Pacific case study suggests greater transparency will improve legitimacy and sustainability of tuna fisheries

Transshipment, the transfer of catch from fishing vessels to refrigerated cargo vessels (often called ‘reefers’ or ‘carriers’) is an important part of many seafood supply chains. But when transshipment occurs at sea, loopholes in governance and gaps in monitoring can obscure the origins and destinations of fish, and allow unscrupulous operators to launder catches. Transshipment has also been associated with other types of transnational crime, such as human trafficking, narcotics and wildlife smuggling, and money laundering.

A new study, Toward transparent governance of transboundary fisheries: The case of Pacific tuna transshipment, in the journal Marine Policy, analyzes Global Fishing Watch (GFW) data to explore how fisheries transparency and information sharing could support legitimate transshipment activities while ensuring effective conservation and management of transboundary fish stocks. Transboundary fisheries are complex resource systems involving multiple species and diverse actors across multiple jurisdictions. It takes intensive resources to manage transboundary fisheries, which is typically led by a regional fisheries management organization (RFMO).

Tuna fisheries are one of the most abundant and lucrative transboundary fisheries in the world. The study focused on the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, which is home to the largest tuna fishery, accounting for more than half the global tuna catches and estimated to be worth more than US$22 billion at final point of sale. The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) is charged with managing these fisheries, and is regarded as having robust policy practices.

When transshipment in the region is conducted by carrier vessels at designated ports and anchorages, or at sea within States’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs), they are subject to the rules and regulations of the port or coastal State in which it occurs. However, at-sea transshipment is often conducted on the high seas far from shore, with limited monitoring and oversight from authorities.

The WCPFC has adopted extensive management measures to ensure the sustainability of its fisheries and combat IUU fishing, including those related to transshipment. These measures call for 100% coverage by the WCPFC vessel monitoring system (VMS); 100% observer coverage on all purse seine fishing vessels; and 100% at-sea observer coverage for carrier vessels. It has also prohibited almost all at-sea transshipment by purse seine vessels.

Despite these measures, lack of regular oversight and formal data sharing arrangements result in a lack of transparency around transshipment practices for one of the most highly regulated and monitored transboundary fisheries in the world.

In the new Marine Policy study, an international team of researchers from the University of California, Santa Cruz, the International Monitoring Control and Surveillance Network, the University of Wollongong and GFW used publicly available automatic identification system (AIS) data to detect encounters at sea between purse seine vessels and carrier vessels. Their aim was to determine whether publicly available information is able to verify at-sea transshipments in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean in compliance with regional transshipment rules. Results suggested that even in one of the most regulated fisheries of the world, 68 percent of observed potential transshipments remain unsubstantiated.

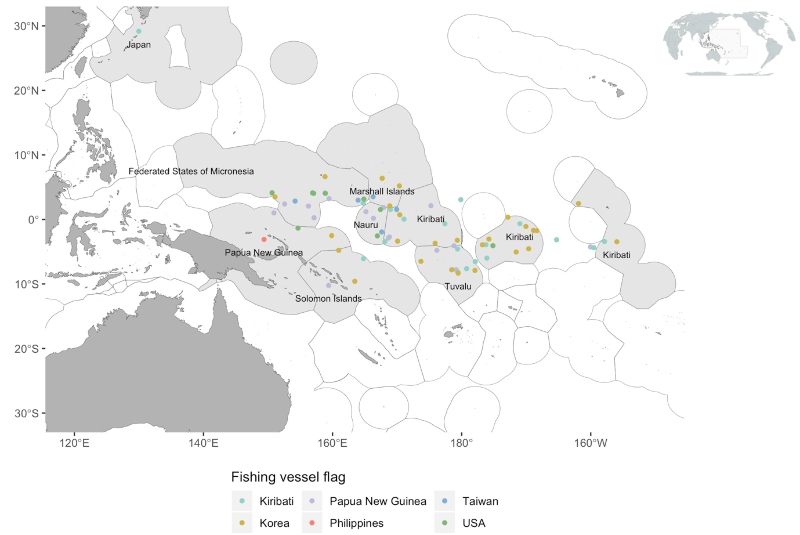

To target the primary tropical tuna fishing grounds, and omit other target species within the WCPO, the newly published study defined its scope as the WCPFC convention area between 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south latitude for the four years from 2014 to 2017. The researchers identified 77 potential transshipment encounters between 28 unique carrier vessels and 39 unique purse seine vessels within eight exclusive economic zones and on the high seas. Of the 77 encounters, 34 occurred in the waters of the eight Pacific Island countries that are Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). The EEZs of the PNA – comprising Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu – are some of the richest fishing grounds for the tropical purse seine tuna fishery.

Information from the PNA indicated that many of these potential transshipment encounters were not subject to observer coverage. The office of the PNA reviewed the encounters and, using observer reports, were able to verify that 25 of these encounters were not transshipments, but other activities such as provisioning and exchange of crew members. The remaining nine encounters identified using AIS data were not able to be verified using observer reports, possibly due to internal issues with validation or incomplete observer reports.

As AIS is not mandated for all carrier and fishing vessels, and can be subject to tampering, these figures are likely to be an underestimate of potential transshipment activity occurring in the WCPO. However, the authors concluded that increases in the number of detected encounters from year to year were likely due to improvements in AIS data quality over the period of the study. This suggests that AIS is becoming an increasingly powerful tool in improving public transparency and accountability, and supplementing the more guarded data collected by RFMOs from observer reports, transshipment declarations and VMS.

GFW’s carrier vessel portal layers several datasets to build a picture of carrier vessel activities. It combines AIS signals transmitted by carrier vessels with data from public vessel registries and machine learning techniques to provide greater information and insights on potential transshipment encounters and loitering events.

By focusing on carrier vessels, the carrier vessel portal complements GFW’s existing interactive public fishing vessel map, which allows users to track commercial fishing vessels in near-real time. Both the fishing vessel map and the portal are free to access by any member of the public. Regulators, policy makers and researchers can use the portal to pinpoint encounters between carrier and fishing vessels, analyze the vessels’ tracks and identify the ports that carrier vessels use and frequent.

The portal is a particularly powerful tool for regions that have extensive areas to monitor, such as the WCPO.

By using the portal, a fisheries official who has been notified that a given carrier vessel is headed their way will now be able to cross check and verify the vessel’s recent activity and its history of compliance elsewhere. This will enable the official to prioritize which vessels require further inspection, especially when they have limited inspection resources or capacity. Vessel operators can also use it to demonstrate their compliance with transshipment regulations.

By layering multiple sources of publicly available data, the authors of this study were able to build a picture of transshipment encounters in the WCPO. Access to this information will support governance in the region – information sharing can empower fisheries authorities to effectively govern transboundary fisheries, and close loopholes that have historically been exploited by those seeking to break the rules. Importantly, it also allows operators whose vessels operate within the comprehensive management framework across the region to demonstrate their compliance and strengthen traceability of their catches, solidifying the reputation of the region as leading in sustainable fisheries management.

Kamal Azmi is a senior research fellow at the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security at the University of Wollongong and a consultant for Global Fishing Watch. Katy Seto is an assistant professor in the Environmental Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz.