Experts from four countries joined forces to find out the real cause behind drastic decline in squid catch

A Global Fishing Watch-led study uncovers what is possibly the largest ever documented case of illegal fishing by vessels originating from one country operating in another nation’s waters, leading to significant ramifications. The story behind the research – how it was conceived and conducted – is testament to the power of collaboration and information sharing. This study required unprecedented international cooperation, engaging scientists from South Korea, Japan, Australia and the United States that used machine learning developed by Global Fishing Watch, as well as technology and data from multiple organizations. The study’s co-lead Jaeyoon Park says it will take similar multinational cooperation and data-sharing to achieve genuinely sustainable global fisheries.

For more than a decade now, fishers in Japan and South Korea alike have been increasingly alarmed by dramatic falls in their catches of squid – one of the region’s most popular seafood. Year after year, squid fishers in both countries have been reporting dwindling catch, to such an extent that recently their vessels have been left idle for longer and longer periods of the annual squid fishing season.

Sadly, we are becoming accustomed to alarming statistics on the collapse of fish stocks and biodiversity as a whole, but even so, the decline in squid throughout this region is astonishing. Since 2003 reported catches of the main target species, Pacific flying squid, have plummeted by 80 percent and 82 percent in South Korean and Japanese waters respectively. Fishers are reporting a decrease in the average size of squid being caught, indicating that fewer are reaching maturity. Media reports tell of communities that, for generations, had relied on squid fishing and are now facing the possible collapse of the industry.

While fishers and their families have watched their incomes plummet, academics are left puzzled over the most likely cause of this decline in catch. Many point to overfishing as the biggest culprit, while some suggest that climate change may be playing a part, with changes in water temperature affecting spawning and migration patterns. It seems to make depressing but all too familiar sense.

Unconvinced that all pieces of the puzzle are available to clearly explain the impact of human activity on the squid stock, fisheries expert and study co-lead Jungsam Lee of the Korea Maritime Institute began researching the alarming falls in squid catches. For years, Jungsam had been concerned by evidence that large numbers of fishing vessels originating from China were travelling north each season, allegedly to fish squid in North Korean waters.

While both South Korea and Japan have taken measures to reduce their fleets’ fishing pressure on squid, the absence of multilateral cooperation and information-sharing between all the countries involved in this transboundary fishery means it is impossible to get sound science and a regional management plan in place for the stock. The lack of data on China’s fishing activity meant a huge piece of the puzzle was missing – and ordinary Korean and Japanese fishers were literally paying the price.

Jungsam was convinced that this fishing pressure was impacting heavily on catches around the region. He expected that the UN sanctions (Resolutions 2371, 2375, and 2397) imposed on North Korea from the second half of 2017, which prohibited Pyongyang from selling or profiting from fishing rights to its waters, might ease the pressure and allow stocks to recover. Nonetheless, the overall catch in 2017 was another record low, and he suspected that many vessels continued fishing despite the sanctions.

It was in early 2018 that I met Jungsam in Busan, South Korea to discuss his theories about the squid vessels originating from China. Global Fishing Watch (GFW) had been seeking a real world application to test the increasingly sophisticated machine learning technologies it is deploying to track fishing activity globally. The declining catches in the squid fishery were just beginning to hit the headlines, but they had not caught my attention just yet. As a Korean myself, I was immediately interested in what Jungsam was telling us.

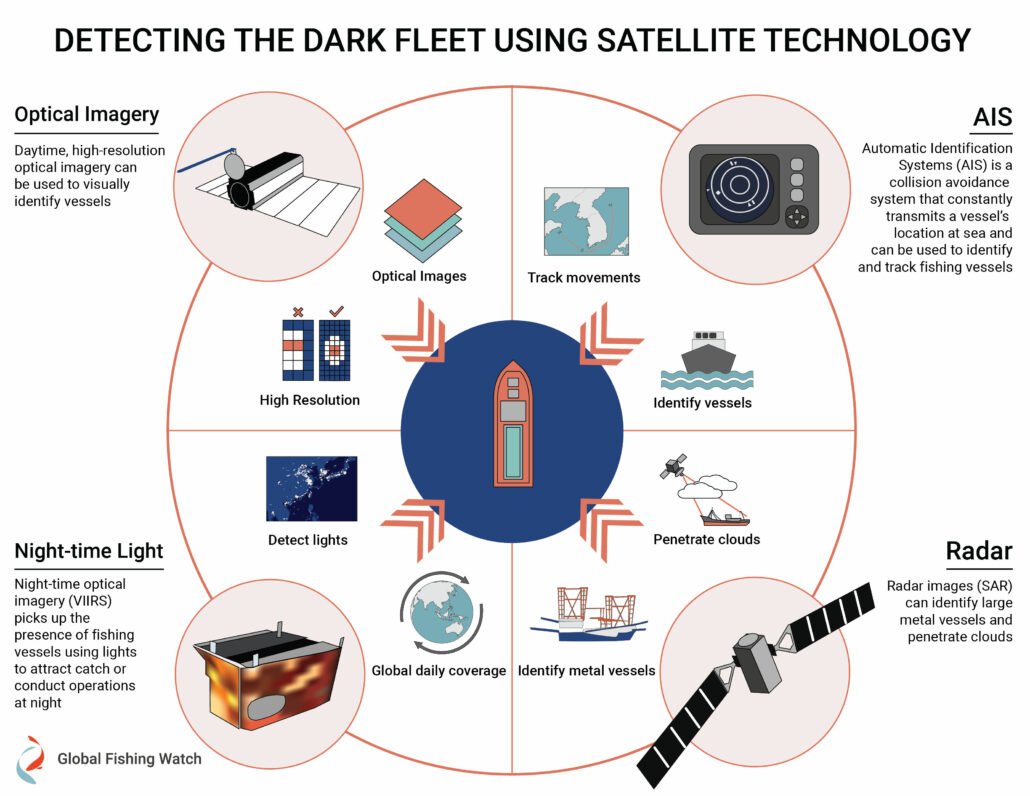

I looked through the dataset of these vessels’ automatic identification systems (AIS) transmissions — a collision avoidance system that constantly transmits a vessel’s location at sea. My suspicion was that many, if not all, were so-called “dark fleet” vessels – vessels that fail to show up in public vessel monitoring systems and are therefore said to operate in the dark. Often, these vessels are not officially or correctly registered to a country, and their haul goes unverified in any fisheries accounting. I realized this could be the test we were looking for: could GFW help shine a light on what these vessels were doing in North Korean waters? The idea for the study was born.

From the start, the research was all about collaboration and data-fusion. The team used four satellite technologies to illuminate the dark fleets harvesting Pacific flying squid in North Korean waters. This represented a new level of cooperation in the work GFW does, pulling in data and know-how from organizations as diverse as the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency and commercial satellite companies such as Planet. It was like piecing together a puzzle using different datasets layered over each other.

We obtained and analyzed high resolution images, together with data from radar and satellites that detect night-time lights, picking up the presence of squid fishing vessels that use lights to attract catch or conduct operations at night. These datasets were then cross-checked with available AIS data from vessels. This identified the vessels’ port of origin and destination as China. This, combined with regular checks of vessels passing through South Korean waters and observation of the same vessels operating in China’s waters, confirmed these were vessels originating from China. What we could not confirm, was if these vessels were authorized, or going rogue.

These four technologies have never before been combined to publicly expose the whereabouts and activities of dark fleets over consecutive years and across national waters. The scale of the activity revealed within a two-year time frame was shocking.

The pair trawlers, which represent the largest proportion of the detected vessels operating in these waters, covered immense areas of North Korea’s claimed exclusive economic zone, and, in the words of GFW’s research director and co-author of the report David Kroodsma, “They looked like they were mowing grass.” The trawlers haul a vast net between them, ploughing up and down the waters in row upon row. This type of fishing is so effective that it is tightly regulated in many countries, including South Korea.

Even as recent as a couple of years ago, we could not have seen this fishing activity in such detail, but advances in machine learning and the huge leap in high-resolution, high- frequency imagery enabled us to lift the veil on previously “invisible” fishing activity in this secretive region.

Combining estimations of the vessels’ fishing capacity and the time spent fishing, we calculated that these vessels likely caught as much squid as Japan and South Korea combined — more than 160,000 metric tons worth over US $440 million in 2017-2018. These calculations are conservative because we were unable to detect some vessels due to unfavorable conditions including cloudy weather and gaps in satellite coverage. Furthermore, the catch per vessel was estimated by comparing it to smaller South Korean vessels operating nearby.

The human cost

The study also identified another type of fishing that was taking place, one with chilling implications. For several years, increasing numbers of small North Korean wooden fishing boats have been washing up on Japanese and Russian coasts. According to media reports, some are empty – apparently abandoned – and some still have crew on board. Some contain a grim cargo of dead bodies, suspected to be fishers who have run out of fuel and water during their journeys. The numbers of these so-called “ghost boats” still remain high.

It is suspected that these small vessels originate from North Korean fishing villages, but there was no explanation for what was happening and why. Our study has almost certainly provided a missing link in this tragic mystery. The satellite optical data we analyzed shows about 3,000 small, wooden North Korean vessels, most of which fished illegally in Russian waters in 2018.

Evidence suggests that competition from the industrial trawlers is forcing North Korean fishers to go ever further afield in their search for fish. This has pushed them into neighboring Russian waters. For myself and Jungsam, as fellow Koreans, these are people who share the same culture and history as us. To see their desperate efforts to fish in boats so ill-equipped for this long-distance travel, knowing that they possibly face starvation and death, was extremely anguishing.

International cooperation

This study presents compelling evidence of human rights issues associated with the unmanaged status of much of this region’s squid fishery. Above and beyond the likely contravention of UN sanctions this fishing represents, our research highlights the fundamental failure in properly and transparently managing a shared resource.

Squid is a food product on which many countries and people in this region heavily rely. Just as this study depended on cooperation between organizations in many countries, so it makes clear the urgent need for cooperation between the countries involved in this fishery. We hope the data provided in this study will support future joint management efforts, and our work will demonstrate the power of collaboration. In addition, it is important to note that this technology can be scaled for use in other regions of the ocean where dark fleet fishing is suspected. China is certainly not alone in facing these challenges.

Experts like Jungsam, who have been dedicated to tackling issues that local legitimate fishers face for years, helped bring about this groundbreaking work. Building international partnerships, with local know-how, is a driving force for Global Fishing Watch and fundamental to advancing public knowledge about human activity at sea. While our expertise is different, our end goal is the same – making a world where honest fishers are recognized and rewarded, and illegal operators have nowhere to hide.

Jaeyoon Park is a senior data scientist at Global Fishing Watch.