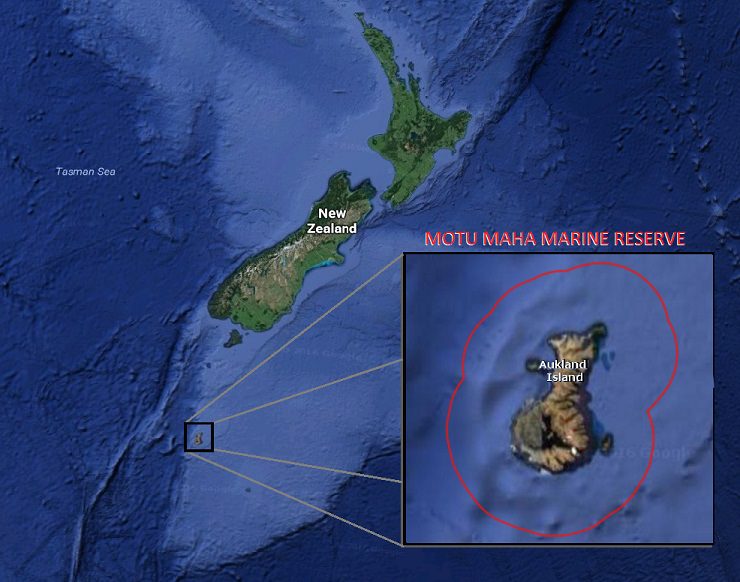

There were a whole lot of fishing vessels inside the Motu Maha no-take marine reserve last year, and every one of them had a reason to be there. As part of our series on deciphering suspicious behavior, we asked Dave Stevens, Senior Analyst for the New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries, to help us understand why nine fishing vessels made repeated trips into the 1,868 square mile marine reserve around the Auckland Islands—a World Heritage site 285 miles from the South Island of New Zealand.

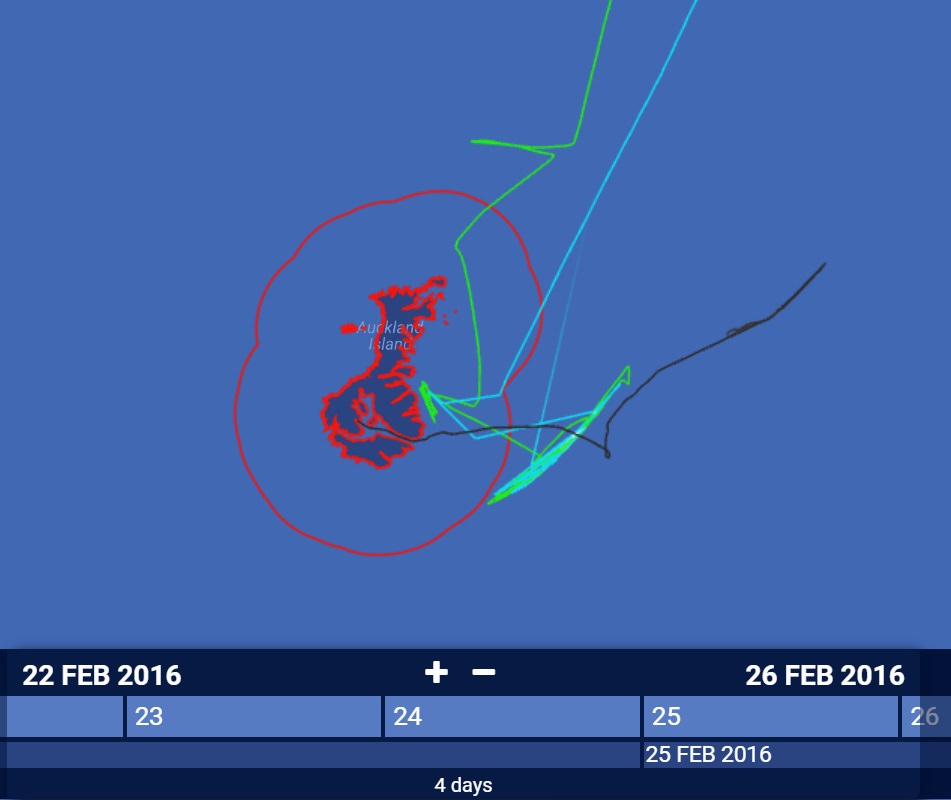

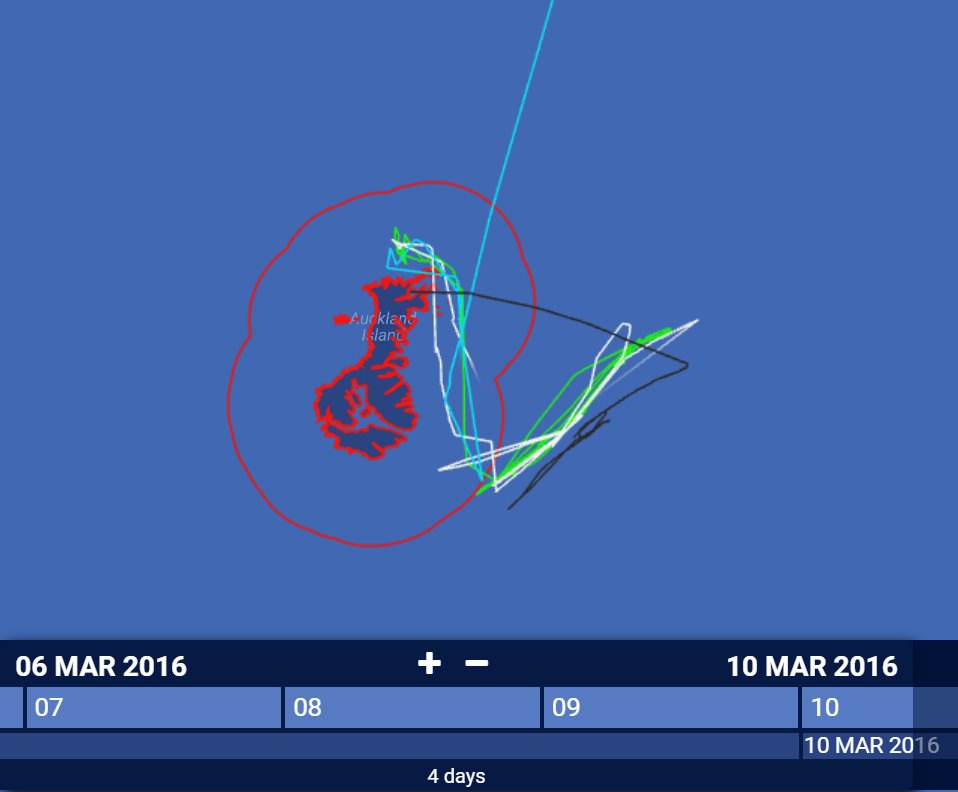

Not only did these nine vessels enter the reserve, but they often stayed there, moving back and forth for hours or even days at a time.

After analyzing the Global Fishing Watch map we sent him with all the tracks selected, Stevens determined that their speed, depth and area of activity are inconsistent with fishing. With that information, and records from the Ministry, he concluded that each of these vessels is either sheltering from wind and waves, seeking calm waters to transfer crew or equipment, or conducting research.

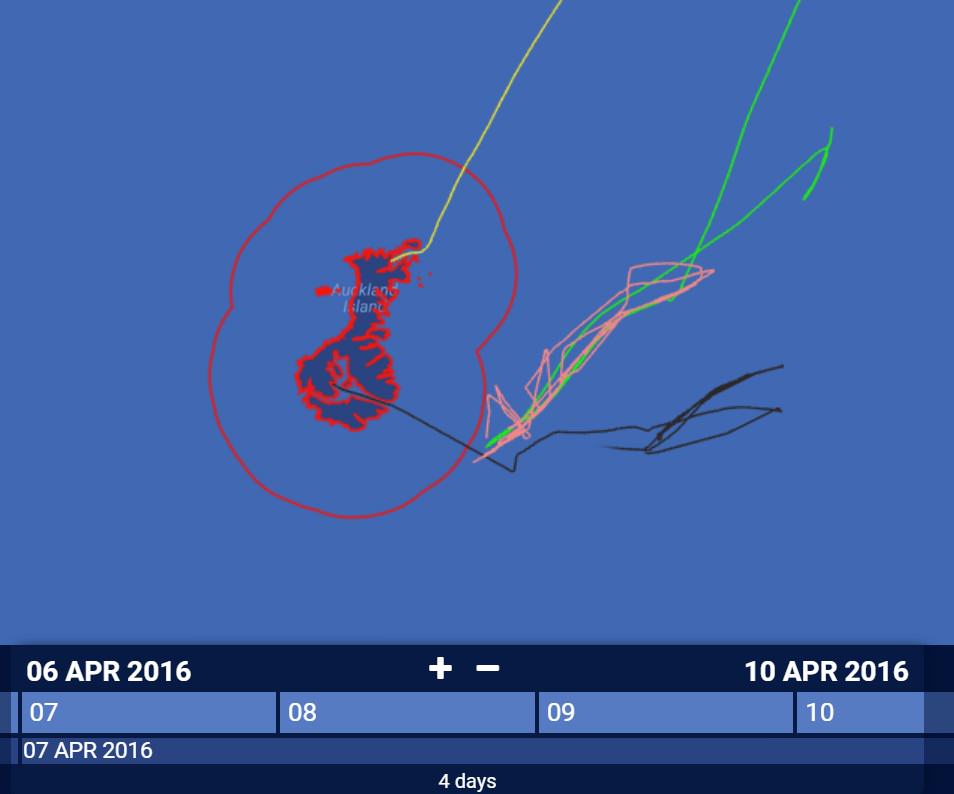

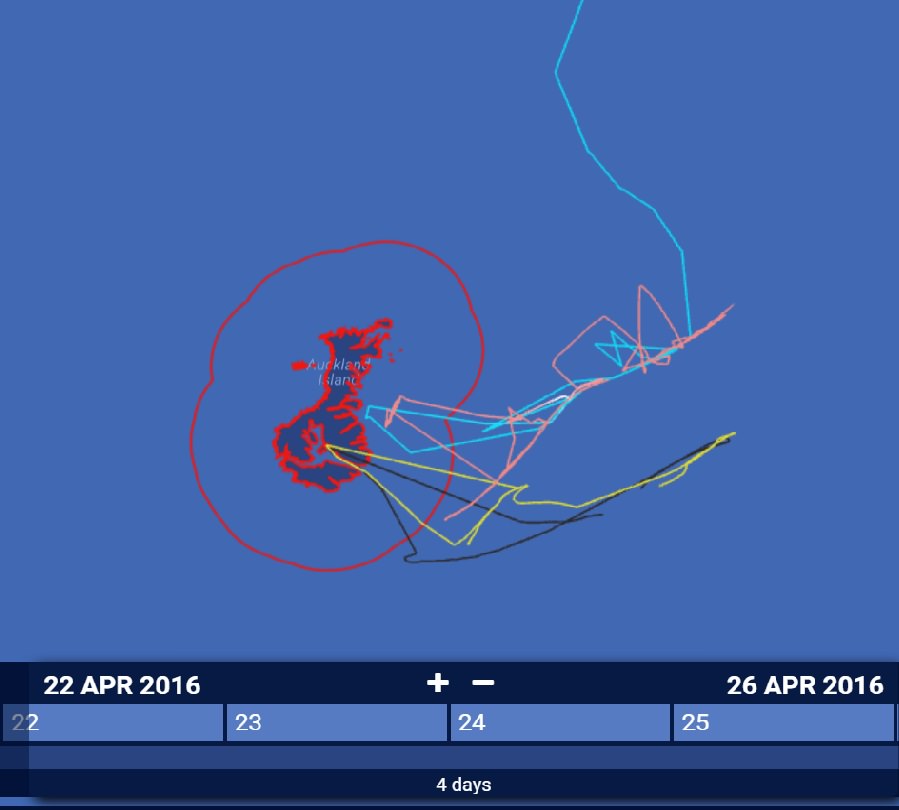

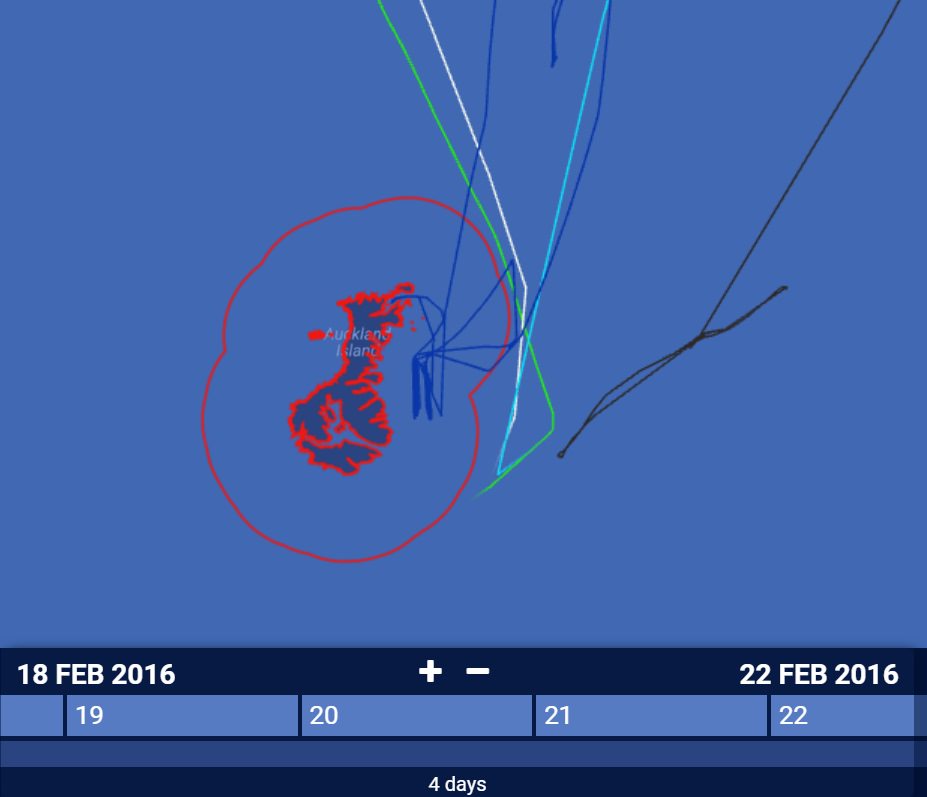

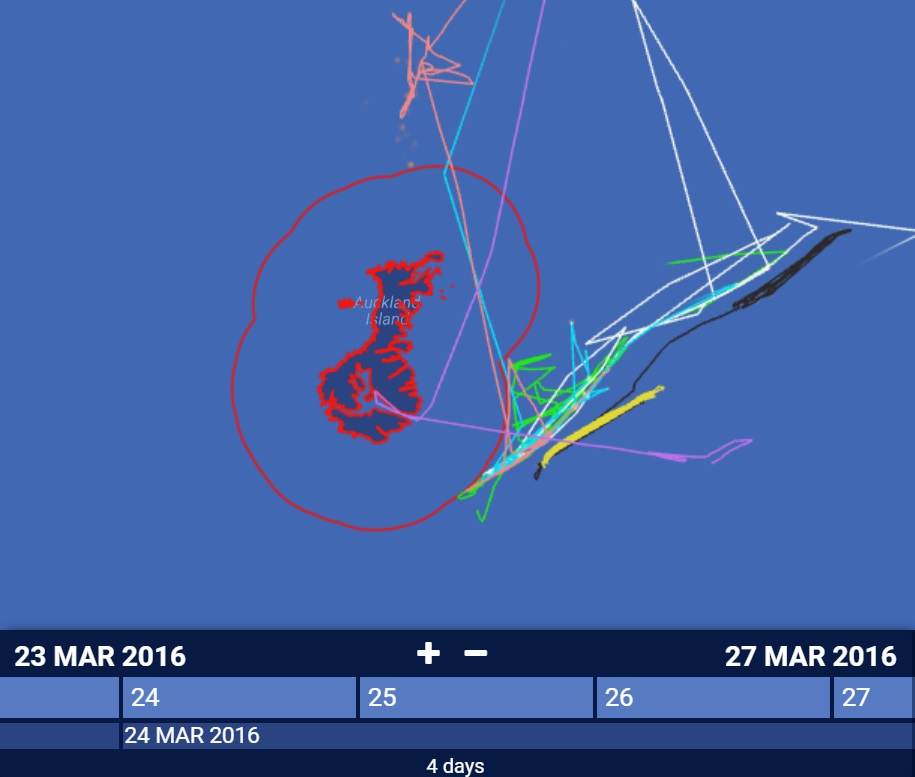

Considering the location, it all makes sense. The Auckland Islands are a cluster of subantarctic islands in the Southern Ocean, far from any other land. Along the northern and eastern edges of the marine protected area lie productive fishing grounds.

The islands offer the only wind break for miles and provide the only protection for a fishing boat faced with a storm. Prevailing winds in the region are from the West and Northwest, and the eastern side of the island is where the vessels repeatedly sought shelter. “When the vessels notify they are entering [the marine reserve] for the purpose of shelter, we check the wind map and any other notifications for the area to validate the vessels activity,” Stevens wrote in an email. “If they are going into the lee of these islands to transfer crew or equipment, then we check there is no fishing activity.”

Although there are no direct meteorological records for the Auckland Islands themselves, we checked historical weather data from stations in nearby regions of the Southern Ocean. It appears that data verify high winds and low-pressure conditions in the region during most vessel incursions. In addition, we saw multiple vessels heading directly for the same spot in the lee of the island at the same time.

Stevens also told us that although vessels are able to enter the marine reserve for sheltering they are not allowed to anchor. “This can account for vessel moving on what looks like fishing tracks,” he wrote.

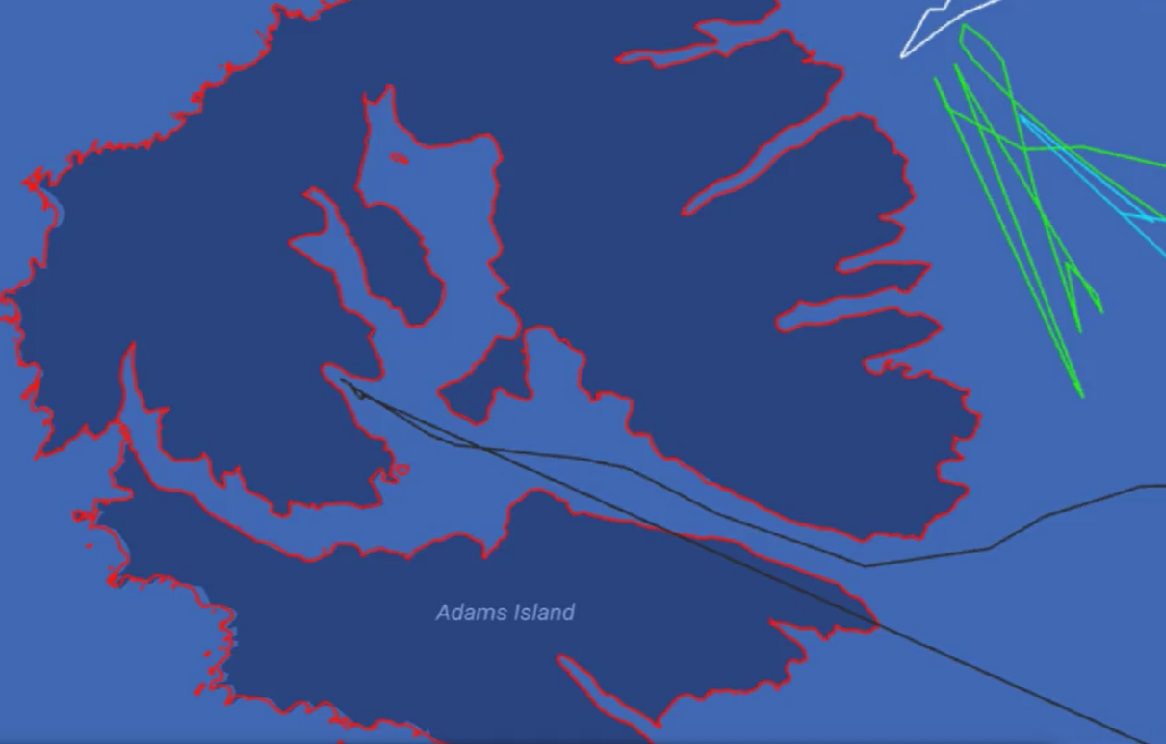

On both occasions the Drysdale enters the interior, tucking in between islands, while the Gom 379, Dongwon 701 and Dongwon 530 remain in open water near shore. This makes sense, because the Drysdale is a smaller boat. At only 25 meters she is more vulnerable to weather than the Donwong 530 at 57 meters, the Gom 379 at over 59 meters and the 81 meter long DongWon 701.

The impact of vessel size on behavior is even more apparent when weather sends the smaller vessels fleeing to shelter while larger vessels are able to withstand conditions on the high seas outside the MPA.

According to Stevens, one vessel, the Amaltal Explorer did enter the MPA, without reporting to authorities. “The vessel had not notified entry,” he wrote, but “several other vessels of similar size entered the Auckland Island territorial sea for shelter at the same time and similar area as Amaltal Explorer.”

Research

The tracks of two vessels repeatedly crossing into the Motu Maha MPA defy explanation by weather. According Stevens, both are research vessels:

The 70-meter Tangaroa (dark blue track) repeatedly enters the MPA and clearly traverses back and forth in what could easily look like fishing, while other vessels, including the much smaller Drysdale remain on the high seas.

The 28-meter Kaharoa (purple track) also travels into the marine protected area while similar sized vessels such as the Drysdale and the Albatross II remain on the fishing grounds.

Both the Kaharoa and the Tangaroa are part of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research fleet which conducts environmental research for New Zealand. As part of their expeditions, these vessels may catch fish for scientific purposes such as research into stock assessments and conservation, and they are licensed as Fishing Research Vessels (FRV) which appear in fishing vessel registries. Their tracks may show them fishing, taking water samples or conducting bottom surveys for geologic mapping and bathymetry.

In future posts, we’ll be speaking with research vessel operators to bring you some examples of the kind of activity Fishing Research Vessel tracks reveal.

In the meantime, take a look at our other posts that demonstrate the nuances of identifying fishing vessel activity from AIS tracks.