© DVIDS

The Issue

Just a few years ago, building a comprehensive picture of global fishing activity was impossible. Vast areas of the ocean were mostly unobserved—even today, they remained largely unmapped. Without being able to see what is taking place across the ocean, there has been little ability to manage it. This has allowed destructive fishing to occur on an unprecedented scale, threatening the health of the ocean and the sustainability of its extensive resources.

But a few years back, we spotted a possible solution.

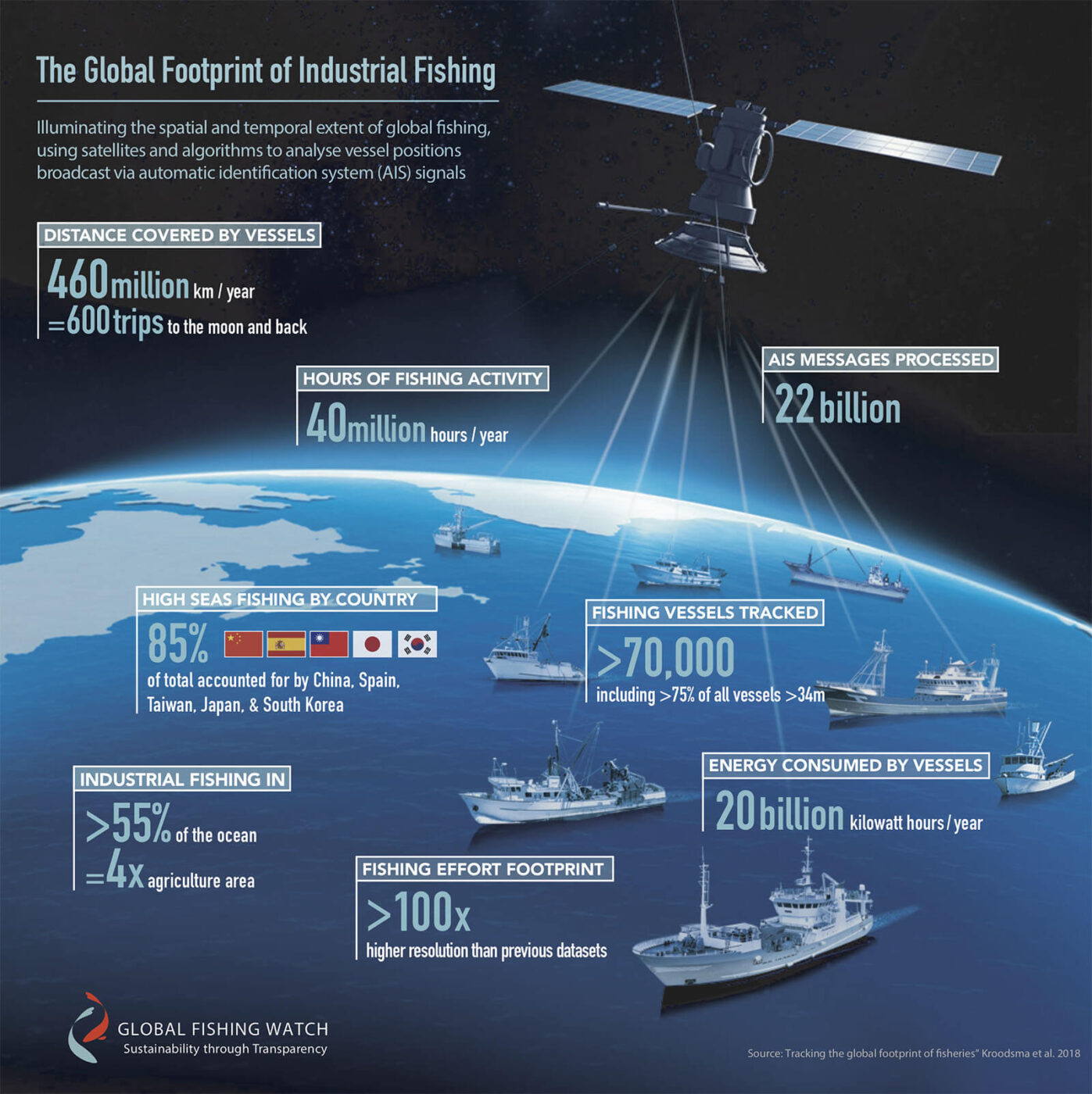

To avoid collisions at sea, large vessels are required under international law to broadcast their positions via something called automatic identification systems, or AIS. These transmission signals make vessels visible to other boats as they traverse the open waters. This tracking system became the basis of our approach in utilizing machine learning to publicly analyze AIS data to pinpoint fishing activity and better understand vessel movements.

Our Work

We processed 22 billion AIS messages and used them to track the movements of about 70,000 industrial fishing vessels from 2012-2016. Working with leading researchers, we employed this data to build the first global assessment of commercial fishing activity, which was published in Science in 2018.

By revealing the true extent of industrial fishing—an activity that occurs across 55 percent of the ocean and covers an area four times greater than all agricultural land—our research sparked debate on how to improve the way that fishing is both monitored and managed. Unleashing a wave of new research to better understand the quantification and impact of fishing activity, the study gained worldwide media attention and has been cited in hundreds of articles— and the open-source data that we released with it has been downloaded more than 6,000 times.

Since publication, we have added new data and new classifications to our model, allowing us to see more detail in vessel behavior. In 2021, we released an updated dataset spanning nearly a decade of fishing vessel activity from 2012-2019. And we won’t stop there. We will continue to refine our model to generate new and credible insights that allow us to better understand the true extent of fishing worldwide.

“I think most people will be surprised that until now, we didn’t really know where people were fishing in vast swaths of the ocean. This new data set will be instrumental in designing improved management of the world’s oceans that is good for the fish, ecosystems, and fishermen.”

Chris Costello,Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California Santa Barbara