When we click ‘buy’ online or check out at a retail store, we don’t often think about massive ships moving our products across the ocean. Yet we are all connected to the marine shipping industry by the goods we use every day. As the connectors of the global economy, cargo ships move up to 90 percent of the world’s trade, and have a significant impact on the ocean and climate. This impact is felt most literally by endangered whales that can suffer fatal injuries when whales and ships collide in an increasingly busy ocean.

In order to better understand—and help reduce—the impacts of shipping on endangered whales, scientists from the Benioff Ocean Initiative at the University of California Santa Barbara are using Global Fishing Watch data to monitor shipping traffic patterns in important whale habitats in near real-time.

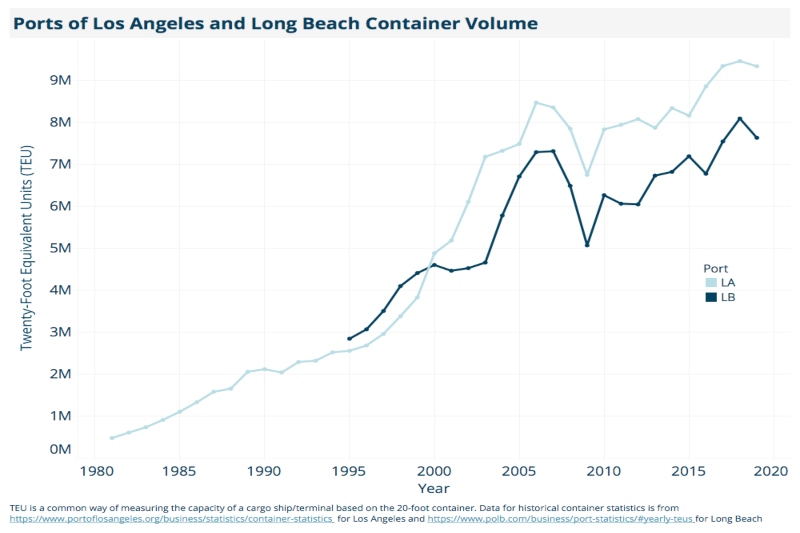

Great whales were hunted nearly to extinction in the 19th and 20th centuries, and while the threat posed by commercial whaling has decreased significantly, the threat from ship traffic has grown exponentially. An international moratorium on commercial whaling was passed in the 1980s, but since that time, marine shipping, as measured by increases in container port traffic, has risen by approximately 1600 percent. Busy ocean highways used by large ships often intersect with important whale habitats, leading to an increase in fatal whale-ship collisions around the globe.

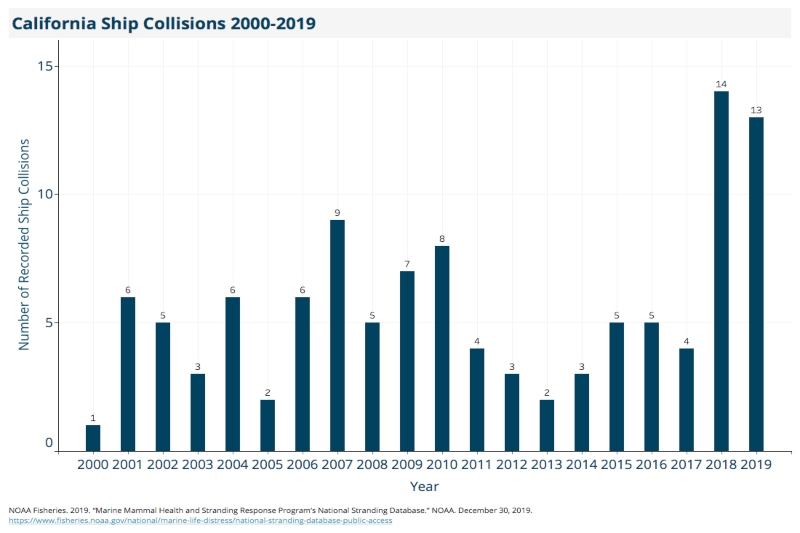

Off the coast of California, 2018 and 2019 were the worst years on record for whale-ship collisions. Scientists estimate that over 80 endangered whales are hit and killed by ships off the U.S. West Coast each year, which is significant for slow-growing whale populations that have not fully recovered from the days of intensive whaling. High-risk areas often occur near ports where shipping traffic is dense, and where whales may be feeding, migrating, or breeding in productive nearshore waters.

The Santa Barbara Channel off the coast of Southern California is a prime example of a location where ships and whales meet. An incredibly rich biodiversity hotspot, the Channel serves as important feeding grounds for endangered blue, humpback, and fin whales. At the same time, within the Channel are internationally designated shipping lanes where thousands of large cargo ships travel to and from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, one of the busiest port complexes in the world.

In this region, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Coast Guard implement voluntary vessel speed reduction zones, requesting that large ships slow to 10 knots or less to protect endangered whales during times of peak whale activity. Research has shown that slower ships can save whales, in some cases reducing the risk of fatal whale-ship collisions by up to 80-90 percent.

Benioff Ocean Initiative researchers are analyzing Global Fishing Watch data in the vessel speed reduction zone to bring transparency to the shipping industry and highlight which ships and companies are—or aren’t—slowing down to protect endangered whales in the Santa Barbara Channel. The team has produced shipping report cards for the major international companies, and is releasing them this week with the launch of Whale Safe, a new tool providing near real-time data insights on whale and ship activity to help reduce the risk of fatal collisions.

In the Santa Barbara Channel slow speed zone, the researchers’ analysis of Global Fishing Watch automatic identification system (AIS) data has shown that 56 percent of the shipping industry exceeded the 10 knot speed limit in 2019, with 14 percent of ships speeding at 15 knots or faster. So far in 2020, outcomes are looking slightly better, with 44 percent of ships exceeding the 10 knot speed limit. Still, incremental improvements in cooperation with these speed limits may not be enough to protect these endangered species, especially since 2020 has been a record year for blue whale activity in the Santa Barbara Channel with aggregations of over 30 whales observed feeding near the shipping lanes.

In addition to protecting endangered whales, slower ships provide additional benefits including cleaner air and quieter oceans. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) recently adopted a target to reduce the total annual greenhouse gas emissions by the international shipping industry at least 50 percent by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. While new technology is being developed to improve the efficiency of ships, speed reduction may be the only short-term option capable of achieving the emissions reductions necessary to meet IMO targets.

A 2019 study published in Frontiers in Marine Science reported that a 10 percent speed reduction across the global shipping fleet could reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions by 14 percent, improving the likelihood of meeting IMO targets by 23 percent. This study also found that the 10 percent speed reduction could reduce ocean noise pollution by 40 percent and could reduce the risk of fatal whale-ship collisions by 50 percent.

However, to achieve these multiple benefits for both ocean and climate health, ships must slow down, and monitoring and enforcement of speed restrictions is necessary. Information on shipping industry cooperation with slow speed zones was not publicly available until now, and researchers hope that the clients of these shipping companies, major importers and exporters, will use this information as part of their sustainability planning and prioritize working with whale-safe shipping companies.

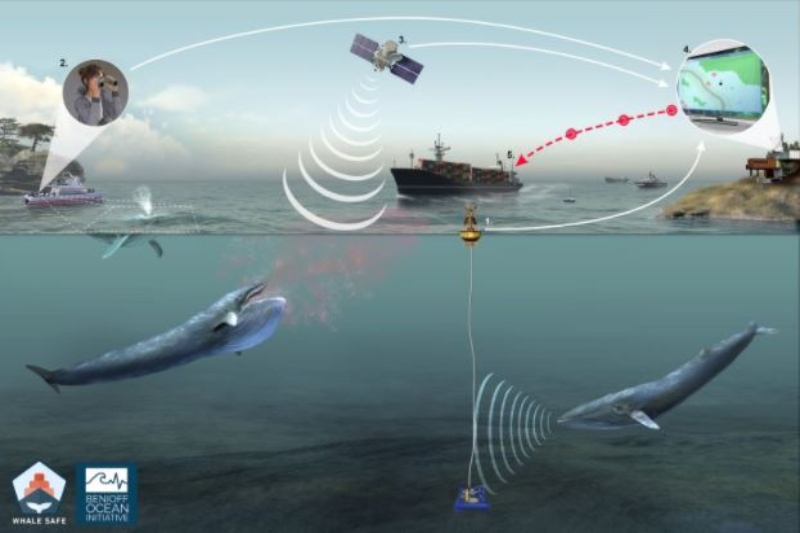

In addition to monitoring ship traffic, Whale Safe collects and shares near real-time data on whale activity in the Santa Barbara Channel. It’s the first system to use ocean sensors powered by artificial intelligence and big data models to track both whales and ships, with the goal of reducing the risk of fatal collisions. It incorporates three whale detection technologies: an acoustic monitoring system that automatically detects whale calls, whale sightings recorded by community scientists using the Whale Alert mobile app, and new models providing near real-time forecasts of blue whale feeding grounds. Together these datastreams can provide the shipping industry, government officials, and the public with a daily assessment of whale activity in the Santa Barbara Channel to help empower more data-driven decision making for whale protection. Whale Safe is a collaborative effort of scientists from the Benioff Ocean Initiative, University of California, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Texas A&M University at Galveston, the University of Washington, EcoQuants, and National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

Ongoing monitoring of whale-ship collisions and shipping speeds will be used to evaluate the tool. If successful, Whale Safe could be replicated in other ship strike hotspots around the world to help whales and ships coexist.