Large scale, commercial fishing activity has often historically taken place out of sight – fishing grounds far from shore make them difficult and costly to monitor, jurisdiction considerations impede governance and a patchwork of regulations have not kept pace with advances in fishing technologies. As our global seafood consumption has increased, so has the impact on our oceans and life below water. But, in a world heading towards 10 billion people, seafood is critical to global food security.

Sustainable Development Goal 12; Responsible Consumption and Production, aims to ensure sustainable production and consumption of all natural resources. Considering global seafood production peaked at about 171 million tons in 2016 and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing costs up to $23.5 billion every year, the sustainable management of fisheries is needed more than ever. Pacific Island countries, home to some of the world’s most productive and valuable commercial fisheries, have been working together to tackle IUU fishing and sustainably manage what for many is their most valuable natural resource.

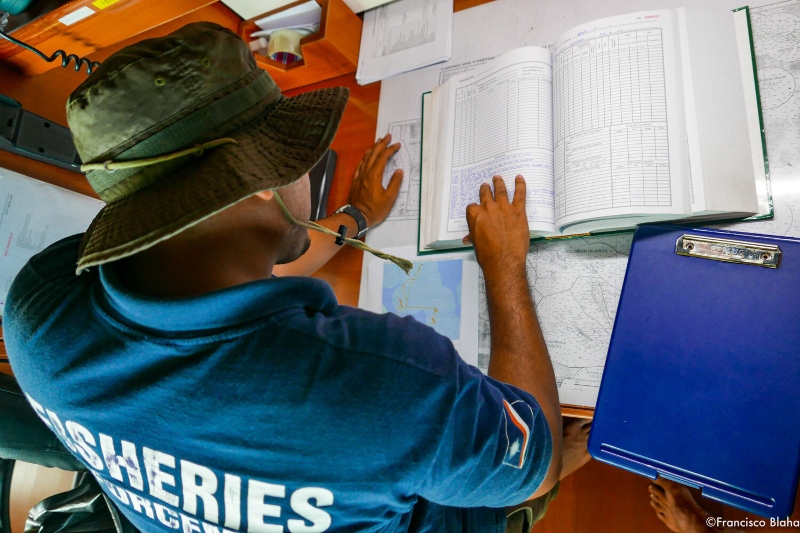

Considering the importance of the Pacific region to ensuring global sustainable consumption and production of seafood, we discussed how technology and transparency can be embraced by the fishing industry to realize SDGs 12 and 14 with Francisco Blaha, International Fisheries Consultant. With over 29 years experience in supporting and collaborating with Pacific governments and institutions on operational implementation and capacity building programs, Francisco has seen first hand the impacts of ensuring sustainable consumption and production of seafood in the region:

Q: Fishing is part of life for so many people in the Pacific region, is there a focus on sustainable consumption and production of seafood?

After having spent half of my life in the Pacific, fishing for tuna is more than just a job to me. I’m one among the estimated 22,000 people in the Pacific whose livelihoods depend directly and completely on tuna fishing.

Fishing for Islanders is much more than food, it is part of their culture and identity. As an example, in some Pacific languages, there are many different words for the different ways that fish school and break on the surface, the same way Inuit communities have various names for the different types of snow. Survival was associated with fishing.

“Fishing for Islanders is much more than food, it is part of their culture and identity.”

With the advent of offshore commercial fishing and Pacific Island Countries (PICs) sovereign right to fish as coastal States, fishing became a key driver to their economies through fishing rights, as well as employment and diplomacy. For many Pacific Islands, revenue from granting access to fishing is the principal income earner, and for the Distant Water Fishing Nations (DWFNs) catching the fish, having access to Pacific tuna is a matter of economic survival. The Pacific tuna industry produces some 256 million cans of tuna annually, amounting to U$D 7.5-8 billion, yet around only 800-900 million of this revenue comes back to PICs.

Tuna is the lifeline of the Pacific but the balance of benefits is entirely skewed, in a way that has not moved far from the times of colonialism. And this is an issue of overarching importance since competing interests are impacting tuna sustainability. There is a fundamental (and perhaps unbridgeable) difference; as clearly expressed to me, by my Nauruan friend and colleague Monte Depaune: “for non-PICs and DWFNs the issue of sustainability is one of long-term financial benefit. However, for coastal States PICs it is also an identity and food security issue, one that DWFNs have less trouble with, as they can leave… but PICs cannot”.

Hence the focus on sustainability is evident, you’ll see that the Pacific coastal States via their regional organizations, The Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) and the Pacific Community (SPC), have a powerful mandate on how fisheries are managed by The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). The tuna stocks under their management are an example of good management. Strong leadership from the Pacific Island countries has shown to the world that industrial fisheries can be managed and not overfished. Things are not perfect and there is always potential for improvement in various areas, but in comparison with other tuna fisheries in other oceans, the Pacific Islands have shown a unique leadership based on a mix of self-driven regional consensus, advanced use of new technologies and ancestral cultural values.

“…the Pacific Islands have shown a unique leadership based on a mix of self-driven regional consensus, advanced use of new technologies and ancestral cultural values.”

Personally, the Pacific and its tuna gave me a new and good life when I came here in the early 90s, escaping far from my origins and struggles. The region gave me more opportunities than my own country of birth without expecting from me anything other than honesty and respect. But most importantly it gave me many good friends and an extended family in places that barely figure on maps, yet there is more “humanity” here than in countries whose “empires” cover the earth.

Q: How does IUU fishing impact communities here?

An excellent report in 2016 commissioned by FFA on the quantification of IUU fishing in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean found that the main issue for the region is under- and misreporting, rather than illegal in terms of unlicensed/unauthorized fishing, non-compliance with other license conditions (e.g. fish aggregating device (FAD) fishing during the purse seine closure period) and post-harvest risks (e.g. illegal transhipping).

For many years now the Pacific Island nations have shown substantial leadership in terms of coastal States rights and responsibilities. Regional unity has produced, just to name a few:

- A unique set of Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) tools like the regional Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) run by the Regional Monitoring Center in Honiara with feeds into every country;

- The four FFA coordinated regional surveillance operations using all the regionally available assets (plane and patrol vessels) plus the help of the New Zealand, Australia, France and US forces;

- Solid registers like the FFA Regional Register of Fishing Vessels (RR) list of vessels in good standing, (for those that are in compliance with the Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions for Access by Fishing Vessels), for all vessels intending to fish in the regional waters;

- The regional observer program;

- The Niue Treaty, which is an agreement on cooperation between FFA members about monitoring, control and surveillance of fishing MCS – it includes provisions on exchange of information plus procedures for cooperation in monitoring, prosecuting and penalizing illegal fishing vessels; and

- Sub-regional Fisheries Information Managements Systems of PNA (PNA FIMS) and the registers of vessels by the WCPFC Record of Fishing Vessels (RFV).

Combined, all of these initiatives contribute to the low impact of the “illegal” component of IUU in the region.

“For many years now the Pacific Island nations have shown substantial leadership in terms of coastal States rights and responsibilities.”

For us in the Pacific, the estimates of underreporting are dominated by the licensed fleet – assuming catch transhipped illegally is taken by licensed vessels, IUU fishing by the licensed fleet accounts for over 95% of the total volume and value of IUU activity estimated here. This proportion rises to 97% if unlicensed fishing by vessels that are otherwise authorized to fish in the Pacific Islands region (i.e. they are on the FFA RR or WCPFC RFV) are considered part of the ‘licensed’ fleet. This implies that, based on the expected species composition and markets, the ex-vessel value of the best estimate figure, the region is losing around $153m worth of fish every year (details of how this figure has been calculated can be found here).

This is a notable percentage of the revenue that comes into the Pacific Island countries, many of them being Least Developed Countries that depend substantially on fisheries related incomes for their annual budgets.

Q: What solutions are Pacific Islands pursuing to tackle IUU fishing and advance sustainable management?

The better you know the nature of your issues, the better you can manage them. The key issues of reporting data in fishing is not only the veracity of the information, but also the time frame in between the fishing event and the data being received at fisheries administrations for the equally important and interlinked purposes of compliance, science and policy. So, the Pacific, through the vision of its leaders, has been ahead of the pack with innovations in management and technology.

The Pacific has been very supportive in terms of reference points, effort controls, fish aggregating device management and so on, plus unique management measures such as the PNA Vessels Day Schemes for purse seine and longline vessels, whilst countries like the Cook Islands have successfully introduced a quota management system for its longline fishery. The recent incorporation of standardized port State measures through the WCPFC Conservation and Management Measure and FFA port State measures regional framework is further example of this vision, and one I’ve been working substantially on.

We are also starting to talk about novel solutions such as incentives for compliance schemes, where we could provide cheaper access to the fishery (or simpler) for operators that have a good compliance history, whilst making it more expensive (and more complicated) for those who don’t. The idea is that those that comply consistently with the rules receive benefit and recognition whilst at the same time those who don’t get penalized for their poor compliance history.

“The idea is that those that comply consistently with the rules receive benefit and recognition whilst at the same time those who don’t get penalized for their poor compliance history.”

Another area where the Pacific has shown unique leadership so far, and I believe it is part of sustainability, is the momentous move that FFA Member States made by using their Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions for Access by Fishing Vessels (HMTCs) on fishers labor rights, when they included a minimum set of requirements based on ILO’s Working in Fishing Convention (C188) as part of the requirements for the vessels to be allowed to fish in coastal State waters. This is momentous because from 1/1/2020, if a vessel does not uphold those labor rights and conditions as part of their licensing, then their right to fish can be removed and the vessels would not be in good standing. This is the first time in the world that there is a direct link between labor standards and the right to fish being substantiated by a coalition of coastal States!

The main issue that I learned in the Pacific is that to deal with issues in fisheries you need a toolbox and not just a hammer. When you only have a hammer, then you start to see every problem like a nail… and that is never the case.

Q: Why is information sharing and fisheries transparency so important in the Pacific?

We are in the biggest ocean in the world where over 60% of the world’s catch of tuna originates. The Pacific has taught me many things I treasure, a fundamental value I have learned is that you are just not an individual, you are always part of a bigger group with principles and history; you discuss things around the common good and common threads, social capital is more important than just individual drive.

Pacific leaders (albeit the substantial cultural differences they have) have always understood that unity and collaboration are the best approaches against the divide and conquer strategies they sometimes face. Whilst there is little they can do in terms of managing the High Seas, they are themselves Large Oceanic Nations instead of Small Island States, and in their waters they have the last word.

In the fisheries world the power shift is moving to the ones with the fish from the ones with the boats, even if the latter are richer and more influential. Without the strong cooperation and cultural linkages among Pacific Islands coastal States that I have been honored to witness and learn from, I doubt there would be a healthy tuna fishery such as the one they now have.

“Without the strong cooperation and cultural linkages among Pacific Islands coastal States that I have been honored to witness and learn from, I doubt there would be a healthy tuna fishery such as the one they now have.”

Q: Should the global fishing industry actively step forward and pursue greater transparency in fishing activities? What benefits can this bring to the sector?

I was a fisherman, I come from industry, and I have yet to find a fisherman who wants to get himself out of a job by collapsing a fishery. Yet what really irks me the most, is the general perception that all commercial fishermen are horrible people bent on destroying nature. They are harvesting food, no different from a farmer. Whilst there are some very unpleasant rogue people out there that push the limits of legality, that applies to any form of food production, not just fishing.

For me, sustainability is a process, not a line drawn somewhere. Everything has advantages and disadvantages, and we have to navigate ethical choices since there is no one perfect way to achieve a complex goal. With science, we can determine what kind of fisheries management will lead to long-term sustainability of food production, thus, in turn, feed fisheries policy that can set up the harvesting regimes needed. Then, MCS ensures stakeholders obey the rules set and measure the outcomes, that feed back into the science… and so the process restarts its cycle forwards. It is like a table with 3 legs, if one does not work, the table falls.

A recent paper I read shows that in regions where fisheries are intensively managed, stock abundance is generally improving or remaining near fisheries management target levels, and the common narrative that fish stocks are declining worldwide will depend on the spatial and temporal window of the assessment.

Finally, we need to understand how to use management approaches that leverage healthy stocks into sustainable economic and social benefits for the fishing industry and fishing communities. Transparency (from both sides – industry and administrations) is the basic thread for all this to happen, as it is the one that guarantees that no one is taking advantage of the rules of the game. Fisheries administrations need industry and industry need fisheries administrations… the better and more open systems we have, the more we all stand to benefit.

“Transparency is the basic thread for all this to happen, as it is the one that guarantees that no one is taking advantage of the rules of the game.”

Yet, I’m also very aware that the drive for sustainability and transparency is one that comes from a position of privilege. I live now in a developed and rich country, but I work all over the world. Of the people I work with, around 15% live below 1 USD a day and around 45% live below 2 USD a day (this is the segment where my mother’s family comes from and where I grew up). At present, 71% of the world’s population earn less than 10 USD a day, in other words… almost 3 of every 4 people on our planet earn less per day than the cost of a bottle of wine at a western supermarket. The definitions of efficiency, governance and sustainability are decided by western rich countries that comprise the top 29% of the population, the ones that can afford to plan for a future… We are very good at forgetting that too.

In my personal opinion, the incredible level of income inequality in our societies is the biggest sustainability tragedy of our world. If we are failing to look after our own in such a catastrophic way, what hope is there for everything else? I believe that sustainability in fisheries (as in any other primary production area) will only be able to be managed with real long-term prospects after we have dealt with our own collective failings in addressing inequality as a society.

What gives you reason to be optimistic about the future of sustainable consumption and production of seafood?

It gives me hope and optimism to see the way there is more diversity in fisheries now than ever before (even if we have a long way to go). More and more I work with amazing female colleagues in the Pacific, again leading the way, having more female heads of national and regional fisheries organizations than most other parts of the world. Equally I’m encouraged by younger upcoming people that are shredding the inherited colonialism structures, whilst at the same time having gained their qualifications in the system that oppressed them, and that is no small feat. I’m delighted to see people coming into the fisheries MCS and management realms from a much wider set of backgrounds than ever before.

I’ve been in fishing all my life, started at 17 and I’m 55 now, and I am still learning every day from my (and others’) mistakes, on strategies that I see working and those that don’t. If my gender, age and background represent the only way to do things, then how come we are facing the problems we have? How hypocritical would it be of me to not listen to new voices, new perspectives, new ways to do things. The fact we have this diversity is what keeps me optimistic.

Effective management solutions and monitoring, control and surveillance activities embrace technology and are tailored to the needs of the fishery and the region. Examples can be seen in the Pacific region and are needed across the sector. Fishing industry organizations can support implementation of such measures by committing to information sharing and collaboration to ensure responsible consumption and production of seafood, vital to ensuring life below water is utilized sustainably to address growing food security issues.

Courtney Farthing manages the global transparency program at Global Fishing Watch.