John Hocevar is the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA. His team has been using Global Fishing Watch to help focus their attention on specific areas within known hotspots of illegal activity. John is a co-author on a paper in the current issue of the journal Marine Policy that presents arguments for a moratorium on transshipment on the high seas. Among the issues raised in the paper is the association of transshipment with human trafficking and exploitation of workers who are trapped and abused on fishing vessels.

If you care about the ocean, you are probably familiar with the problem of pirate fishing. Known in wonkier circles as illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, pirate fishing catches somewhere between 11-26 million tons of fish per year and confounds efforts to sustainably manage fisheries. To put that in perspective, the weight of the entire human population of the state of California is roughly 3.5 million tons. As incredible as this figure is, the true impacts are almost certainly far worse, as it doesn’t fully account for the high rates of bycatch – of sharks, turtles, birds, and fish – that are thrown over the side dead and dying by these fisheries.

People are just starting to realize the scale of a closely related scandal regarding ill-treatment of workers on fishing boats. Shockingly, there are more people enslaved today than at any time in human history, and many are at sea. In interviews Greenpeace conducted with fishermen on Pacific longliners, people told us horror stories of being beaten, starved, and forced to work 18 hour days – often for months or even years at a time. Some reported being given so little food they had to eat bait to survive. Several had even witnessed a murder on board.

How are pirate fishing and slavery at sea connected?

We have caught and eaten most of the fish in the ocean. That has made it more difficult for fishing companies to be profitable, because they have to spend more time and fuel looking for fish. To cut costs, some unscrupulous operators are paying fishermen less – or even not at all. Even the most basic conveniences are denied these workers; we spoke to fishermen who had to pay to use the toilet. These inhumane and often illegal practices enable companies to keep more boats on the water, which further drives the overfishing that started the problem in the first place.

Shark finning is another example of how these issues are intertwined. Fishermen on many tuna boats are not paid a living wage, so they intentionally fish in a way that will catch a lot of sharks. They cut the fins off the sharks, often tossing the living bodies overboard to starve or be picked apart by fish and crabs once they sink to the bottom. The fishermen sell the fins for extra money, as they are (still!) highly valued for shark fin soup. The big tuna companies know this is happening, and it is a shameful part of the business model for those that do not ensure the fishermen supplying their tuna are paid enough to feed their families.

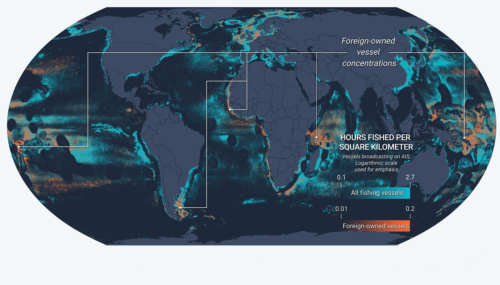

Many of the solutions to pirate fishing also address human rights abuses at sea. Increasing observer coverage and ending transshipment at sea are powerful means to protect workers as well as our oceans. With a commercial fleet of roughly 64,000 fishing boats operating in every corner of the globe, often hundreds or even thousands of miles from land, we need greater transparency in order to tackle these problems. Global Fishing Watch is playing a vital role in increasing supply chain traceability and improving monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS), which are fundamental parts of the answer. We have our work cut out for us, but it is finally possible to see a future ocean without either pirates or slaves.

[To read more about the global scope of transshipment, see the Global Fishing Watch transshipment report.]