Last year, Dr. Doug McCauley told the New York Times that humanity may be on the verge of creating a mass extinction in the seas unless we can rapidly change our course. McCauley and his colleagues had just published a paper in Science magazine on the health of the oceans that drew a lot of attention for making such a bold statement. The paper also concluded that, although humans are driving unprecedented rates of marine habitat loss, pollution and overharvest, the oceans remain healthy enough to recover under the right care.

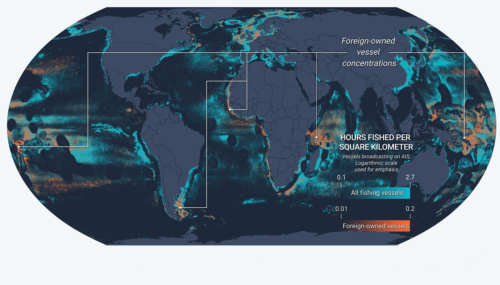

More recently, McCauley and a team of research partners, including Global Fishing Watch’s Bjorn Bergman, Brian Sullivan, Aaron Roan, and Paul Woods, authored another article in Science magazine that offers a new tool for guiding that care. In the article “Ending Hide and Seek at Sea,” the authors assert that managing the oceans at large enough scale to be meaningful will only matter if we can see what’s happening out there and then act on it. Their work demonstrated the power of AIS data and big data processing to pull back the curtain on the most remote parts of our ocean, areas that have been largely invisible to governments, management organizations and researchers like McCauley who seek to chart a path that both serves our needs and preserves diversity in the wild long into the future.

Shortly after the article was published, we talked with McCauley about the article, his expectations for big-data in fisheries research, and his source of hope for a sustainable future for the oceans. Watch the short video excerpt of our conversation and read more from McCauley below.

What do you think was one of your biggest take-home messages from the recent article in Science?

That paper was a wonderful experiment for a team of scientists to try to get our heads around what the real potential was in this tool and this dataset. We described it in a couple of different ways in the paper as being like turning on a light in a dark room. Suddenly you can see what’s happening around the room. You can see all the interesting things we can now talk about and questions we can begin to answer. It was exciting to demonstrate the role of Global Fishing Watch data in helping move forward the conversation about the future of high seas policy and management. We’ve just basically touched the tip of the iceberg, and I think we realize that there are hundreds of really interesting research and management questions that can be answered.

One of the most exciting things that came out of that paper was the many e-mails from colleagues who are really interested in the value of the data for all kinds of research applications –from working on whales, to evaluating the usefulness of protected areas in the middle of the high seas. Those kinds of emails really deepened my awareness of all the powerful things you can do with this tool.

What are some of the scientific questions you would like to explore with the data?

We’re considering a case study in Australia to see if we can answer questions about how people are using the oceans around marine protected areas on the Great Barrier Reef.

In two decades of research on since marine protected areas came on line, we’ve recognized a couple of important services; first they’re protecting biodiversity inside the area, but secondarily, they are by design sourcing some of this biodiversity to fishermen on the outside with an overflow of fish from these super productive areas into surrounding waters. There’s a sense that fishermen line up on the boundaries of marine protected areas to reap these benefits.

What we’re doing with Global Fishing Watch data in Australia, is asking whether we can actually see fishermen lining up to preferentially spend time and effort fishing right on the edge of these marine protected areas. That’s important, because again, it helps us understand how people are using ocean space, and how we can make sure to zone it in a way that works well for them and the industry. It also gives us good evidence that marine protected areas are working well, because if there’s nothing else unusual about that boundary, there’s only one good explanation for why people are concentrated there. It’s because that marine protected area is working, and it sources more food to these communities via the fishermen.

You’ve said we’re on the verge of an industrial revolution in the oceans. Will you explain what you mean by that?

Everyone’s familiar with the industrial revolution that happened on land, where we had this rapid and explosive growth of new kinds of industry. That was a positive thing for humanity in terms of being able to get more food, and products and energy more efficiently, but it happened in a really dirty fashion. We didn’t have awareness that this progress needed to be interlinked with progress and maintenance of health in our environment. We didn’t know that our fate in a way is linked with the fate of the environment. We ended up polluting our water, destroying forests. There’s lots of biological regret on many levels about damage that persists in ways that could have given us all of the good of the industrial revolution with a lot less of the bad.

Now if you look at growth trajectories for new industries today, most of what I see suggests that, we’re sitting right at the beginning of what could be an industrial revolution in the seas. The industries I’m thinking about are things like marine mining, we’ve never minded in the oceans, and now we’re actively prospecting and exploring those lands right now. We’re considering all sorts of new power generation in the oceans. This is kind of a mixed bag because we need low carbon, or carbon-free energy, and the ocean has a whole lot of that to give us, but that means a whole lot more hardware, be it tidal turbines, wave energy or offshore wind.

Just a couple years ago we passed a transition point where, for the first time in human history, we farmed more fish for human consumption that we caught wild in the oceans. That for me is as important as this transition point on land when we stopped going out to the forest to hunt and gather our dinner, and instead started growing it, and growing it at industrial scale. That’s happening now in the oceans. There’s a lot of this industry that is just starting to take off.

How can science and governments help guide that growth toward a better outcome than what we have seen with the previous industrial revolution?

Using these same types of data technology that Global Fishing Watch depends on, we can map out where all of that new development is happening. If you can actually figure out where these new actors and industries need ocean space, then you can manage it properly. Kind of the way you would zone out a city space, to say well you have mining over here, you have fisheries here, you have a whale migration route there. Suddenly you’re in a much better position to sit down with all the stakeholders and say, “OK, let’s synthesize all this data it in a way that produces a map that moves forward industry innovation and also keeps food coming in and biodiversity healthy. I think a key component to that is going to be using tools like Global Fishing Watch because it brings to the table data about where and how fishermen use the ocean.

Thinking about my own personal history and my relationship to the oceans, I think it’s unfair that people think of this data as a way to watch bad actors in the fishing industry. The reality, of course, is that there are very few bad actors. Most of the people on the water are doing a really hard job to catch healthy food for communities, and so the data that’s stamped in global fishing watch tells us how all the good guys are actually using the oceans. It tells us the story of the good guys so we can think about building out this future that’s compatible for fishermen, for mining, for whales–and all the other stakeholders in our ocean future. We need to have high quality source of information about what fishermen need and that’s Global Fishing watch.

Maybe it’s a good time to talk a little about your personal history with the ocean and fisheries.

I began as a fisherman. I grew up in Los Angeles and worked as a fishermen out of Los Angeles Harbor through high school and during summers in college. I worked as a deckhand on sport fishing boats. We would take 25 to 75 passengers out and fish for anything that was within a day’s reach from Los Angeles.

I loved doing that, and I fell in love with the ocean, with what a wonderful beautiful and complex place it was. At that point in my life my passion and curiosity were focused on trying to figure out how fish use the ocean so I could catch more of them for my customers.

Eventually I realized that my talents and predilections were maybe better suited for engaging that same complexity and that beauty through the vantage point of science, so then of course I trained to be a marine biologist, so now I’m looking at it from a slightly different perspective.

From the perspective of a scientist and a fisherman, what gives you hope that we can solve the problems oceans face today?

They’re awfully big problems and they’re moving really fast. But here’s the thing, if you compare this to the industrial revolution on land, there’s very little we can do about the mistakes we made then. That game has played out and we can’t bring back the land-based species that went extinct for example.

In the oceans, we’re just beginning this process of rapid change, but from new perspectives. We now get that ocean health matters for our own wellbeing. We understand that the future of the ocean affects how much nutrition developing countries get, how much nutrition our own communities here in the US get. It effects the economy of fishing communities and of course that translates to billions of dollars annually.

We’re ahead of the curve because we have a realization of the problem, and people realize we have to do something about it. So the questions becomes one of whether we have the tools to be able to make the right decisions. In some ways, technology is causing the problems, but it can also fix the problem.

Technology is allowing us to do a bunch of new things to fish in the deepest parts of the oceans and to start marine mining, but it’s also allowing us to see where all of this is happening. I think that the power of these brand new big data streams for seeing how people are using the oceans is really going to be our salvation for securing a 200 to 500 year healthy future for the seas in a way that we didn’t do for industrialization on land.