Oceana’s Vice President for the United States and Global Fishing Watch, Jackie Savitz, has spent her career on the front lines of the fight to protect and save the world’s oceans. After earning her master’s degree in environmental science from the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory at the University of Maryland, Jackie moved into the advocacy and policy arena where she has led campaigns to address issues such as pollution, climate change, coastal development and offshore drilling. Versed in both policy and science, she has been the Executive Director of Coast Alliance, a policy analyst with the Environmental Working Group in Washington, D.C., and a scientist at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Jackie has been an instrumental leader in establishing the Global Fishing Watch partnership between Oceana, SkyTruth and Google.

What is your personal connection with the ocean?

I grew up spending my summers at the beach in New Jersey, at my grandparents place. We basically went to the beach the day school ended and came back the day it started. I fell in love with the oceans there, and by the time I was 12, I knew I wanted to be a marine biologist.

So I went to the University of Miami for my undergraduate degree in marine biology, and then to the University of Maryland for grad school. I knew I wanted to do applied work, and they were doing a lot of applied research on Chesapeake Bay pollution and fisheries issues. I was really concerned about the effects of pollution on marine animals. My work focused on the impacts of pesticides on copepods which form the base of the aquatic food chain.

How did you transition to advocacy?

I realized that research was very slow moving, and you had to study a very narrow question. I wanted to spend my time trying to make change, not just trying to do science. Many scientists I knew were purists and believed scientists should do just science and let the politicians make the decisions. But what I came to realize pretty quickly is, it’s not just about explaining to politicians why the science argues for addressing climate change or why it argues for stopping overfishing. Policy change is about more than just communicating science. There really is a role to play for scientist who are advocates and try to facilitate policy change, and for me, I knew that it was the right thing to do.

What are some of the campaigns that you’ve worked on that were most inspiring to you?

Global Fishing Watch really has been incredibly exciting work. But putting aside Global Fishing Watch, we recently were able to stop offshore drilling off the Atlantic Coast.

There had been two long term moratoria on offshore drilling in the Atlantic that were lifted during George W. Bush’s last year as president. When they were lifted, all of a sudden, it was open season on offshore drilling in the Atlantic. None of the conservation groups were that ready to take it on. They told us that trying to put a moratorium back in place was fantasy.

Oceana started up a campaign which later grew to involve a lot of organizations and ultimately won a big victory last year. We now effectively have a five-year moratorium on offshore drilling in the Atlantic. It can be overturned by Congress, but it was put in place by President Obama, so it has to be a pretty serious congressional move to overturn it. That was a huge victory for us, and I’m really proud of it.

How did you go about achieving that?

There are various tools we can use in advocacy. We can do grass roots campaigns, advertising strategies, litigation, or we can just try to show the science. I felt strongly that a grassroots campaign was what would win this.

When President Obama came in, he proposed drilling off the Atlantic Coast south of New Jersey into Florida. It occurred to me that the reason there was no drilling in the Pacific and no drilling north of New Jersey was that there was so much opposition to it there, but nobody in the southeast Atlantic had ever opposed it. So, the feeling was that the area was fair game. I thought if we could create that opposition we would be able to stop it.

We were able to get resolutions passed in over 100 municipalities along the coast. They don’t create law, but they send a pretty clear message to the decision makers—which in this case was the president—that this is not something we want on our coast. We had something like a thousand businesses and business groups that signed up in opposition to offshore drilling. We had some governors and more than 100 members of congress all getting behind the campaign, and that was what won the day.

What do you think will be the best strategy to achieve sustainable fishing?

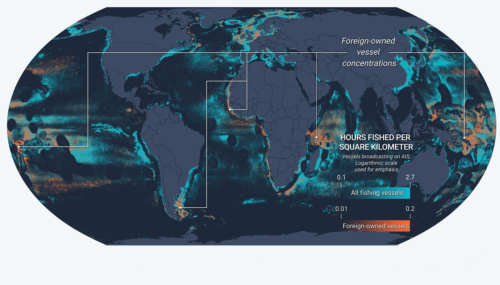

I think the key to getting sustainable fishing is going to be transparency, and we’ve taken a big step in the direction of transparency with Global Fishing Watch. We now have 35,000 of the world’s largest fishing vessels visible to everyone in the world on the internet for free, for the first time ever.

And while it’s a step in the right direction, there are still a lot of vessels that we aren’t seeing, either because they’re not required to use AIS at all, or they’re required to use it but they’ve turned it off, or because of the limitations of the technology.

So I think there’s still a lot more we need to do in order to improve transparency of fishing in our oceans, but I am glad we’ve taken this really big step.

What are some of the most important questions you would like to see people explore with this data?

I think it would be really great if we could get to a point where Global Fishing Watch can help us understand the full extent of fishing, and the full extent of the fish landings globally. There have been efforts to determine how much fish we’re getting, but we don’t really know for sure. For example FAO has come up with estimates, but others like Daniel Pauly’s lab and the Sea Around Us project have said those estimates are actually low. We need more certainty around that, and perhaps at some point Global Fishing Watch can give us a better read.

We’re not there yet at all, because we’re only seeing a fraction of the vessels, and we know that. But ultimately, we hope it can help us get a handle on how much fish we’re taking so we can better target fishery policies and optimize the amount of protein we’re getting out of the oceans without compromising the stability of fish populations.

I also hope that, over time, we’ll be able to see trends such as a reduction of illegal fishing. Or maybe we’ll see a dip, for instance, right around now after we launched Global Fishing Watch and people realize they should think more carefully doing illegal fishing. That’s the dream perhaps, but I do hope that over time, we’ll start to see trends and be able to track them.

I’m really hopeful that Global Fishing Watch will help us do all those kinds of things in the future and help us strengthen government enforcement programs. We’ve already been able to help in Kiribati, and we’ve had a number of governments approach us and ask us for that kind of help. So, if we can do that, if we can be A. a deterrent, B. a help to governments, and C. provide better information on what’s happening on our oceans, then that would be a pretty good outcome.

What gives you hope that we can solve the problems facing oceans today?

The emergence of technology gives me a lot of hope. It allows us to do things we could never have dreamed of doing before, and do it much more efficiently. The real beauty of Global Fishing Watch is that it allows us to use cloud computing and machine learning to mine massive data sets and pull out the important pieces. That’s something we could never do before. If we did it, we did it manually, and we were really only scratching the surface.

The story I like to tell is that one of our analysts, Maria José Cornax, who now directs our European Policy and Advocacy, used to track vessels point-by-point using real time data. She would plot where the vessel was and then wait an hour or so and plot where was is again. She invested a lot of time and a tremendous amount of work in tracking the position of one vessel in one place at one time, but she was able to point out that you can see a vessel create a footprint that shows it’s fishing. When Google let us know that they would have the ability to get historical AIS data, immediately I thought WOW, we could have a computer do what Maria Jose has been doing, only not just for one vessel at one time, but for all vessels, everywhere all the time. Then SkyTruth showed us that this was doable. They had created an early prototype that was very exciting, and that formed the basis for what we have today.

And that’s really the beauty of Global Fishing Watch. Any time we can automate an analysis like that, that’s really exciting to me. The partnership that we’ve developed between Oceana, SkyTruth and Google really optimizes the strengths of each of those organizations and is allowing us to make a big difference.