Data advances understanding of global squid fishing fleets

New research harnesses power of data to illuminate expansion of squid fishing fleets into unregulated areas

Photo credit: AP Photo/Joshua Goodman

While illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing has been recognized as a global problem that threatens ocean ecosystems, sustainable fisheries and economic security, unregulated activity has received less attention.

Unregulated fishing occurs in areas where there are no applicable conservation or management measures, such as the high seas, and where fishing activities are carried out in a way that is not consistent with State responsibilities for marine resource conservation under international law.

Related Experts

Head of Applied Research

Unregulated fishing is subject to considerably less scrutiny than regulated activities, and is more likely to be associated with human rights violations and questionable labor practices.

Understanding factors that facilitate the increase and expansion of fishing efforts is important to be able to address the challenges of unregulated fishing as the demand for seafood products increases around the world.

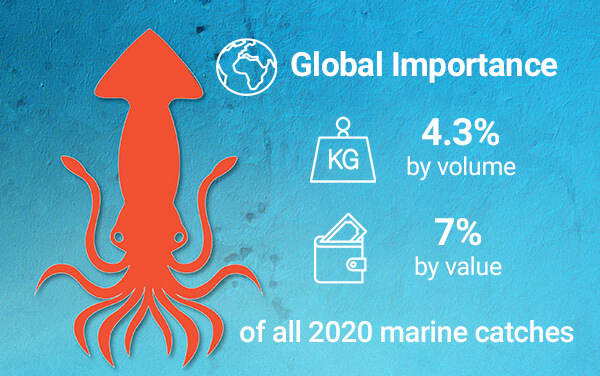

The squid fishery is of global importance–as of 2020, cephalopod catches constitute about 4.3 percent of all marine catches by volume and about 7 percent by value worldwide. Squid products are a staple in many cultures, including a number of Asian and Mediterranean countries, and provide important nutritional contributions to diets, particularly in light of declining finfish catches.

Squid are migratory, moving thousands of kilometers between coastal and offshore areas to feed and spawn, and the fishery often straddles multiple boundaries in regions including coastal States’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and the high seas.

Unregulated spaces are often directly adjacent to regulated ones—like EEZs. As squid populations move freely across those boundaries, coastal fishers in small artisanal boats often end up competing with larger vessels from distant water fleets.

This creates an equity imbalance for traditional and small-scale fishers who rely on species like squid that are targeted by industrial fleets, as well as for developing coastal States that depend on revenue from stocks that shift between regulated and unregulated areas.

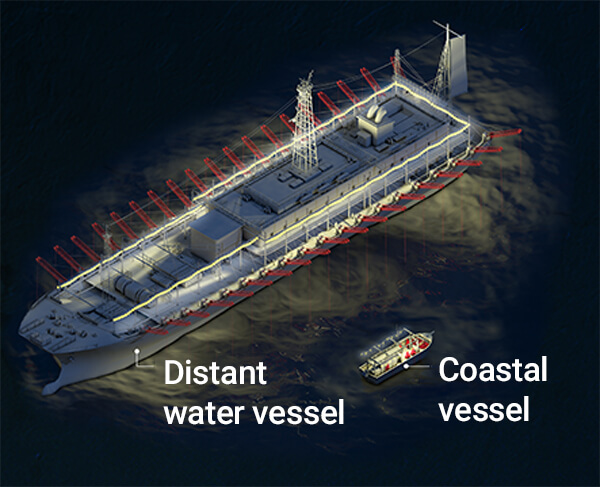

The industrial squid fishing fleets are highly mobile, with vessels moving globally between coastal areas and the high seas based on licensed fishing seasons and seasonal abundances and migratory patterns.

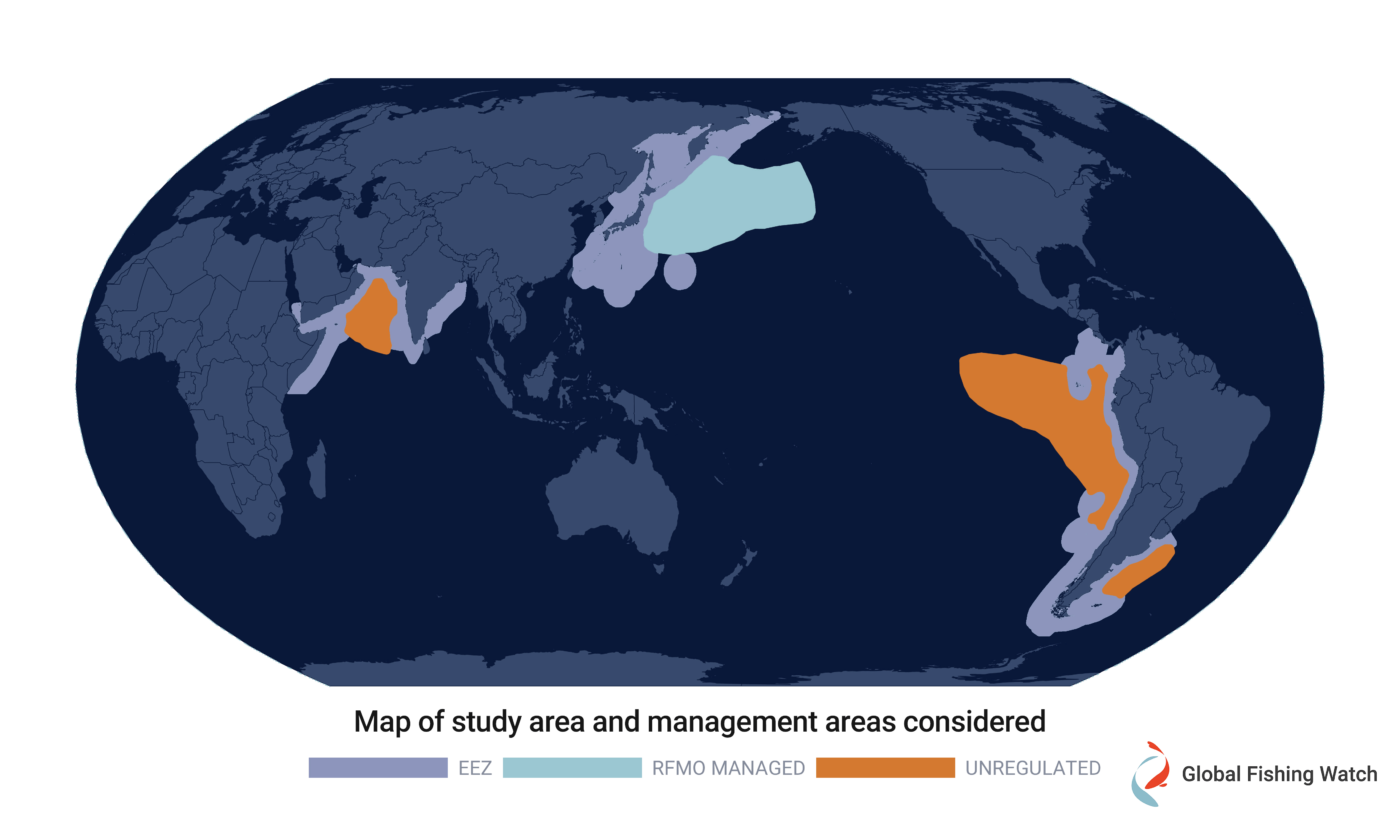

A patchwork of regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) serve to help manage fisheries on the high seas. These intergovernmental fisheries organizations are established by international agreements or treaties and can take different forms, but each share in managing and conserving fish stocks and marine ecosystems in a particular region.Currently, two RFMOs consider squid species within their mandates, both in the Pacific Ocean: the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC) and South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO).

In areas managed by a RFMO, fishing activities are considered unregulated when conducted by vessels without nationality, or by those flying a flag of a State or fishing entity that is not party to the RFMO in a manner that is inconsistent with the RFMO’s conservation measures.

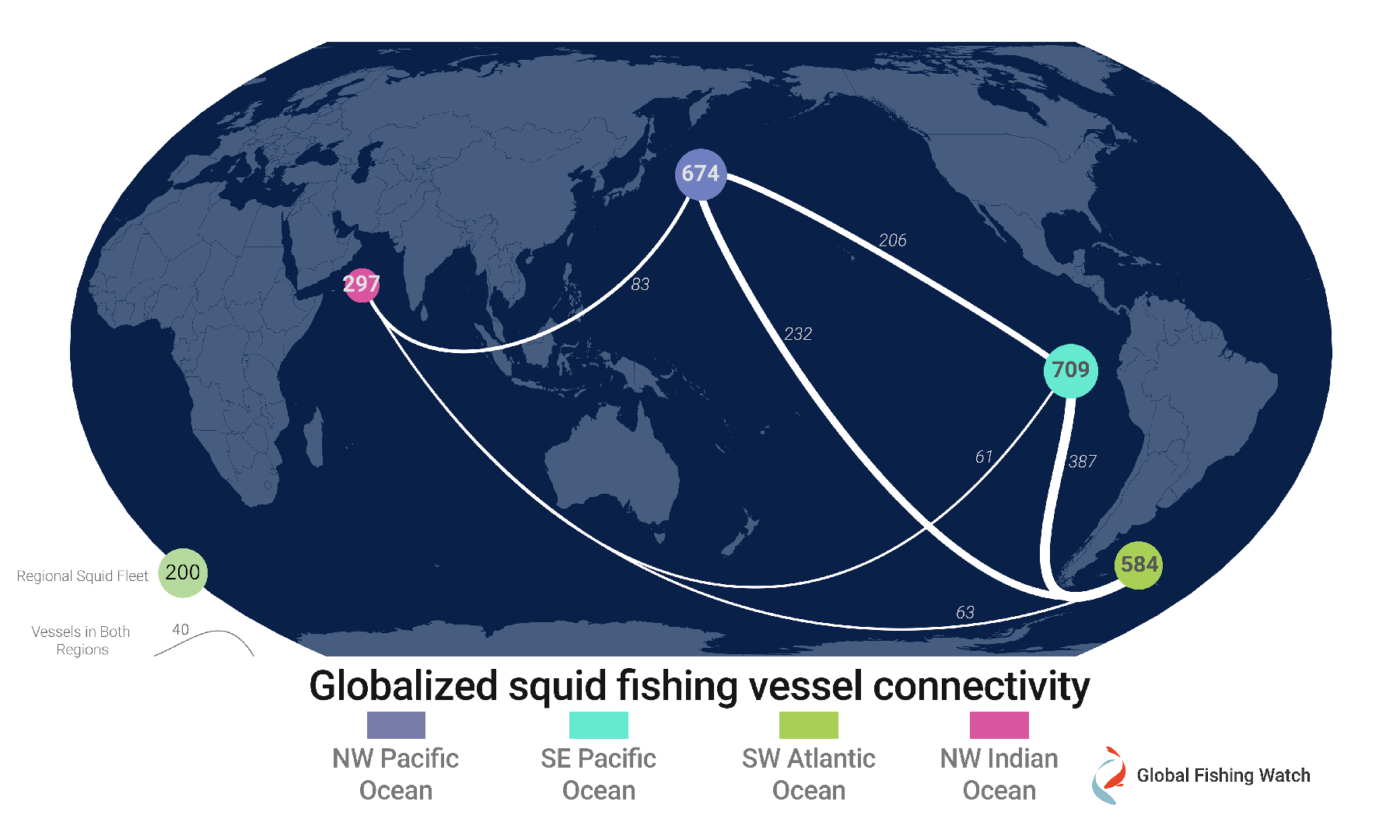

In an effort to better understand how the fisheries continue to grow and shift locations beyond the jurisdiction of management bodies, a new study explored global squid fisheries over a three-year period, from 2017 to 2020. It focused on four areas–the southwest Atlantic Ocean, northwest Indian Ocean, and the northwest and southeast Pacific Ocean–that contain both managed and unmanaged regions.

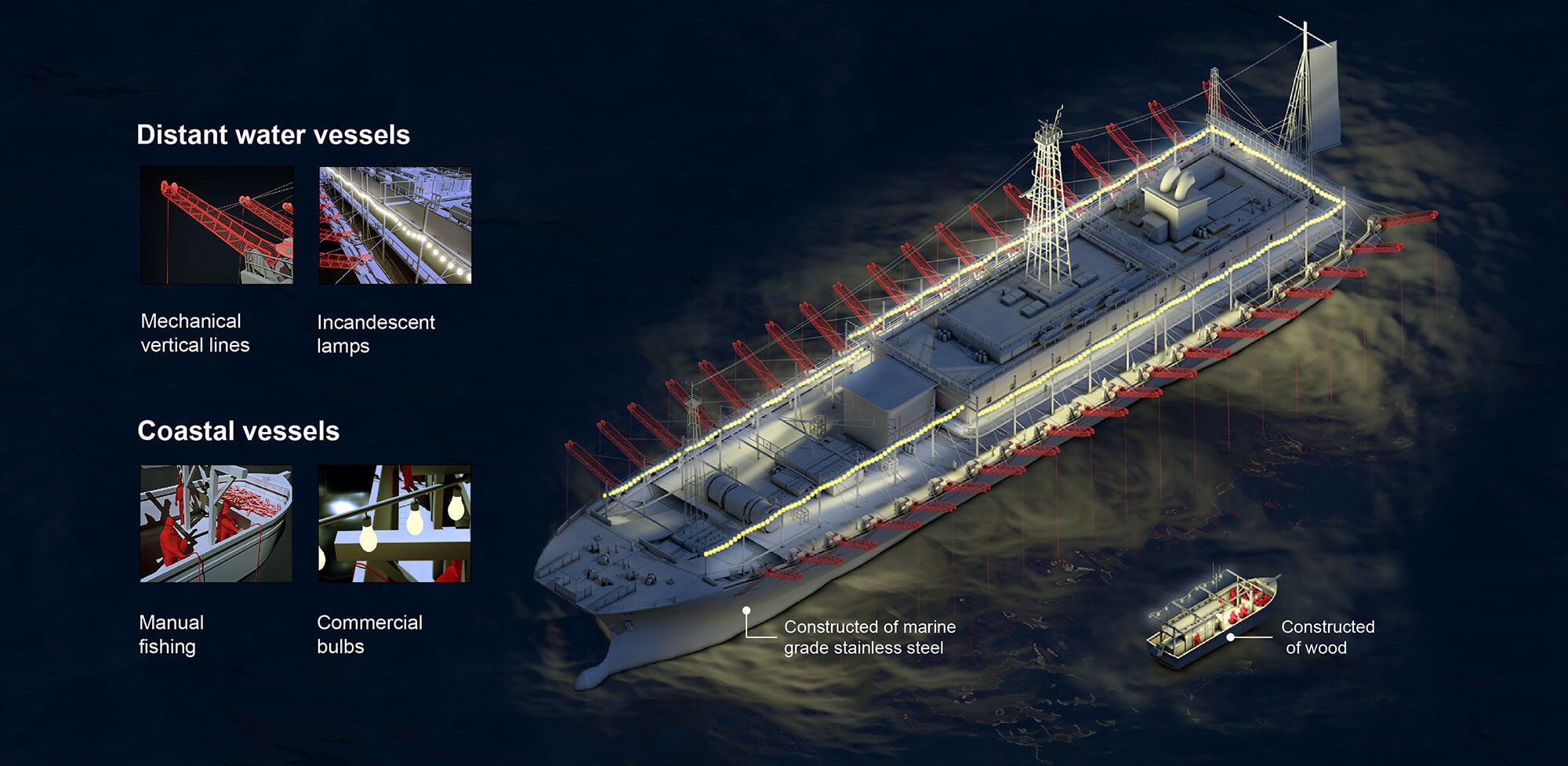

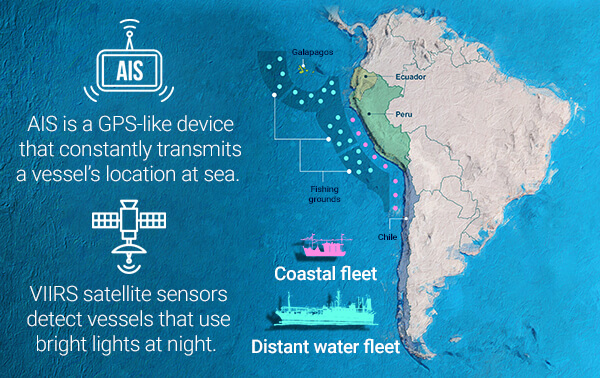

To determine which vessels were fishing where and when, activity was monitored by overlaying automatic information system (AIS) tracking data with visible infrared imaging radiometer suite (VIIRS) data. VIIRS can detect the array of bright lights squid vessels use to lure their catch to the surface–lights so intense that they are visible in satellite images of the Earth taken from space.

This activity was compared to areas covered by national and regional fisheries management bodies and squid regulations to determine how much fishing was happening in unregulated areas.

The analysis found that light-luring squid boats worked a combined 251,000 “vessel days” annually in 2020 across the globe. These units of effort track the number of days vessels are active in a region and net out to some 685 years’ worth of around-the-clock activity. Those numbers are up 68 percent from the 149,000 vessel days fished in 2017.

It also found that these squid fishing vessels fished largely (86 percent) in unregulated areas, equating to 4.4 million total hours of fishing time between 2017-2020. While unregulated fishing is not necessarily illegal, it presents challenges for fisheries sustainability and resource equity, and has been connected to questionable human rights and labor practices.

Annual total effort estimates were also calculated from VIIRS for each region. The estimates showed that fishing pressure in the northwest Indian Ocean and southwest Pacific Ocean—areas with no management of squid fishing—increased from 2017 to 2020 while fishing pressure in the northwest Pacific Ocean, where there is at least some oversight of the activity, remained static during that time. In particular, in the northwest Indian Ocean, fishing effort increased rapidly from 13,000 to 56,000 vessel days from 2017 to 2020, and the number of vessels working there jumped more than fourfold, from 57 to 250.

The graphs above represent vessel days estimated from VIIRS. The orange bar and the number in the bar represent the number and the percentage of the vessels detected only by VIIRS, respectively. The blue bar represents vessels detected by both VIIRS and AIS.

The data also showed how highly mobile the fleets are—more than half of those studied operated in multiple regions many times a year.

The majority of these boats belong to the distant-water fleets of major fishing nations. China’s distant-water fishing fleet accounted for most—1,123 of the 1,394 light-luring vessels examined—and accounted for 4 million hours of fishing, or 92 percent of all the fishing tracked. Other major squid fishing countries include the Republic of Korea, Chinese Taipei and Japan.

Overall, the analysis shows vessels freely moving between regulated and unregulated spaces, fishing large amounts of squid with little to no oversight or data reporting. This near-constant fishing puts added pressure on squid stocks, which experts believe is in decline, both globally and in each of the areas examined in the study.

Understanding that fleets may take advantage of fragmented regulations to maximize catch demonstrates the need for coordinated action for governments, companies and regulatory bodies to collectively take action to regulate squid fishing with intentional steps to increase communication and data sharing.

0%

China’s distant-water fishing fleet makes up 92 percent of all the fishing tracked in the study.