Global Fishing Watch data helps researchers link shipping traffic to whale shark fatalities

The whale shark is the world’s largest fish, with adults weighing up to 5,000 pounds and reaching up to 20 meters in length. Earning the reputation of “gentle giant,” these massive creatures roam the tropical waters of the ocean, traveling long distances to find food to sustain their size.

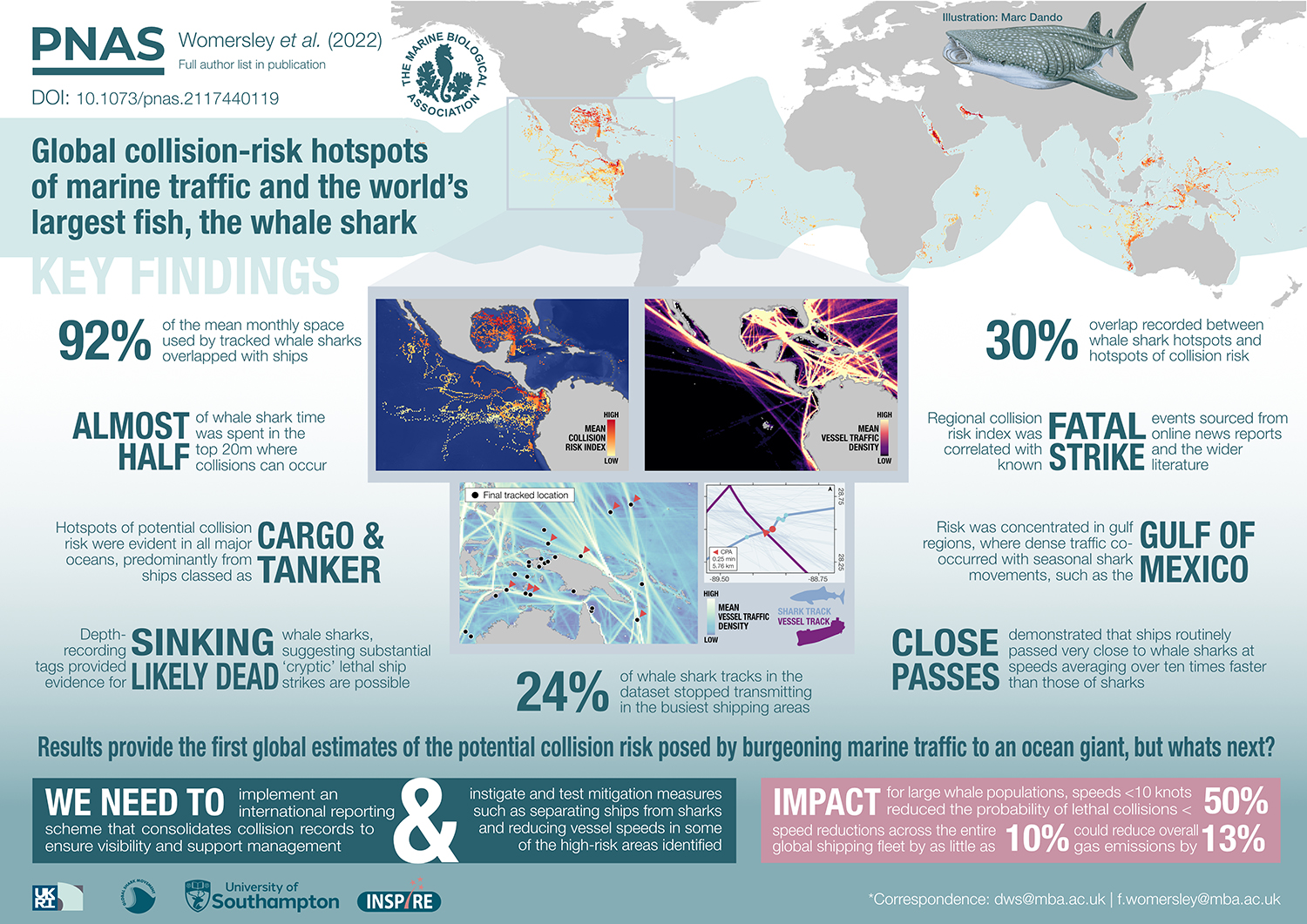

But whale shark numbers are in severe decline. Fishing and associated reef habitat degradation, entanglement in fishing gear and an increase in global shipping traffic have led to their status as an endangered species. Collisions with shipping vessels are assumed to be one of the most prominent threats faced by whale sharks, since they congregate in shallow waters in and around major shipping lanes. But lacking data on interactions between animal and machine, there has not been a practical way of monitoring this potential risk.

Freya Womersley, a post graduate researcher with the University of Southampton in the U.K., along with a team of scientists from more than 50 universities and research institutes, have done groundbreaking work to fill this information gap. The resulting paper, “Global collision-risk hotspots of marine traffic and the world’s largest fish, the whale shark,” was published May 9 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Three Global Fishing Watch scientists were co-authors of this study.

To determine how sharks and ships interact, the team of researchers—led by the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom and the University of Southampton—used satellite tracking technology to reveal the global overlap of whale sharks and shipping activity. For this study, automatic identification system (AIS) data provided by Global Fishing Watch and exactEarth was used to reveal the global footprint of shipping activity.

By mapping where sharks and ships shared waters, the research team discovered that over 90 percent of whale shark movements coincide with industrial shipping lanes. This is alarming because shipping vessels typically move 10 times faster than whale sharks, and the high level of proximity suggests a real risk of being hit by a ship for this endangered species. Collision risk was found across the global ocean, particularly in gulf regions where seasonal shark movements overlapped with heavy vessel traffic—tankers and cargo vessels specifically.

Researchers concluded that ship collisions with whale sharks may be significantly underestimated and recommended the implementation of an international, consolidated system for documenting these occurrences. The global merchant fleet has expanded dramatically in recent decades, and collision mitigation efforts like the team suggests are needed to reduce harm not just to whale sharks but numerous other species at risk.

The study is one of the first to apply Global Fishing Watch shipping activity datasets to a conservation challenge. Satellite technology is playing a key role in understanding and ultimately reversing the decline of marine populations around the world. From studies on wandering albatross populations potentially at risk from fishing hooks to research into as-yet unquantified fishing impacts to remote seamounts, Global Fishing Watch data is helping scientists around the world evaluate critical and often poorly understood human impacts to our ocean.

Tim White is a senior fisheries scientist at Global Fishing Watch.