New Global Fishing Watch technology merges nighttime images with GPS datasets to observe vessels not broadcasting their positions

When the sun sets, human activity on the ocean goes on. And every night, satellites snap a picture of all the activity taking place down below, including vessels at sea.

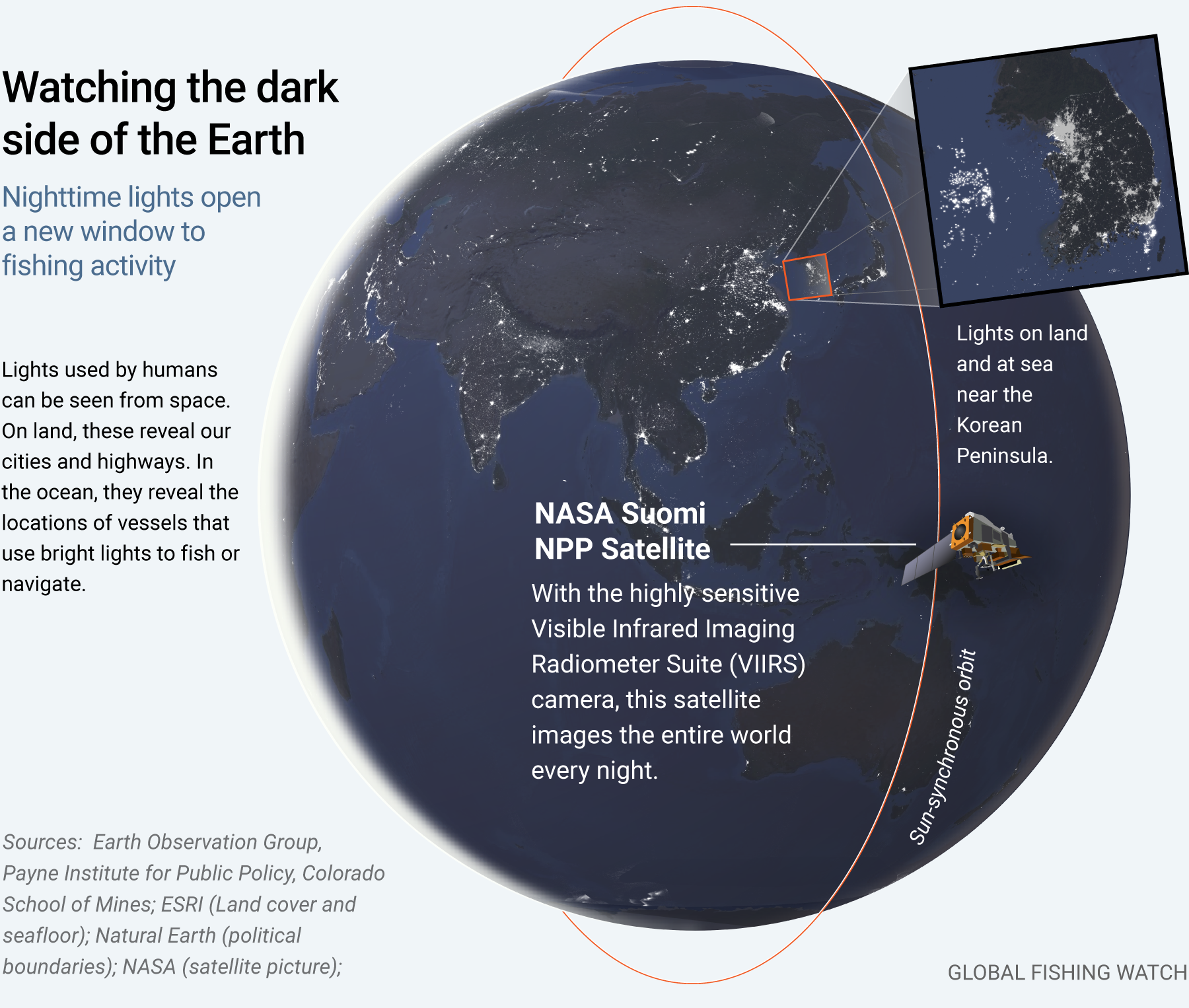

Vessels often are equipped with bright lights to illuminate the deck or surrounding ocean, allowing crew to carry out their work in the dark night hours. Some vessels, like squid and purse seine, use lights to attract catch to the surface. The satellites that monitor the earth work around the clock, making it possible for these boats to be seen from space. A NASA satellite, the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, carries an extremely sensitive camera, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), which images the entire earth’s surface every night.

Our research partners, Chris Elvidge and his team at the Earth Observation Group at Colorado School of Mines have compiled nighttime satellite imagery into a global database cataloging where these bright lights appear on the ocean. This database of lights has helped us reveal widespread illegal fishing in North Korea, track the squid fleet operating near the Galapagos, and reveal vessel activity globally.

Clues and challenges in the dark

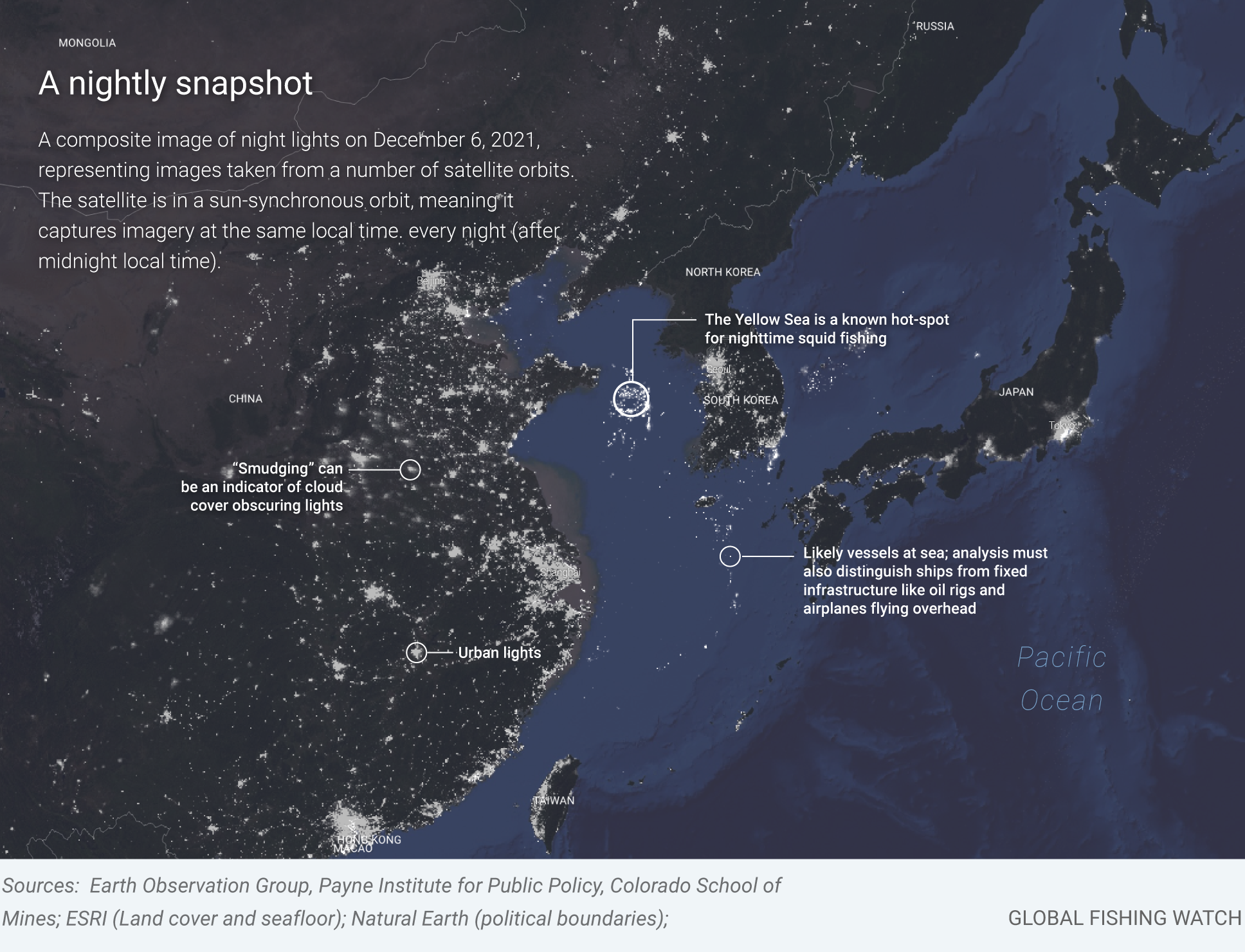

The VIIRS sensor detects lights at night, but it takes work to determine which lights are likely from vessels. One challenge is that the imagery is relatively low resolution–every pixel is 750 meters wide and contains enough room for more than one vessel. Clouds and reflected moonlight also limit our observations.

To further challenge our observations, the data only tells us if a vessel is present and how bright it is—without revealing the type of vessel or what it might be doing. To answer those questions, we turn to our massive dataset of vessel positions. Processed over the past decade, it includes more than 100 billion GPS positions broadcast from vessels over the automatic identification system (AIS), spanning more than 70,000 fishing vessels and a few hundred thousand non-fishing vessels.

Using a sophisticated matching system built on a method described in this paper, we have identified which of these lights correspond to vessels broadcasting their positions and which lights are not tracked by our systems. By combining the AIS data with vessels detected from night lights, we can reveal broader patterns of activity in the ocean. We can help identify which patches of light are fishing fleets and which are tankers or passenger vessels. And we can illuminate the activities of the “dark fleet” not broadcasting AIS.

A new layer of insight for map users

This matching is now available on the Global Fishing Watch map. Users can filter the VIIRS vessel detections based on the match to AIS and vessel type. Users can also filter by radiance. These tools allow us to explore the purposes of the different fleets of lights and identify fishing activity.

This matching process tells us what vessels we are seeing and gives us information to infer what the vessels that don’t match to AIS are doing. The matching process reveals that most of the very bright lights are fishing vessels.

Similarly, we can look at clusters of lights in different parts of the ocean. If we see a number of lights that match to fishing vessels, we can infer that the other nearby lights that don’t match to AIS are also fishing vessels. This is largely because fishing vessels group in similar locations to look for fish. Ensuring that we filter out any lights from shipping lanes, ports or oil platforms, we are able to identify patterns of night fishing and the true size of nighttime fishing fleets. We are now undertaking more detailed work to increase the accuracy of this modeling.

What the data can show us

This global dataset of vessel lights matched to AIS is the first of its kind, revealing incredible patterns of nighttime fishing activity. Out of 31.5 million detections of likely vessels in the VIIRS data, only slightly more than one-fifth were matched to vessels with AIS, meaning that on average, the number of vessels using lights is about five times greater than what is suggested by AIS data, giving us a sense of the incredible size of the “dark fleet.” The vast majority of these unmatched lights, over two-thirds, are in East and Southeast Asia. Of fishing vessels with AIS that match with VIIRS detection, just over 40 percent are squid jiggers.

Each region has a different story and shows variations in the type of fishing and non-fishing vessels using lights, and the fraction of vessels broadcasting AIS. From a regulatory perspective, there is a great need to quantify the locations and activities of these non-broadcasting vessels.

What the data can’t tell us

There are, of course, caveats in the data. We display the best match to a given detection, but, sometimes multiple nearby vessels could be detected as one. Overall, we find that of the 7.2 million night detections from 2017-2021 where we found a vessel match based on AIS tracks, over 80 percent had only one plausible vessel match. Future work will better quantify the uncertainty of some of these matches.

Our database of fishing and non-fishing vessels isn’t perfect, and there are many that are “unknown.” Also, many of the detections that are less bright may be false detections. Cosmic rays interact with the satellite sensor and create false detections of vessels. There is also the South Atlantic Anomaly–because of an anomaly in the earth’s magnetic field, cosmic rays are more common near South America and the southern Atlantic—resulting in more false detections in this part of the world. For this dataset, we have applied a filter that eliminates many of the detections in this region that might be cosmic rays, helping to reduce noise but also decreasing our ability to see real vessels in the region near South America.

Plotting all detections, especially those with weak radiance, also shows commercial airplanes and the aurora australis. Users who want to be more confident a light is a vessel should use only brighter detections (filter on the map to be brighter than 10 units of radaincenW/cm2/Sr).

This dataset matching VIIRS detections to AIS data is a first version. It is an important step toward a more complete quantification of human impacts to marine ecosystems. We will be working to increase its accuracy, better revealing activity across the global ocean.

Image Gallery: New light around the globe

A disabled AIS signal has been one way for potential unscrupulous operators to hide from oversight—and evidence points to a link between disabled or absent vessel signals and illegal activity. While AIS is not universally required and most “dark fleet” activity doesn’t break the law, it greatly needs to be quantified so we can better understand potential impacts to fisheries and ocean health. It is hard to protect what has not been mapped and measured. In the examples below, our new technique for matching lights to likely fishing events reveals activity we hadn’t before seen or quantified.

Previously unseen, intense fishing activity off southeast and east Asia

In East Asia and Southeast Asia, enormous fleets of fishing vessels use bright lights to attract their catch. When averaged across three years, it appears as if the entire ocean lights up.

In Europe, fishing with lights is much less common

Few fishing vessels use lights in Europe, while many non-fishing vessels—often passenger vessels—use lights when navigating shipping lanes. Fishing with lights is common, however, near Egypt, in the Adriatic Sea and near Turkey.

A truer estimate of squid fishing in the southeastern Pacific

This new system of matching AIS to night lights allows us to actually estimate the total fishing activity in the southeastern Pacific, especially the massive high seas squid fisheries. That is, we can estimate how many of the vessels are not broadcasting AIS. For the fleet operating outside the waters of Peru and around the Galapagos, about 70 percent of the vessel lights match to AIS, meaning 30 percent of the fleet is “dark.”

A vast “dark fleet” operates in the Indian Ocean

The high seas between the Arabian Peninsula and India hold a large squid fleet where the majority of vessels are not broadcasting AIS. We see some vessels crossing over the line and fishing in the waters of Oman–notably, these vessels are not broadcasting their AIS. The use of AIS by this squid fleet—very similar to the fleet operating near Peru and mostly Chinese—is only about 25 percent, meaning that the actual fishing activity of the fleet is about four times as great as what is suggested by our AIS data. In this region, we also see intense fishing activity along the west coast of India, almost entirely by vessels that don’t have AIS. © Global Fishing Watch

David Kroodsma is the director of research and innovation at Global Fishing Watch