Darcy Bradley is a postdoctoral researcher at University of California – Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. Her recent publication in Conservation Letters, Leveraging satellite technology to create true shark sanctuaries, examined how advancements in tracking technology can help us better understand illegal fishing activity and therefore improve fisheries management.

What do you do when your ecological study takes an unexpected turn as a result of illegal fishing? It’s a question we were forced to ask ourselves when we noticed some suspicious looking tracking data from satellite tags deployed on reef sharks to follow their movements in the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI).

As a movement ecologist, I often use various animal tracking technologies – e.g. satellite tags, acoustic telemetry – and spatially explicit movement models to understand how the movement of marine predators affects the way in which we manage them. The launch of Global Fishing Watch has expanded my research program by giving me a new lens through which to understand the movement of a very different type of marine predator: fishers. Little did I know that my two worlds of marine predator movement were about to collide.

In December of 2015, I was contacted by a group who had deployed 15 satellite tags on grey reef sharks in and around Bikini Atoll in the RMI. They were very excited. Eight of their tags were showing unprecedented movement across open ocean. Were they onto something? Was this the manifest destiny of reef sharks in the tropical central Pacific?

“Nope,” I told them. With my recently acquired familiarity with vessel tracking data, I quickly and confidently became the bummer-scientist who quelled their excitement and smashed their big break. “Your tags are on boats.”

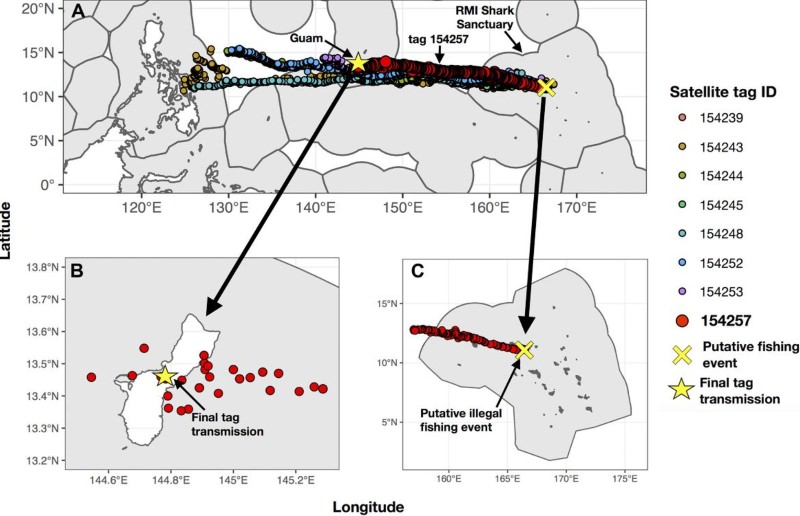

As the realization sunk in, we all understood that what we were observing was even more important than extraordinary animal movement. The RMI is a “shark sanctuary” – the commercial fishing of sharks is banned within all ~2 million km2 of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) – and yet more than half of the sharks tagged as part of an ecological study had almost certainly been illegally fished. If that rate of illegal shark fishing were to occur over the entire sanctuary expanse, it could drive its population of reef sharks to less than 10% of a healthy population size in less than five years.

We contacted local authorities to alert them of the putative crimes, but the vessels carrying our shark tags were already underway, likely on to their next fishing destination. And on they went… one vessel ended up in the Port of Guam, and the tag sent a final transmission from a location near the Guam airport. Another set of vessels wound up at port or in the waters surrounding the Philippines, over 4500 km away from the suspected fishing location in the RMI.

Unfortunately, we were never able to identify the responsible vessels because none of the eight boats suspected of illegally fishing sharks from within the sanctuary were carrying an automatic identification system (AIS) tracking device. This struck us as a missed opportunity worth addressing.

Monitoring the activity of all vessels within vast and remote shark sanctuaries is a non-trivial task, but we suggest that satellite technologies can be used to fill in surveillance blind spots and improve the ability of shark sanctuaries to truly protect sharks. To that end, we offer a plan that utilizes existing international agreements such as regional fisheries management organizations and the Port State Measures Agreement to actualize the use of satellite technologies for better monitoring and enforcement. We suggest that international management bodies can act as implementation mechanisms, and treaties can bolster shark sanctuary legislation by ensuring that illegal shark fishing within a sanctuary has international repercussions. Shark sanctuary nations have an exciting opportunity to harness the expertise of a growing community of data scientists with an expertise in vessel monitoring – largely due to the efforts of Global Fishing Watch – to ensure that the much-needed protections promised to sharks within sanctuary borders are realized.

Read Darcy’s publication, Leveraging satellite technology to create true shark sanctuaries, to learn more about this research.