Eric Galbraith is an ICREA research professor based at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Jerome Guiet is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. Read their new study.

Most of the activity that Global Fishing Watch monitors is carried out by industrial fisheries, working for profit. These businesses are run and staffed by people who live on land, like the rest of us. But at the same time, the targets of the fishing fleets are wild animals – residents of the largest untamed ecosystem on the planet.

As scientists trying to understand the interactions between fishing fleets and fish populations at the global scale, we know that the natural cycles that shape life in the oceans drive many changes throughout the year. Great blooms of plankton come and go, and many fish swim long distances on migrations, sometimes crossing ocean basins. But we really had no idea how much global fishing activity responds to the natural seasonal cycles of the ocean, rather than just being driven by business concerns and government regulations determined on land – until Global Fishing Watch came along. Armed with three full years of the Global Fishing Watch data (2015-2017), we were set to take a look.

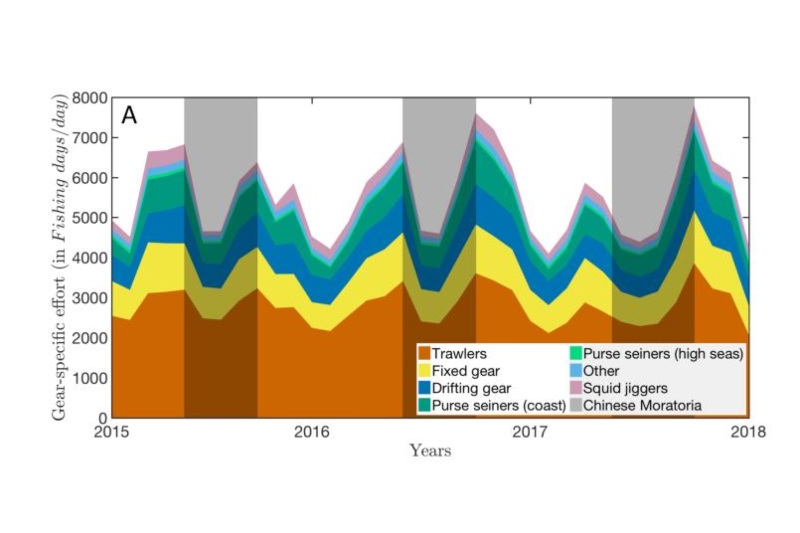

When we first went through the data, the first thing that jumped out was the massive importance of the annual Chinese fishing moratorium. This management policy puts a huge dent in overall global fishing activity every summer, when the Chinese government prohibits fishing in their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) for 2-3 months. This makes for a lull in fishing, followed by a huge surge of fishing activity once the moratorium ends. Because there are so many Chinese vessels, it makes for a strong seasonal cycle in the global data – a pattern driven only by government regulation, rather than environmental factors.

When we filtered out the Chinese EEZ data, the seasonality almost disappeared from the global fishing effort. The little seasonality that remained can be explained mostly by wintertime holidays in industrialized countries. Aside from those, the total number of boats seen by Global Fishing Watch that are fishing during any given month varies by only a few percent over the year, like the number of people working in factories or offices.

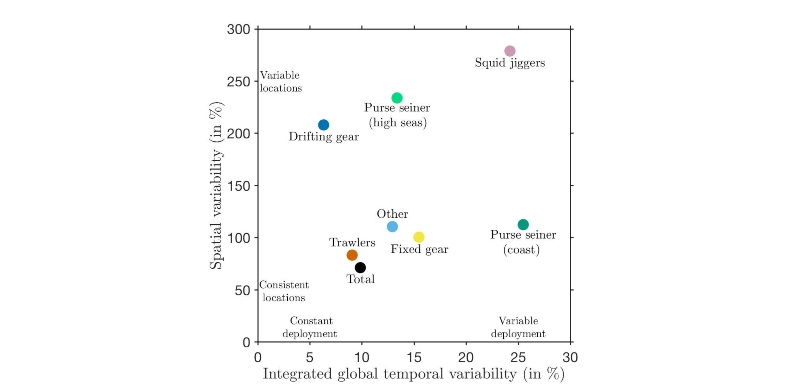

However, when we took a closer look using Global Fishing Watch’s gear-specific data, we found several subtle but important differences that are hidden at the global scale. Sure enough, most of the gears that target fish living on the seafloor, close to shore – like trawlers, traps, and bottom-moored lines – fit the overall picture of little change over the year, with the fleets generally working the same patches of seafloor, day in and day out, throughout the year. But the boats targeting fish that swim freely, away from the bottom – purse seines, drifting gears, and squid jiggers – showed a lot more variability. The global picture shows that the places these gears are deployed shifts seasonally, as you might expect for boats hunting wild animals that respond to seasonal fluctuations in their environment. And although drifting gears and high seas purse seine fleets operate at a pretty constant level throughout the year, coastal purse seiners and squid jiggers show strong seasonal peaks in total activity as well.

Getting to the bottom of why these seasonal shifts occur is tough, since there is such a huge range of different species being targeted, by boats from ports all over the world. But the most likely driver of seasonality lies in the behavioral ecology of fish. Many fish change their behavior throughout the year, migrating to places where they are easier to catch, forming schools that can be scooped up by purse seines, or going after hooks more often. This can explain why we see fishing patterns on the high seas shifting seasonally over thousands of miles, and why the seasonality is more pronounced for fisheries targeting fish that don’t live on the bottom.

Global Fishing Watch has revolutionized the way we see fishing across the global ocean. Our close look at the data shows that although most fishing, especially near the coast, pays little attention to the natural rhythms of the sea, on the high seas that cover 43% planet’s surface, the seasons still play a big role in deciding when and where people go to fish.