Despite multiple requests from the Argentine Naval Prefecture to stop fishing, which included the firing of warning shots, HUA LI 8 fled into international waters. The vessel was detected days later attempting to enter the port of Montevideo in Uruguay. Once more the Argentine Naval force set out in pursuit of the HUA LI 8, and again the vessel fled.

Argentina requested support from INTERPOL, who issued a purple notice to alert member countries that the vessel remained at large.

Two months later, the Indonesian Navy arrested the HUA LI 8 in Belawan, North Sumatra.

An inspection of the vessel by Indonesian authorities determined the ship was carrying 102 tons of squid that had not been landed, which may have been illegal, unreported and unregulated catch. In addition, four of the 29 crew were Indonesian citizens that were later found to be victims of trafficking.

Though it is unclear what transpired on board the HUA LI 8, previous accounts from human trafficking victims in the fishing industry paint a picture of severely inhumane conditions. These may consist of physical violence, sleep deprivation, verbal abuse and death threats, withholding of pay and medical treatment, confiscation of personal identification, scarce or inadequate food and, in severe cases, even murder.

The HUA LI 8 was blacklisted from Argentinian waters due to violations of illegal fishing, trade and slavery. The owners of the vessel were forced to pay a fine of $175,800 USD (7 million ARS or 155,200 EUR) and the company was sanctioned by China.

The exploitation of crew on board the HUA LI 8 is not an isolated incident. Following an Associated Press exposé in 2015 that revealed the vast extent of forced labor and human rights abuses within the Thai fishing industry, further investigations disclosed that forced labor may be pervasive throughout the global fishing fleet – though the true extent remains unknown.

The International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations agency responsible for setting international labor standards, defines forced labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.” This definition encompasses vestiges of slavery or slave-like practices, various forms of debt bondage, and human trafficking.

The ILO estimates that 16 million people were victims of forced labor in 2016, with 11% of these in agriculture, forestry, or fisheries, and the Global Slavery Index published by the Minderoo Foundation reports that the seven countries with highest slavery risk in 2018 generated 39% of global fisheries catch. Although forced labor is frequently associated with countries that have low governance capacity, it is by no means exclusive to developing nations.

Click on the tracks to see other stories or scroll to continue.

In May of 2015, a Filipino fisherman on board the SOJIN 101, a fishing vessel flagged to the Republic of Korea, asked to be taken to a hospital to address his pericarditis - an inflammation of the lining around the heart. Reports show that the captain refused to return to port, not wanting to bear the cost of the time or fuel it would take to do so, and even accused the fisher of faking the illness to avoid work. Other crew reported that the captain frequently beat him as punishment for “faking illness.”

One month later, the fisher died. The captain reported the death to The Korea Coast Guard as a heart attack, and continued to operate the vessel. It was only after the SOJIN 101 made port in Busan that authorities were able to conduct an autopsy, finding evidence of an extreme infection in the membrane around the fishers heart indicating late stage, untreated pericarditis.

Shining a light on forced labor in fisheries

Despite the high publicity these atrocities receive once they’ve been exposed, more often than not, the abuses continue to go undetected. Authorities have limited resources, and offenders can easily disappear into the vastness of the ocean. So, how can we identify fishing vessels engaged in these abuses?

Case study reports and discussions with human rights practitioners suggest that vessels employing forced labor may behave fundamentally different from vessels that do not. Through interviews with a number of individuals working within this field, we identified 27 potential indicators of forced labor that can be observed using vessel monitoring data from satellites. These indicators are behaviors and characteristics that may indicate a vessel has a higher or lower risk of forced labor, which include activities like extended time at sea, avoidance of ports, and transshipment (the transfer of fish—or people—between vessels at sea).

By pairing these indicators with satellite data from 22 fishing vessels known or reported to use forced labor, we confirmed that vessels using forced labor behaved in detectably different ways from the rest of the global fishing fleet. The most important indicators identified were:

- Distance from port

- Vessel engine power

- Daily fishing hours

- Fishing hours in high seas

- Voyages per year

To answer previously unapproachable questions about the labor conditions in certain fisheries, we used machine learning along with Global Fishing Watch’s comprehensive database of satellite monitoring data to predict the risk of forced labor for 16,000 industrial longliner, squid jigger, and trawler fishing vessels in operation between 2012 and 2018.

How many vessels and victims could be affected by forced labor in fisheries?

We estimated that between 2,300 and 4,200 unique vessels were at high risk of using forced labor during at least one year from 2012-2018, representing about 14‑26% of the total vessels in the study. Our analyses suggest that collectively, these vessels had between 57,000-100,000 individuals on board, many of whom may have been victims of forced labor.

As the training dataset of positive vessels is based on a limited number of documented forced labour cases in the fisheries that have received the most attention, the sample is not random and may not fully represent the range of vessel types that use forced labour, resulting in sample selection bias.

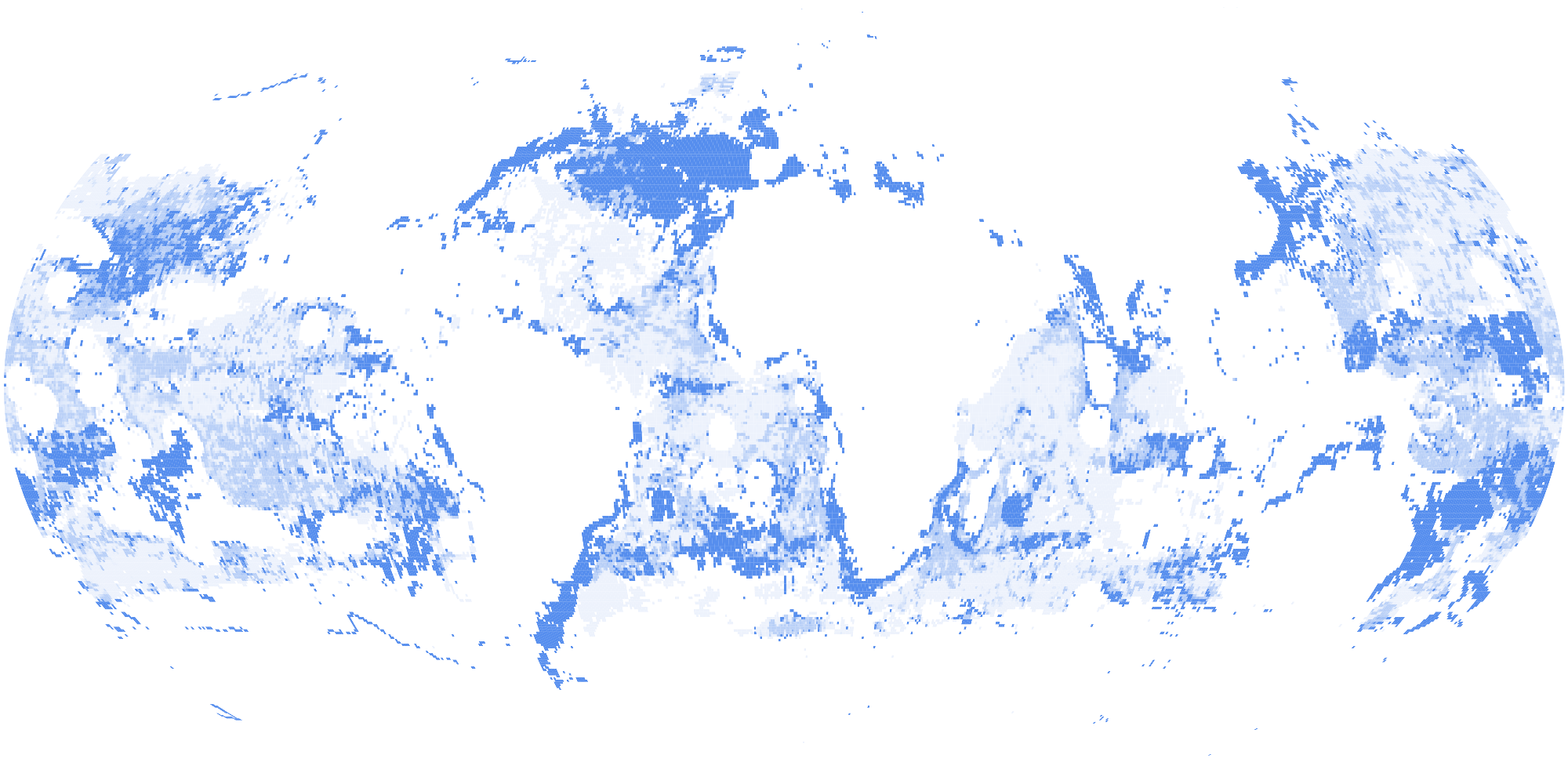

Where are these vessels fishing?

Forced labor is occurring in all major ocean basins, both on the high seas and within national jurisdictions. High-risk longliner activity is widespread geographically, with hotspots in the western Indian Ocean, the coasts off West Africa and South Africa, and the central Atlantic, an area that has not previously garnered much media attention in the context of forced labor and fisheries.

Meanwhile, the areas in the North Atlantic see high-risk trawling activity, and areas to the west and southeast of South America, in the northwestern Pacific and in the northern Indian Ocean are hotspots for high-risk squid jiggers.

What ports do they visit?

We also found that high-risk vessels visited ports across 79 developed and developing countries in 2018, including 39 Parties to the Port State Measures Agreement—a binding international agreement of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations designed to specifically target illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. These ports are predominantly found in Asia, Africa, and South America, although are occasionally found in North America, the Pacific and Europe. The ports represent both potential sources of exploited labor as well as transfer points for seafood caught using forced labor.

Recommendations

This study demonstrates that satellite data and machine learning can be used to identify the risk of forced labor in fisheries. For the model to inform targeted labor-based vessel inspections at port, we need more vessel and inspection data. We would be pleased to hear from any government, enforcement agency or industry group interested in collaborating with us to develop and improve the model to work towards eradicating forced labor in the fisheries sector.

We encourage flag States to ratify the ILO Work in Fishing Convention (C188), and require the use of mandatory vessel identification numbers, tracking systems (automatic identification systems or vessel monitoring systems) and monitoring of transshipment between fishing vessels and carrier (or reefer) vessels at sea. This would mean that vessels are unable to change their identity, operate in unknown locations or transfer seafood catch or fishers without monitoring. It would also deter those seeking to exploit the rules for financial gain and make it easier to identify, sanction and stop them when abuses occur. We urge flag States to make vessel identification, authorization and tracking data publicly available. This would support port, coastal States, and States that provide fishers and other stakeholders in their efforts to ensure compliance with relevant regulations.

We also encourage port States to ratify the ILO C188, as they are then able to apply the provisions to foreign-vessels landing catch in their ports, even where the flag State of that vessel has not ratified themselves.

Several major U.S. food sellers and pet food companies that were previously linked with fish caught by vessels engaged in forced labor have condemned labor abuses and vowed to take steps to prevent it from entering their supply chains. Information about the risk of forced labor in the supply chain at sea empowers these businesses to employ interventions within the seafood industry. Seafood suppliers and distributors could perform targeted due diligence within their supply chains, adding a new piece of available information to existing supply chain due diligence tools, and tracking and tracing the entire chain back to fishing vessel level.

Few victims of trafficking and forced labor in the fishing industry receive justice, and there is little doubt that the practice continues to go on undetected today. By using a forced labor risk model to inform targeted labor-based vessel inspections at port, working conditions aboard fishing vessels could be identified as unacceptable, and practitioners could even work towards the eradication of forced labor practices in the fisheries sector. To do that, we need more vessel and inspection data. We would be pleased to hear from any government, enforcement agency or industry group interested in collaborating with us on further development of the model.