Along with the recent release of our fishing effort data, we are also releasing information on how good AIS coverage is for different parts of the world. That is, in some parts of the ocean, an AIS signal sent by a vessel is very likely to be in our database, and in others, it is less likely to be so.

Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals can be received by terrestrial antennas near the shore, and also by a constellation of satellites. A satellite can receive messages from vessels that are thousands of kilometers apart, and, in a crowded part of the world (such as southeast Asia), a single satellite receives messages from thousands of vessels. These messages can interfere with one another, and thus, in these regions of high vessel density, satellite AIS coverage is not as good as it is in low density parts of the world.

By contract, a terrestrial antenna can only receive messages from vessels a few dozen kilometers, at most, out to see. As such, they receive fewer messages at once, and have less of a problem with message interference. These antennas can be found along many of the world’s coastlines, especially in developed countries.

We have a database of AIS “coverage” that we will soon be making public, and which can be used to help interpret the regions of world (and time frames) that our data can be best used.

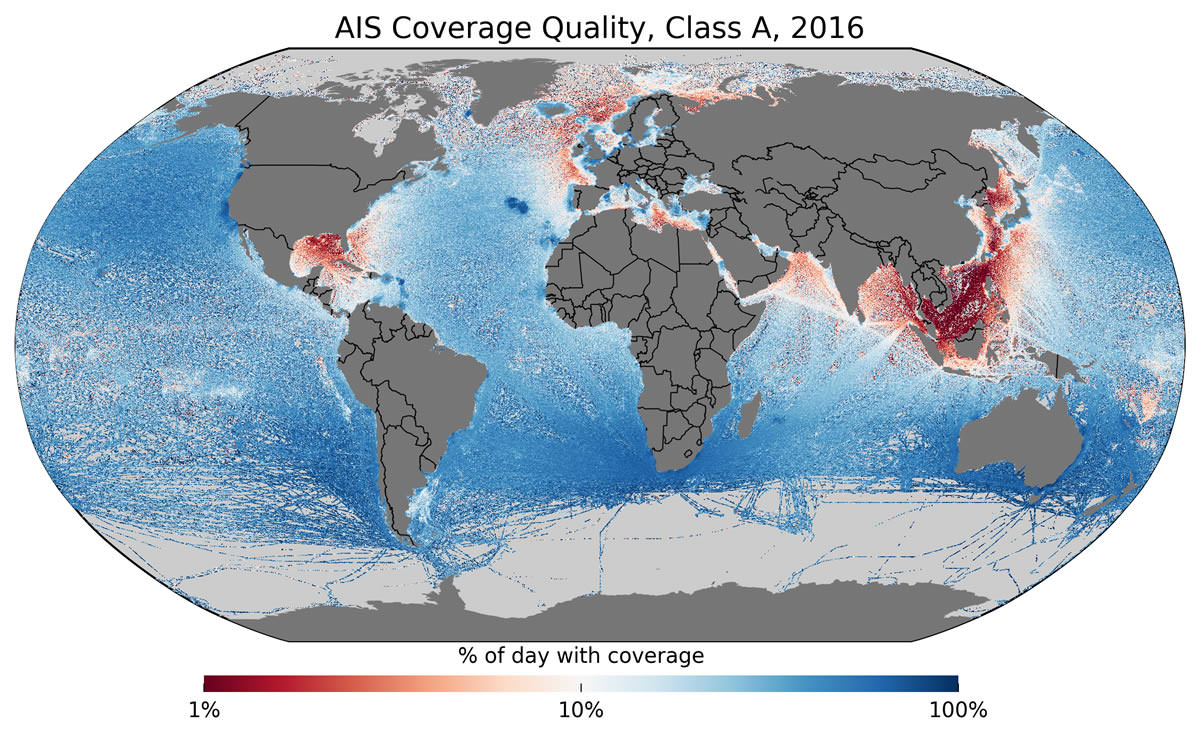

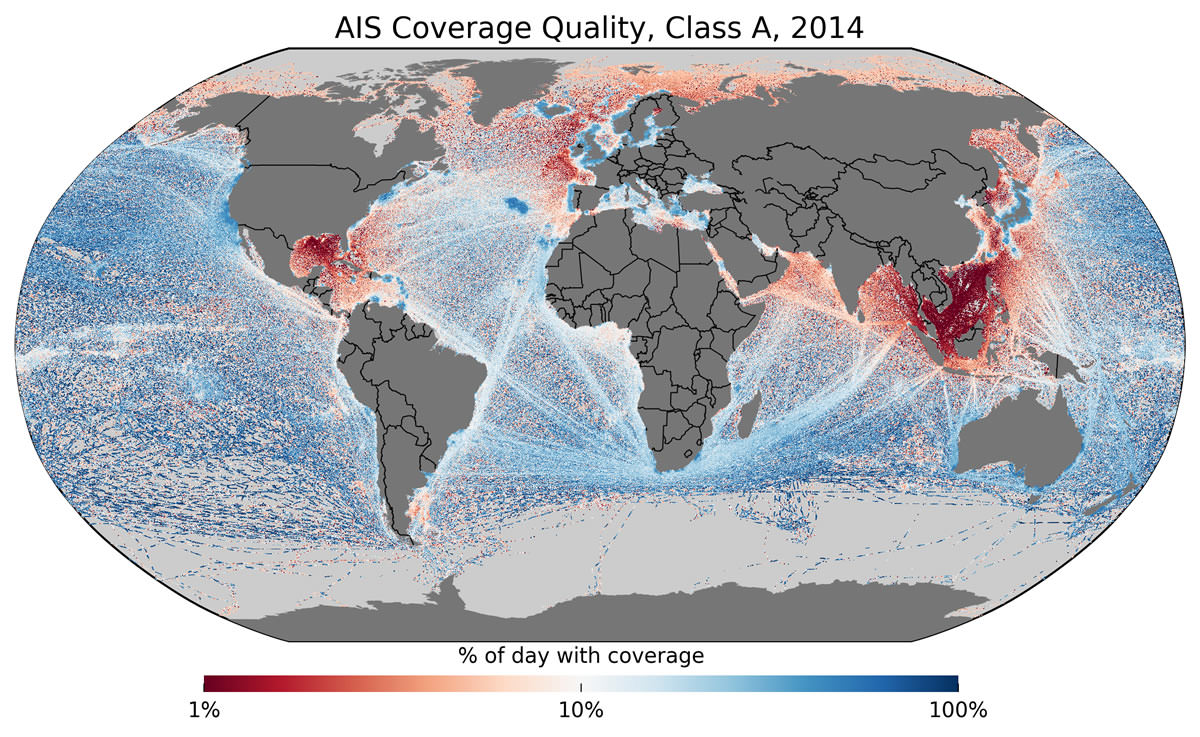

Below is an image of coverage quality for Class A AIS devices in 2016, and in 2014. What this map does is divide the day into five minute intervals, and then count the number of those five minute intervals in which we receive a message from a vessel. A hundred percent would be receiving a message every five minutes; one percent would mean that only about two signals in two different five minute periods were received. Our ability to measure fishing effort deteriorates rapidly below about 10 percent of the day, which translates into about 20 to 30 positions in a given day.