A second wave of the coronavirus could exacerbate future fisheries damages

Global fishing activity has been in decline since the COVID-19 pandemic began. From the start of 2020 fishing activity has decreased by approximately 6.6 percent, and it has dropped nearly 7.9 percent since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic on March 11.

But the Japanese fleet is a different story.

Japanese fishing has actually increased, or stayed the same, during this period of global fisheries decline. But despite this increase in activity, it appears that less catch is being landed at Japanese ports.

In our upcoming paper with Iwate University’s Resource Economics and Policy Group, Global Fishing Watch seeks to investigate why less catch is being landed despite hours of fishing remaining unchanged.

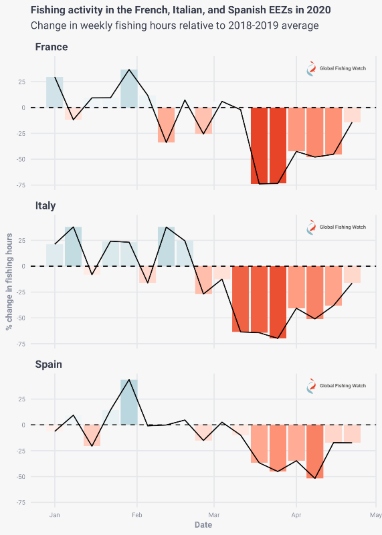

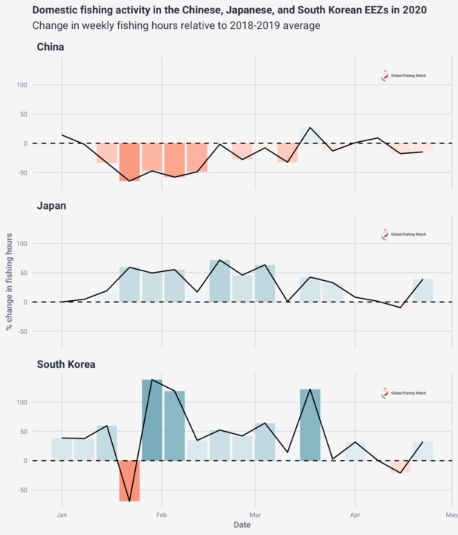

Figure 1: Change in hours of fishing for different States in comparison to the same period of time during previous years

Because fishing by Japanese vessels is greater or similar to previous years, it might be assumed that the Japanese seafood industry is still thriving. This is, however, not the case. According to weekly trading reports provided by Toyosu Market from April 10, the daily trade volume for fresh fish decreased by about 30 percent from the year before (469 tons), while tuna was halved to 19.7 tons. Thus the wholesale price of tuna went down about 70 percent lower from the year earlier, approximately 2910 yen ($27 USD) per kilogram on average.

Milestones in COVID-19 Impact

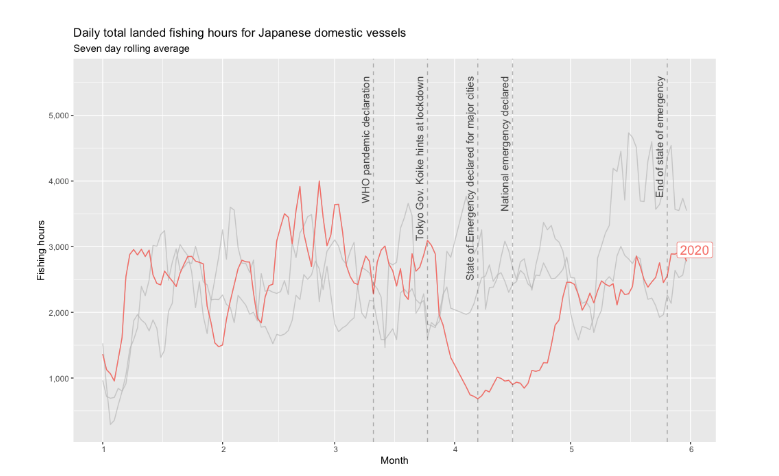

To understand why Japan is experiencing a decrease in price but an increase in fishing activity, which was driven by economic incentives, we looked into the hours of fishing in Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) by the Japanese domestic fleet, regardless of port stops, and the total number of fishing hours from when a vessel left port to return to port.

Our findings reveal that COVID-19’s largest negative impact took place from March 25 to mid-April. It seems that landed hours of fishing started to rapidly recover in late April and early May. Yet, even with the recovery the overall landed fishing hours were still 12 percent lower than May of 2019. And relative to May 2019 the Japanese domestic fleet had a nearly 50 percent increase in hours of fishing within its EEZ, but had 12 percent fewer landed hours of fishing in 2020 relative to 2019. This could signify that the Japanese domestic fleet is staying at sea for longer periods of time than usual.

While other nations such as Spain, Italy, China, and France had major disturbances in fishing activity during their lockdown periods, Japan’s state of national emergency from April 7 to May 25 seemed to have less of an impact. This decline in landed fishing hours in Japan may be linked to other COVID-19 milestones. Looking deeper into a timeline of the major COVID-19 related events that occurred within Japan, we see that the initial decline in fishing hours appears to be closely tied to Governor Koike’s announcement that the Japanese Federal Government was planning a lockdown. The landed fishing hours for the Japanese fleet stayed low until the end of April.

While fishing activity across the board decreased after Governor Koike’s announcement, drifting longline vessels, especially those between 15 to 20 tons, were the most negatively impacted. This is likely due to the fact that many drifting longliners mainly catch high-end tuna products which may have lost demand with the economic uncertainty, closure of restaurants, and other COVID-related factors. With the suppressed demand and lower prices caused by the closures of high-end consumptions, it is possible that the vessels increased fishing hours at sea in order to make up for their decreased landing values and increased quantity. These excess fishing efforts could negatively impact targeted fishery resources.

Alternatively, in conjunction with a new Japanese fisheries reform policy that institutes quotas based on 2020 catch logs, a fisher’s increased landings would expand their future quota share under diminishing total landings. This would lead to diminished return from targeted fishery resources.

Thus, despite the rebound in May, the unpredictable climate created by the COVID-19 pandemic makes determining the future impact on the Japanese supply chain and Japanese domestic fleets’ performance difficult. As of August 2020, Japan seems to be in the midst of the second wave of COVID-19, which is likely to once again cause a similar disturbance across the Japanese domestic fleet. The increase in cases also lines up with the peak months of Japanese fishing activity in July through September. If a similar decline happens, the repercussions on the Japanese fishing industry may be more serious than the previous situation in April, especially for the domestic drifting longline industry.

So, if the fishing activity has increased but the demand has decreased domestically in Japan, where is the fish going, how is the market reacting, what is being caught and which prefectures are being affected the worst?

Over the next few months, we will conduct further analyses of the possible impacts on the Japanese supply chain to assess the possible damage that may develop as a result of the increase in COVID-19 cases and another possible lockdown.

Gunther Errhalt is a regional fisheries analyst for Global Fishing Watch.

Read in Japanese: COVID-19 は日本漁業にダメージを与えていたが漁船は活動的だった