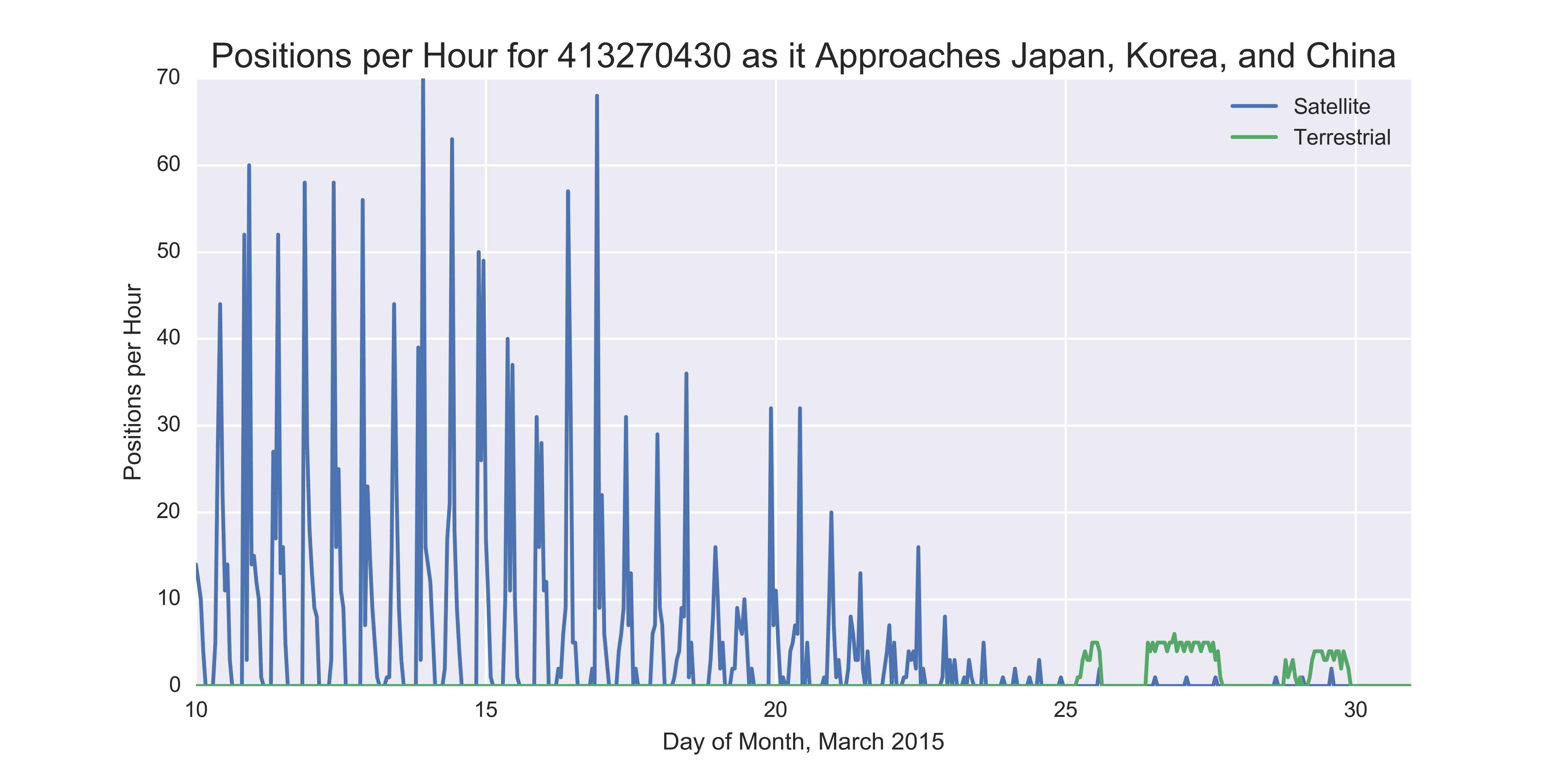

The following chart displays the number of positions per hour for this vessel over the same time period. When satellite reception is good, as in the central Pacific, we record more than 50 positions per hour. But each day there are several hours with no positions.

The number of positions received by satellite per hour decreases as the vessel approaches Asia. The reason is that a satellite can only receive so many AIS messages at once. Close to the coast of Asia, there are so many vessels that each vessel is “seen” less frequently by the overhead satellites.

The terrestrial antennas don’t have the same problem as the satellites, partially because a terrestrial receiver is affected by only the vessels close to it. Terrestrial antennas “see” a much smaller area of ocean and therefore receive fewer signals. A satellite can receive messages from a swath of ocean a few thousand miles wide, which means signals from the entire coast of Asia can interfere with each other.

The upshot is that in parts of the world where there are numerous vessels with AIS, such as in this example near the coast of Asia, satellites provide less reliable coverage of our vessels. Terrestrial antennas, on the other hand, provide a fairly reliable ability to track vessels, but they are limited in their range.

With the current number of satellites in orbit, there will always be gaps in AIS data received from vessels at sea, sometimes of several hours, but the number of satellites in orbit is increasing. This will both increase the number of positions we see in any given hour and reduce the gaps in satellite coverage.

You can see the code used to generate these maps in the original post on our data blog.

There is much more data, code, and description of our process on our data site for researchers and software engineers.