Nearly 200 Iranian vessels detected in Somali and Yemeni waters represent one of the world’s largest illegal fishing operations.

Global Fishing Watch (GFW) and Trygg Mat Tracking (TMT) have been working with partners in the Northwest Indian Ocean region, including the Somali government, to identify large-scale illegal fishing that is occurring inside the waters of both Somalia and Yemen. The activity taking place is likely one of the largest illegal fishing operations occurring in the world.

The detailed findings of our analysis can be found in our joint Fisheries Intelligence Report, which has been submitted to the Somali government, and communicated via their press announcement. The report has also been shared with the relevant states through the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) and Fish-i Africa.

Reports of widespread illegal fishing in Somalia’s waters have been ongoing for some time and have been historically linked to the piracy problems in Somalia. However, the scale of the problem was unknown until fishing vessels in the region recently started using automatic identification system (AIS) – a collision avoidance system that continuously transmits a vessel’s location at sea. The analysis of this data has identified a fleet of predominantly Iranian vessels operating extensively in the Somali and Yemeni exclusive economic zones (EEZs), and on the adjacent high seas. A smaller subset of Indian, Pakistani and Sri Lankan flagged vessels have also been identified in these areas.

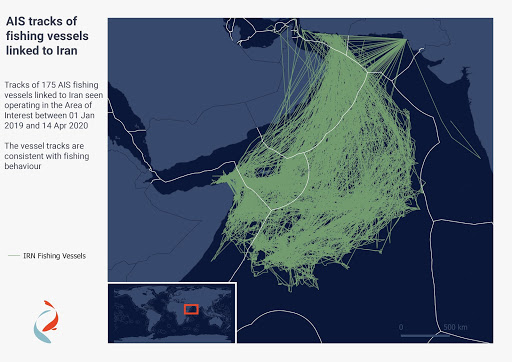

An increase in visibility of these vessels in 2019 is linked to growing availability of AIS equipment for use on vessels, and drifting buoys that are attached to fishing gear to mark and track them. The GFW and TMT analysis of these AIS signals identified 175 individual Iranian vessels on AIS that are fishing predominantly in the Northwest Indian Ocean, beyond the Iranian EEZ, during the 2019-2020 fishing season. Of these, 112 were observed in Somali waters and 144 in Yemeni waters with what appears to be behavior consistent with fishing activity.

Map of the AIS tracks from 175 fishing vessels linked to Iran during the 2019-2020 fishing season. Significant activity can be seen inside the Somalia and Yemen EEZs.

Map of the AIS tracks from 175 fishing vessels linked to Iran during the 2019-2020 fishing season. Significant activity can be seen inside the Somalia and Yemen EEZs.

In addition, 93 AIS fishing net tracking buoys were also linked to Iran, these typically also transmit the vessel name and an identification number. By matching the names broadcast by the vessels and the fishing gear, 43 could be matched to vessels transmitting on AIS while 17 transmitted a vessel name that was not matched to their vessel’s AIS information. The remaining 33 vessels detected were not broadcasting a discernible name. The analysis indicates that the Iranian fleet operating in the Northwest Indian Ocean consists of at least 192 vessels.

The majority of distant water vessels from Iran and Pakistan use drifting gillnets to catch pelagic fish like tunas. Driftnets are not selective and can entangle protected species like sharks, turtles and manta rays. As a result the international community agreed through the UN to ban high seas drift gillnets longer than 2.5 km and a number of agreements, including in the Indian Ocean, have since been implemented.

At the request of the government of Somalia, who are clear that none of the identified vessels have been provided fishing licenses, we processed satellite optical imagery of the region, which offers the best visual “proof” of vessel activity and type and worked with the Norwegian satellite organization KSAT who provided further targeted analysis of their waters using Satellite Aperture Radar (SAR), which can identify large metal vessels and penetrate clouds. While the assessment found the number of Iranian vessels visible on AIS was already high, those figures are likely underestimated. Many targets identified in the satellite images do not correspond with an AIS signal, and the fleet appears to include both vessels using an AIS system and vessels without AIS, leading us to believe the actual number may be far higher.

A significant challenge to clear identification of the vessels and their authorization status is the lack of public and transparent information on authorized vessels by any of the indicated flag States in question. India, Iran, Pakistan and Sri Lanka do not publish lists of registered vessels, or of fishing authorisations. All four countries are contracting parties to the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, and as such are required to submit annually their lists of vessels authorised to target tuna and tuna-like species. However, there appear to be deliberate efforts to limit the information available on the individual vessels. For example, there are 1311 records for Iranian flagged vessels on the IOTC authorisation list; only 11 of these are identified by an individual vessel name. The remainder are only identified by the word ‘vessel’ and a number designation, for example “Vessel 1/1189”.

The lack of accurate, public vessel information makes it extremely difficult for other IOTC contracting parties, coastal States and the broader international community to be able to identify any vessels flying under the Iran, Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka flags, and to determine their authorization status – making enforcement efforts extremely complicated unless vessels are physically inspected and the authorization numbers or registration documents identified. This demonstrates a clear need to strengthen vessel identification requirements within IOTC and ensure contracting parties are providing up-to-date information on their vessels’ authorizations.

The region faces significant challenges to achieving effective ocean governance. Both Somalia and Yemen have had their maritime security capacity weakened by unrest and civil war, which makes their waters susceptible to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. Nonetheless, federal and regional governments in Somalia, working with the World Bank and Fish-i Africa, have made good progress in strengthening the licensing and monitoring of fishing activity in their waters and in combating piracy issues in the country. This progress risks being squandered without the strong action by flag States responsible for their fleet’s illegal activity in Somali waters and support from the international community.

While the IOTC is responsible for the management framework of tuna fishing in the region, enforcement relies on action by the flag State. All four flag States identified in the report are members of IOTC, however, there is no guarantee that measures will be taken against the vessels involved. We hope that our analysis will be used to advance enforcement efforts against these vessels by the flag states, improve vessel identification and authorization transparency, and gain support from international maritime security operations in the region to monitor and deter illegal fishing activity.

Charles Kilgour is the director of fisheries analysis at Global Fishing Watch. Duncan Copeland is the executive director of Trygg Mat Tracking.