Are whaling vessels that operate without using aids to avoid vessel collision putting the safety of biodiversity and people at risk?

This week the International Whaling Commission (IWC) has convened in Slovenia. The gathering marks the 30th anniversary of the commission’s moratorium on commercial whaling. This landmark action has been hailed as an incredible environmental achievement. Nations, including our own, that had historic and cultural connections to whaling collectively decided to stop whaling in the interest of ocean health. With this cooperative global action, we managed to bring some our ocean’s most ecologically important and charismatic great whale species back from the brink of extinction.

Photo: Whit Welles/ Creative Commons

Despite this international moratorium, several countries, including Japan, have continued to carry out commercial whaling justifying it as scientific research.

The International Court of Justice ruled in March 2014 that Japan’s whaling program in the Antarctic had violated multiple provisions of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. In 2015, at the last IWC meeting, a resolution was approved requesting that no more lethal research be carried out without the IWC Scientific Committee first assessing and approving the work. Despite these declarations from the international community, Japan resumed whaling in the Southern Ocean during the 2015/2016 season, killing 333 Antarctic minke whales.

One less explored facet of Japan’s whaling activities in international waters concerns their use of the Automatic Identification System (AIS). AIS is the same big data source that powers Global Fishing Watch. It was originally conceived and implemented as a safety system to help prevent vessel collisions at sea by sharing the location of ship traffic.

The International Maritime Organization, via the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), developed safety protocols for use of AIS. SOLAS requires that all vessels of 500 gross tonnage and above operate AIS at all times. Japan codified SOLAS safety regulations in its own domestic laws.

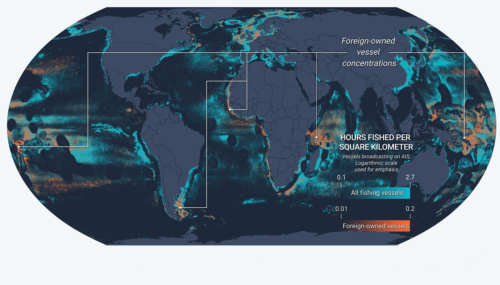

How well is Japan’s whaling fleet following these safety measures? The data suggest not well at all. During the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 Antarctic summers, Japanese whaling vessels largely turned off their AIS safety devices while hunting whales in the Southern Ocean. These whaling vessels all exceed 700 gross tonnage, well above the size threshold for which SOLAS regulation would require continuous use of AIS.

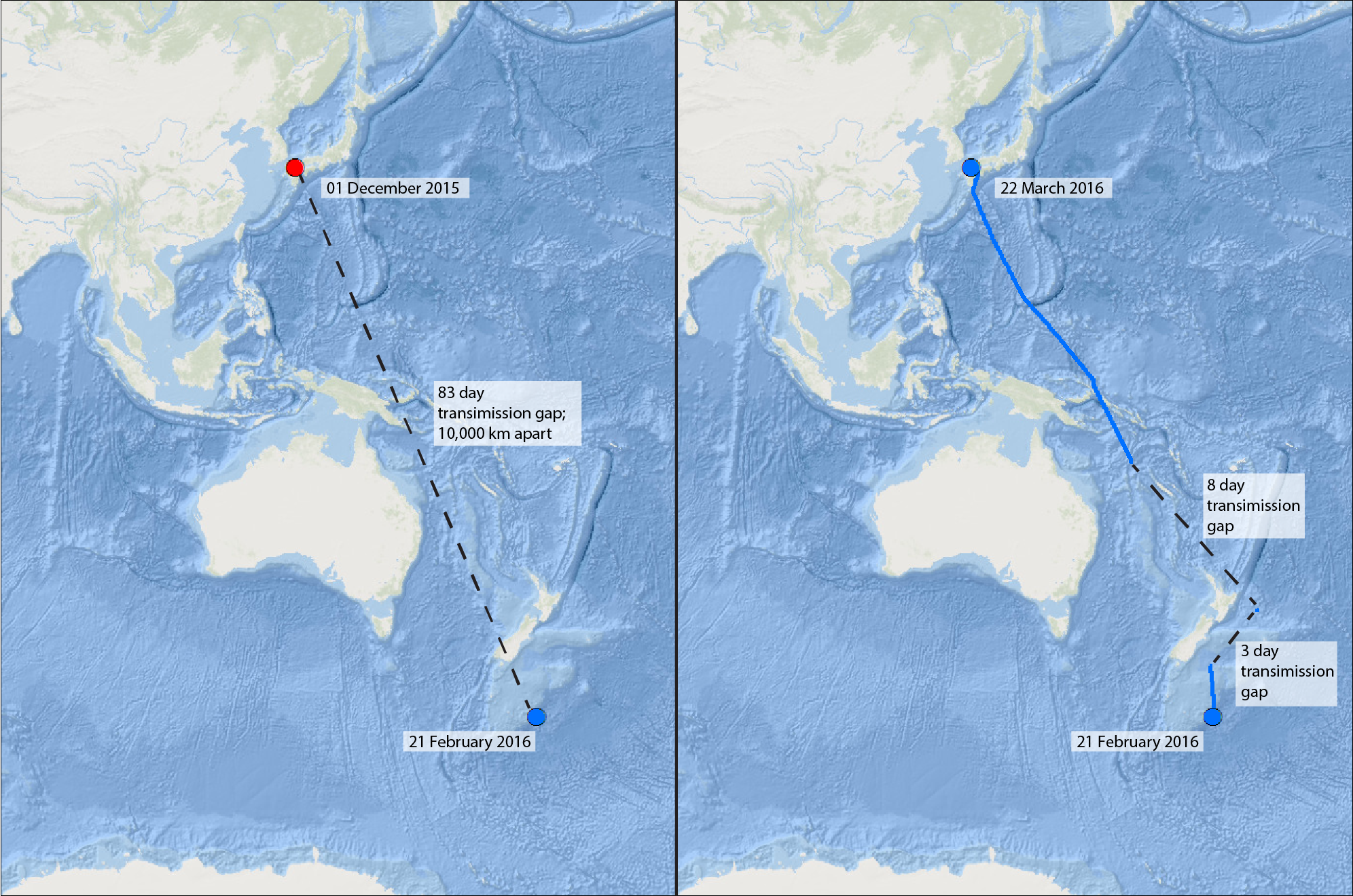

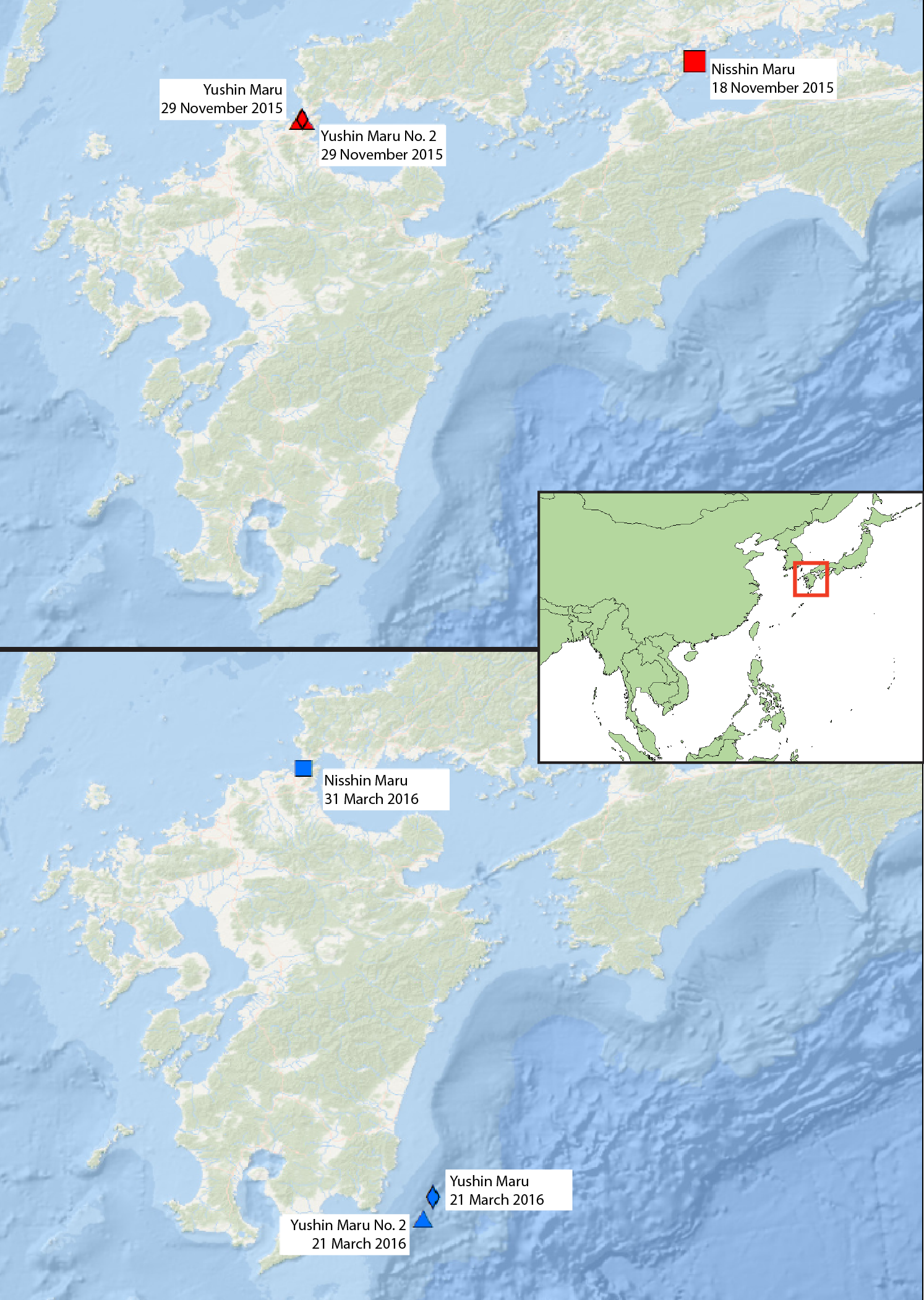

Take for example the case of the Shonan Maru No. 2, a Japanese vessel that has been documented to be engaged in whaling activities in the Southern Ocean. On December 1, 2015 an AIS position placed the Shonan Maru No. 2 at a port in the Kanmon Straits near Kitakyushu, Japan. The next AIS position is transmitted 83 days later, on February 21, 2016, in the Southern Ocean. The vessel continued to travel back to the Japan, arriving to the Shimonoseki port on 22 March 2016.

Three other vessels in the whaling fleet have AIS tracks in mid-November 2015 at ports in Western Japan, that then disappear until late March 2016 when they turn up back in port near Kitakyushu, Japan or near Sendai, Japan. This includes the vessel, Nisshin Maru, which was reported to be participating in the Antarctic whaling season of 2015-2016.

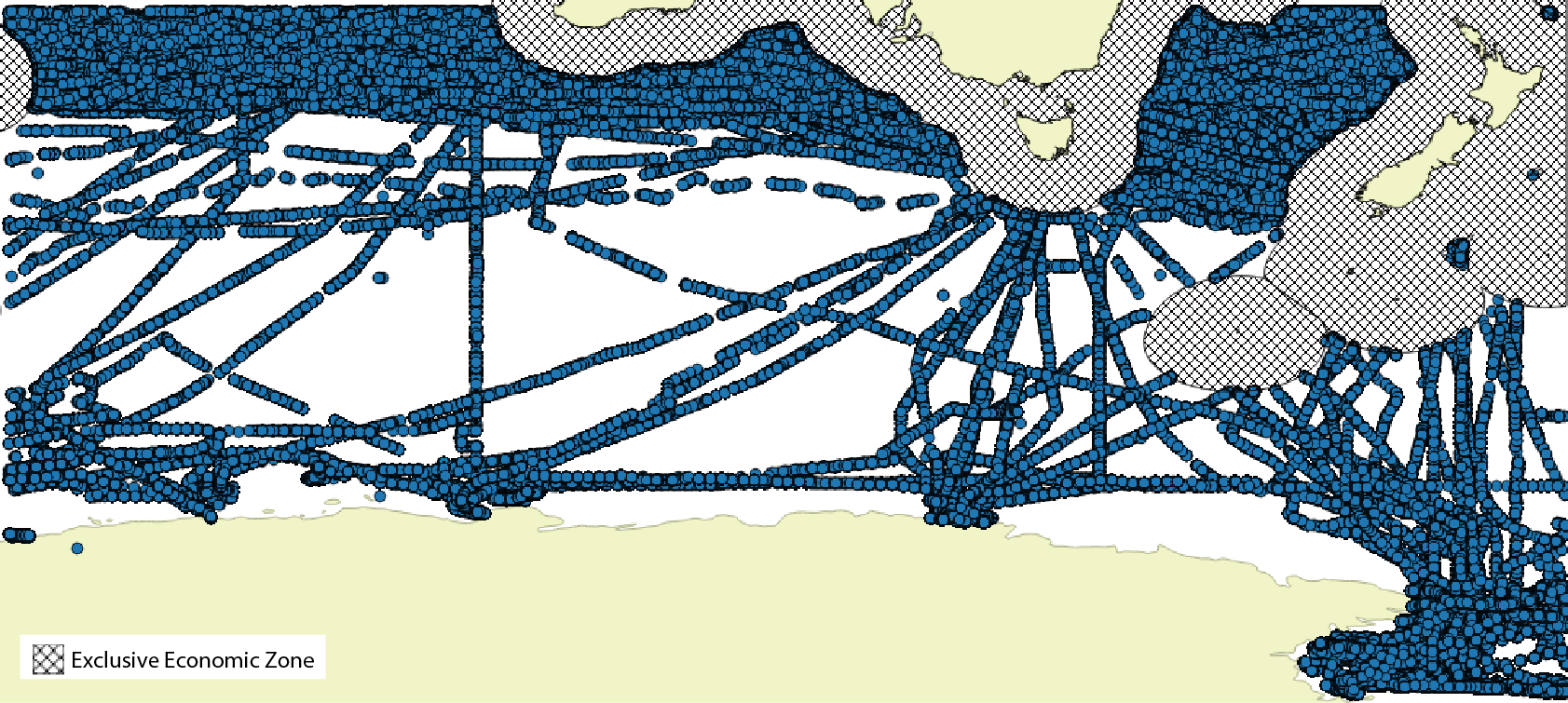

In some areas of the world, extended blackouts may be the result of insufficient satellite coverage or crowded airwaves from high vessel density. However, satellite coverage in the Southern Ocean is exceptionally good, and data analysis by Global Fishing Watch suggests that these AIS signal blackouts represent periods of time in which vessel AIS devices were intentionally turned off. From January – March 2016, AIS tracks for myriad vessels are visible in the Southern Ocean, which is characteristic for other years. Vessels navigating the southern ocean include fishing boats, research vessels, and tourist cruise ships.

The remoteness, harsh weather, and frigid water of this polar ocean region would make it a particularly tragic place for a maritime accident to occur, and should demand extra diligence with respect to safety measures, not less.

By using their AIS safety system to reduce the risk of vessel collision Japan’s whaling operations would also confer the added advantage of transparency. Sharing cruise information with all nations whose responsibility it is to co-manage biodiversity in these fragile and rapidly changing international waters would reduce the appearance of secrecy that raises suspicions of wrongdoing.

Japan’s whaling operations are the only research expeditions that we are aware of that operate with their AIS blacked out.

Photo: Customs and Border Protection Service, Commonwealth of Australia /Creative Commons

If Japan’s whaling vessels are indeed not complying with national and international regulations for safe ocean travel – this is a matter that we would want maritime legal experts to look into further.

The International Whaling Commission discussions underway this week provide a valuable forum in which to consider the risks associated with the decision by many of Japan’s whaling vessels to turn off their AIS safety systems.

If Japanese whaling cruises were required to responsibly use their AIS, that would reduce the risks these vessels are now posing to both ocean ecosystems and human safety.